by James Delhauer

As vaccination rates continue to rise and COVID case numbers steadily decline here in the United States, it feels as though we have turned a corner in the pandemic. Life begins to resemble its old self. However, the effects of this global event continue to be felt.

Technological developments spearheaded by a need for a remote society are here to stay. We are more reliant than ever on communication tools. A record 2.26 billion internet-enabled devices were sold in 2020. All of these gizmos and gadgets require resources to manufacture and the pandemic has strained supply lines. This has resulted in a global shortage of semiconductor chips, integrated circuits used in the manufacturing of electronic devices. This chip shortage has resulted in limited availability of consumer electronics across the markets worldwide, leading to sharp price increases on goods. However, this might just be the beginning. As the current estimates foresee the shortage lasting until 2023, this shortage will have long-term consequences across every tech-reliant industry. The industries of film and television will be no exception.

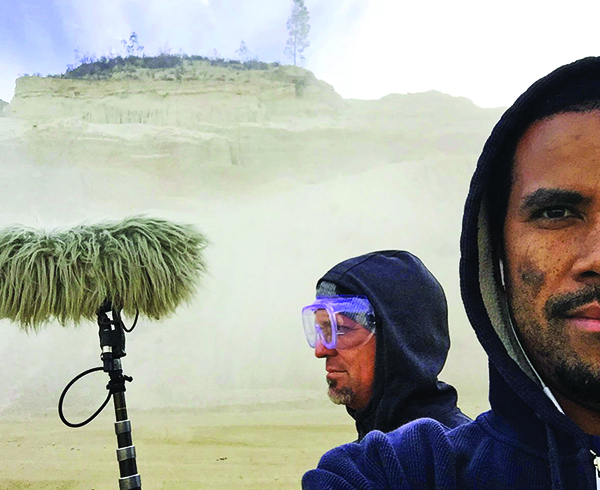

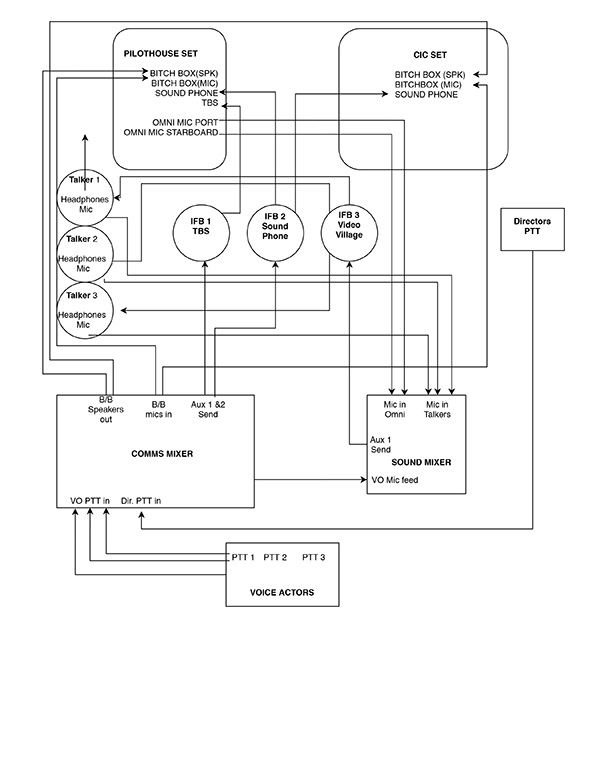

To understand this situation, some context is needed. Integrated circuits are complicated to manufacture. Specialized machinery is used to integrate components that would be far too small for the human hand to manipulate. This is a delicate task. The slightest contamination of dust is enough to disrupt the process. And so the machinery is housed in air-tight clean rooms and a conveyer system is used to pass components from clean room to clean room, so as to prevent any chance of contamination. This sort of assembly line is expensive to manufacture and it is common for semiconductor fabrication plant construction costs to reach four billion dollars. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s most valuable semiconductor company, estimates that its upcoming facility may reach costs of twenty billion.

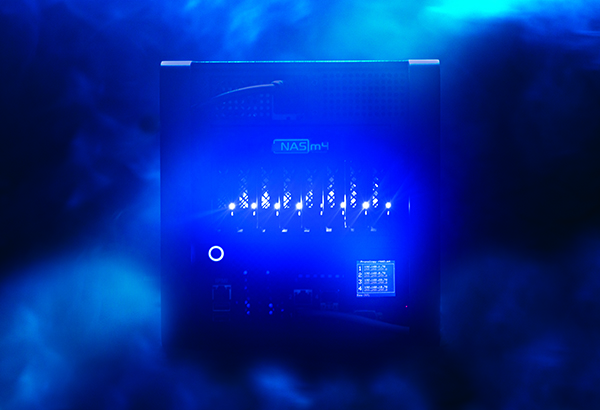

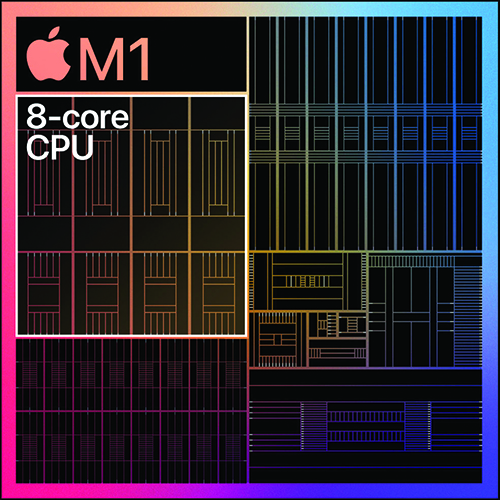

Despite these exorbitant costs, fabrication plants are relatively short-term investments. The fabrication designs used in each plant are often obsolete within just a few years. As our need for faster and smarter devices grows, so do the demands we place on any given circuit board. A practical example is the 3.5-inch spinning disk hard drive. Fifteen years ago, these drives were commonly sold in units measuring in the gigabytes. Today, you can buy an 18-terabyte drive that conforms to the exact same size and specification. Increasing the data storage by that amount without changing the size required that more transistors—components used to conduct electrical currents—be packed into the same space. In fact, it has commonly held true that the number of transistors in a densely integrated circuit roughly doubles every two years. And this principle applies across the entire spectrum of electrical manufacturing. Smartphones, tablets, personal computers, televisions, gaming devices, cars, and anything else you can think of with a screen or plug. Therefore, each multi-billion-dollar facility only has a short window of time before they are manufacturing hardware that is no longer in wide demand. By the time one facility begins production, its replacement is already being built. It is a constant race to put up the next plant in time to keep up with innovation.

Then the pandemic hit and everything stopped. Demand for electronic devices skyrocketed. COVID-19 forced us to become more reliant on our phones and computers than ever before. Schools raced to send hundreds of thousands of laptops and tablets home with students in order to enable remote learning. Companies were forced to set up infrastructure in their employees’ homes. Assets had to be distributed via the cloud like never before. All of this required record amounts of hardware. And all the while, production on new fabrication plants had shut down. Intel, Samsung, and TSMC—the three largest suppliers of semiconductors globally—all have new plants in various stages of construction, with plans for additional plants being rushed into action to catch up with demand.

This chip shortage has resulted in limited availability of consumer electronics across the markets worldwide, leading to sharp price increases on goods. However, this might just be the beginning. As the current estimates foresee the shortage lasting until 2023, this shortage will have long-term consequences across every tech-reliant industry.

In the meantime, we find ourselves in a deficit. The gaming industry finds itself caught between two hardware generations as Sony and Microsoft’s new consoles remain difficult to procure at market value nearly a year after their launch. High-end graphics cards, essential to gaming, video processing, and crypto-mining alike, are impossible to find in stores, with scalpers charging more than double suggested retail value on sites like eBay. The dwindling supply of high-capacity media drives has already forced data storage costs to rise. However, auto manufacturers have been hit the hardest so far. The growing ubiquity of Wi-Fi access, global positioning systems, Bluetooth integration, and advanced safety features in cars combined with the rising demand for all-electric vehicles lead auto manufacturers to integrate computer components like never before. Now production has slowed to a trickle as companies struggle to source the necessary components.

Though initial projections hoped for an end to the shortage by early 2022, complications arose. Drought conditions in Taiwan have slowed production in TSMC plants, which can consume up to sixty-three thousand gallons of water per day. Trade disputes between the U.S. and China in 2020 have impacted supply lines today. Now the situation is expected to last until at least 2023.

Political leaders around the world have pledged to end this chip shortage as swiftly as possible. In the United States, President Joe Biden signed a February 23 Executive Order, directing U.S. agencies to work with industry leaders to strengthen supply of semiconductor and, after a 100-day review period, recommended Congress allocate fifty billion dollars for the construction of new plants within the nation in order to reduce U.S. dependence on overseas manufacturing. Unfortunately, industry experts expressed concern with such a figure, with Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger referring to it as “a great first step.”

If further steps are not taken, the problems we’re facing today may only be the tip of the iceberg. Our industry, one of the most tech-driven industries in the world, will be particularly susceptible to the rigors of this problem. So what should we expect to see?

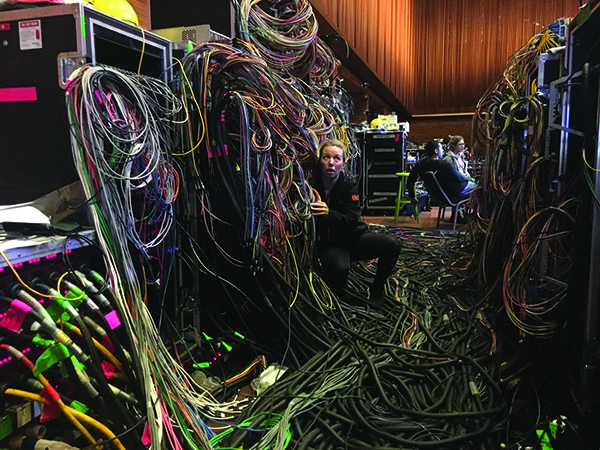

The cost of gear is going to go up. Film and television sets use highly specialized tools and all of those tools will be more difficult to source. New hardware releases may see delays as developers struggle to meet manufacturing quotas. Those that do see release will likely do so in limited supplies at a premium. Software releases may stagnate as companies struggle to acquire hardware for product development and testing. Moreover, storage media will likely become a problem. Our productions burn through terabytes upon terabytes of data every day. All of it needs to be acquired, copied, backed up, distributed, and stored using drives and as productions migrate to higher resolutions and larger codecs, the number of drives used on a given production increases. All of this will drive production costs up. As budgets balloon, pressure will grow across all areas of production.

The somber reality, however, is that it is difficult to predict exactly how this situation will unfold. The uncertainties of weather conditions, international disputes, and emerging viral strains cast a shadow of doubt over any projections made today. The only common consensus is that things are going to get worse before they get better. Violence has already broken out over product launches and restocks. Unrest is likely to grow as supplies run dry. Members are encouraged to take ample care when handling or transporting expensive equipment. Common sense practices should be observed. Never leave gear unattended or unsecured. Never leave equipment visible in a parked car. When coordinating third-party rentals through platforms such as ShareGrid, never invite renters to your home or equipment-storage location. If coordinating a large rental with strangers, bring a friend to the drop-off/pickup with you. Conduct rental drop-offs and returns in public, well-occupied locations. Take great care to preserve equipment for as long as possible. Replacements may not be as readily available as they once were. Above all else, be safe.

Though we hope we are beginning to see the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no doubt that its effects are going to continue to be felt for years to come. This global chip shortage highlights just how delicate our technological infrastructure can be and should serve as a warning of the dangers we face when it is disrupted. With climate projections predicting greater drought conditions in the future and a rise in natural disasters, we need to innovate like never before to ensure that we are ready for the problems of tomorrow. Our infrastructure will continue to face challenges but Local 695 and the whole of IATSE comprise some of the finest technical minds in the world. It is our job to lead the way in dynamic thinking and problem solving so that we can overcome the obstacles we are about to face and be an example to others in times of adversity.