by Steve Nelson, CAS

The common wisdom tells us that Puerto Rico is a great place to shoot a pilot but not the series. It’s too far, the weather is dicey with a hurricane season, not enough infrastructure, language issues, too exotic, in our case, the landscape required too much expensive CGI to give it the right Amazonian look, all the usual complaints that make me wonder why so much production has left Los Angeles. So when we got our midseason pickup order, no one was surprised that we would take the show to Oahu, despite the very generous 40% incentive offered by Puerto Rico to stay.

There are some favorable reasons to go west: only five hours direct flight from Los Angeles, relative lack of hurricanes, more English, miles not kilometers, better sushi and cycling, more infrastructure including a recently built actual soundstage and enclosed water tank (which the network wants to tie up), a better jungly look and more varied, easily accessible, locations. In Puerto Rico, however, we had an actual navigable river—once we hauled the boat, at high tide during the full moon, over the sand bar at the river’s mouth—while it is well known that there are no rivers in Hawai’i, at least on Oahu. Hawai’i’s incentive is only 15%–20%. The unvoiced thought was that our show is a supernatural thriller kind of like that other show whose name we tried to avoid mentioning that shot for six seasons on Oahu, and since no one could think of a similarly successful show coming out of Puerto Rico … aloha! (I prefer Puerto Rican rum, but I guess that’s not enough reason to stay.)

IF WE’D KNOWN THEN WHAT WE KNOW NOW or THE SAME ONLY DIFFERENT

As a seven-episode midseason replacement, we’ll start a bit later than the rest of the network season, late in August and go for about three months on Oahu.

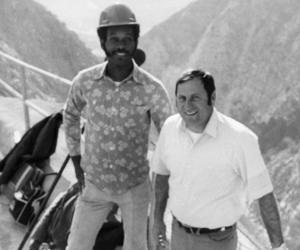

There weren’t many returning to continue the voyage up river: Our DP, John Leonetti, and his key grip, key makeup, accountant, producers and line producer, execs, our Puerto Rican 2nd 2nd AD (long story), our director, Jaume Collet-Serra (for the first episode), and me. Knox White was not available to make the Hawai’ian scene so I enlisted my old friend, Tom Hartig, to join me. I’ve traveled and worked in many faraway places with Tom and there are few better companions, and no better boom operator and set runner, so I was excited to have him back. On the recommendation of Richard Lightstone, I contacted local sound utility Jon Mumper, who, since he wasn’t working on the other show going at that time, Hawaii Five-O, was happy to join us. Jon was the only member of the sound department to survive all six seasons of Lost and, like so many of the crew there, his career and skill set was forged in that crucible. He came through it fine and was a solid asset to my crew. He is amazingly stoic about things; I guess after six years of that show—so many stories!— everything else seems easy. We also had local John Reynolds on hand for our second units.

This was not my first visit to Hawai’i but my first time working there. I had resisted the calls to work on Lost, now would be my time. P.R. was a fun place to work; though always exotic it was not always easy. There has been so much filmmaking for so many years in our 50th state that it felt very normal to be there. Normal, but not to be taken for granted; there were so many locations where the natural beauty was absolutely stunning. Even when you’re stuck in the usual horrible traffic jam, there’s something nice to look at, at least a rainbow or something.

We would not be staying in a hotel this time; that was not an option. Rather, we would be given a housing allowance, a rented car and per diems and invited to find our own place to live. Negotiating with landlords can be a little tricky considering all the uncertainty of production work. Tom and I decided that we would pool our resources to get a house together. With the help of our production staff we found one in Kailua, the nice beachside town where President Obama stays, on the windward side about midway between the stage near Diamond Head in Honolulu and the Kahana Valley where our “river” was located. The out-of-town crew was mostly split between Honolulu/ Waikiki and our side of the island. A word of advice to anyone who is driving there: watch and obey the speed limits on Oahu. They change suddenly and arbitrarily and there are many cops in unmarked cars lurking about. And on the advice of our teamsters, peel off the rental company bar-code ID sticker and put on a local bumper sticker so as not to look totally like a tourist and invite break-ins.

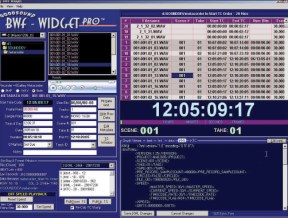

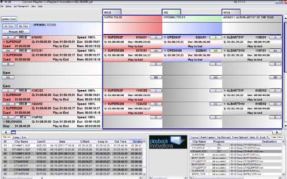

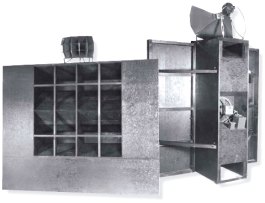

Our friends in Post-Production and our bosses were quite happy with the work we’d done on the pilot, so I decided to keep the same basic approach and try to fine-tune it and to anticipate some of the challenges a new season and location might bring. On the pilot, Production had been willing to cover a week or so of rental for my over-the-shoulder rig but for the longer run, the network was unwilling to subsidize additional equipment I thought necessary to achieve the results they liked in the pilot. The network, in this case ABC, picks a number that someone believes is appropriate for sound equipment rental with little regard for actual job requirements. Then you must provide competitive bids to justify the number they gave you. As “employee vendors” we are in a special category; it seems that the networks would rather pay more to an outside, approved, vendor than to us. There are exceptions, but it is becoming more challenging to provide adequate technical support at these rates. Nevertheless, we all love a good excuse to buy new equipment, especially if we know it will be necessary for a job and good to have for the future. So when it came time to gear up for the Hawai’i shoot, I found a great deal on a slightly used Zaxcom Fusion 10, which is basically a Deva 5.8 without the DVD burner. The Nomad was not yet available, and while it makes some tremendous advances in a very small package, I definitely needed all eight knobs that the Fusion sports, so it was a good choice for the job.

When using Zaxcom recorders in a bag, you want to avoid using their very noisy onboard slate mike. Robert Kennedy, former Coffey Sound specialist, helped with a clever solution that works really well with the Fusion and Deva and requires no modifications. Using the Disk Mix and Output matrices, it is easy to route an external headset mike to slate, public Comteks and also to IFB for a private line to my crew. This requires only a custom cable using the “Camera” connector on the Deva. Although I had to give up one mike input, this is much more versatile than on the pilot when I had only the Comtek for everybody, and it avoids using the bulky 25-pin output connector and snake.

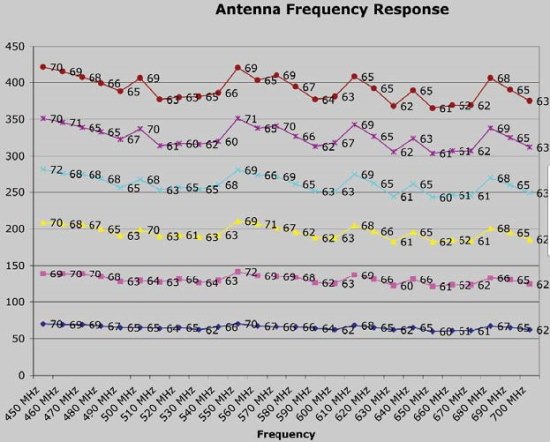

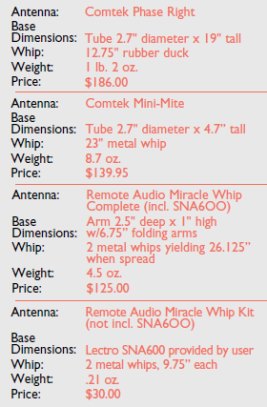

I also acquired a Venue Field and loaded it with the appropriate VRT modules and a larger Petrol bag that fit better than the smaller one I’d had in Puerto Rico. For Hawai’i, I got a couple of dipole antennas instead of the sharkfins, thinking that would still increase my gain and not take up so much space. Also, I discovered that Petrol uses these little clips to attach all those pouches to the bag; I got the matching clips from Petrol, screwed them to the dipole mounting hardware and I could easily mount (and unmount) the antennas right to the bag. Ultimate range was not quite as good as the log periodics, but the lack of directionality is helpful, especially when talent is moving in three dimensions all around and I’m not sure exactly where they might be.

Since the Fusion lacks a DVD burner, I thought this would be a good opportunity to begin to wean myself off DVD-RAMs and move toward other media. At this point, the network still wanted archivable media. (I don’t blame them; it is to my way of thinking a significant leap of faith to hand over your day’s work on a tiny piece of media that will come back blank, having been downloaded to a drive. As our work evolves, this will be an ongoing discussion, but for now it seems to be someone else’s problem.) The compromise was that when I worked off the cart I would deliver, as usual, two DVDs, one multi-track and one single-mix track, and when I was in mobile mode, I would deliver a multi-track Compact flashcard. Since the picture and sound transfer was happening back at the production office, the media turnaround was pretty quick. Certainly digesting all the picture data was the main concern. (On the pilot, I just finished as of this writing, I used no DVDs at all. I delivered to DIT the two flashcards and within minutes he’d downloaded them onto the drive with picture and off they went for syncing.) Although I’ve always admired the robust nature and flexibility of our DVDRAM disks, these C/F cards are fast, flexible, and in the long run, very cost efficient.

NEVER THE SAME RIVER TWICE

In Puerto Rico, the boat playing the part of the hero boat, the Magus (think poor man’s Calypso), was a real watercraft, artfully aged. But that was another ocean. We also had something more like an actual river there and we could steam for quite a while before turning around. On Oahu, our main river location was in the beautiful Kahana Valley, up the windward coast, which features not a river, but the Kahana Stream. It comes down from the wet mountains and runs shortly to the sea, suitable mostly for kayakers and stand-up paddlers. Though not very deep, this stream is prone to flooding during the rainy season and there is a low bridge under the road at its mouth. The valley is incredibly lush with suitably tropical foliage and gorgeous mountains rising dramatically. The solution of how to get the Magus in here was to build our own and assemble it on site. Hawai’i is the birthplace of surfboards, so that technology was adopted. The construction crew shaped blocks of Styrofoam and covered them with fiberglass—just like a surfboard. They built a steel superstructure on top and constructed our floating set, which bore a striking resemblance to the original. The whole thing, about 60 feet long, with a main and upper deck, only drew about 18 inches of water, but it lacked power, a rudder and keel. It also had no head and no smoking section (much to the distress of Jaume Collet-Serra, our director). Nevertheless, fully loaded with cast, crew and equipment, we could push or pull this rig in a similar fashion as in Puerto Rico, about a quarter mile up and down our beautiful river before we ran out of room. (You can easily see it on Google Earth.)

There were some advantages to working on our floating set (not really a boat). It was more spacious and easier to work on than the original; it had less sharp metal pieces to bark your shins on and wider passage along the gunwales. The first time it rained we discovered it was not really watertight but that was quickly remedied. With less metal, it was more transparent to RF. It was the lack of steering that gave me the most grief. Lacking rudder and keel to help keep it on course, plus a less than symmetrical hull, it tended to move like a pig on ice when pushed, that is, anywhere but where you wanted, and often aground. The remedy? A pair of Zodiacs on either side of the bow keeping us on course. This was not a happy solution for sound; those little outboards are noisy and the operators were not too clued in to the dialog being more concerned with keeping things moving forward and out of the weeds. In addition, the main powerboat pushing us was not the same gentle giant that we had back east, and the generator it carried was also louder, giving us more noise to bury in the final mix. So began the ongoing negotiations with Marine and Electric: changing the positions of the Zodiacs, building housings for the generator (worked great until it overheated), swapping generators. Constant vigilance was required to keep things to a manageable roar, as were fingers on faders to keep it out of open mikes. Next season, if there is one, I will demand a steerable floating set!

I brought along one of those cute Backstage Mini-Magliners, thinking that it might be nice to have a platform when on the Magus or when four-wheeling through the bush. We did bring it on board and it was helpful, but as we were constantly moving around the boat, it seemed that there were always too many people aboard and not enough space so it was in the way. In prep there had been talk about a Sound Gator for getting to difficult locations. In that case, we would have tied the Mini down and used the Gator as a mobile unit, but as it turned out they were, for the most part, very gentle with our locations. We shot a lot in what we called “parking lot jungles”: park the truck, roll the gear a little ways, and there you are. If you worked on Lost, you would be familiar with many of these places. We did use the Mini for some of these locations, particularly because it was easy to just grab the bag, leave the cart and go. Next time, I’d like to try the Zaxcom Mix-8 with the Fusion. That way, if I am able to find a comfortable place to sit and work, I’ll get the ease of working with faders instead of knobs and if I have to run, just unplug it and go. Plus, I think it’ll be great for insert car work.

Sooner or later in our line of work, you are going to encounter a situation where, one way or another, your actors are going to get wet. If your show takes place in a boat—on a river—in the tropics—the odds go way up. This is rarely not a problem for us. There are many ways to get actors wet but probably only two main categories: submersion (or, I suppose, immersion) and water from above, i.e., rain. Both are special sources of pain for us. Let’s take the case of rain, the sort generally provided by our special effects brothers. How does the rain get up into those towers? By using a very noisy pump. So if you are able to keep your boom mike dry and free of raindrop impact noise (Remote Audio’s Rainman is a very nice upgrade from the old hog’s hair special), then chances are you’ll be fighting SFX noise and the ambient sound of “rain,” but you might be lucky enough to get a nice clean close-up. If you’ve been paying attention (see last issue, Part 1), you’re aware that this is probably not an option for us on The River. We’re pretty much left with Plan A: Wire ’em all.

The climactic scene of one episode involved a rainstorm of biblical proportion, at night, on the boat. The saving grace was that the boat would be docked. As the weather gods would have it, rain was forecast for that Friday night. Another opportunity to show off the beauty of the Aviom system as I stayed in the dry comfort of our truck (with my wife and daughter who were visiting), while we rain-bagged the RF Cart and put it at the water’s edge near the Magus.

The scene involved much physical action and much water and cameras in all the usual places—handheld and mounted. Thanks to Tom we were well stocked with industrial-strength condoms, which keep the transmitters dry under most circumstances, but given the expected deluge, we decided to take it to the next level of water resistance and rented some Lectrosonics MMs. (The new Lectro WM looks like a great new alternative for a water resistant transmitter.) Choice of lavalieres in this wet situation is important, though in my opinion not as important as one might think. The Sanken COS-11 is perhaps more water resistant than advertised. I had learned this on the pilot, where an actor (no names on location!) accidentally put one in the water during an unexpected dunking in an improvised scene. It made quite a sound when it hit and was apparently inert, but after carefully drying it and leaving it be awhile, it actually came back to us. (Sanken now has the COS-11D for moisture and reducing digital interference.) Nevertheless, the COS-11 is not my first choice for getting wet; that honor would go to the Countryman lavs. Their Classic Omni (like a smaller Tram) is good for water work, as is the B-6, which most of us carry, though probably without the right screw-in connector for the MM. Another choice, the Lectrosonics M-150 or 152, the lav that Lectro used to include with the purchase of a transmitter, is surprisingly good in the wet and if it goes down, it won’t feel like such a loss.

After this dissertation on which lavalieres to use in the rain, I will share this: If you must have the mike hidden under their clothes, it doesn’t much matter which lavaliere you deploy in a scene where the actors get really wet. Once the wardrobe becomes saturated, although the waterproof mike will be safe, it will not deliver natural sounding audio. As the clothing approaches saturation the material becomes less acoustically transparent and, though it might not sound “underwater,” the frequency response is far from flat. You might get lucky with take one, or if the actors start each take with dry clothes, you’ll get another chance. Some might not get as wet as others, so perhaps you can pick up dialog on another actor’s mike, or maybe it’s possible to sneak in a plant mike. With a tiny lav like the B-6 it might be possible to hide it in plain sight, out from under the wardrobe, especially at night, but then, of course, it is susceptible to wind noise and the possibility of taking a direct hit from a raindrop. In this case, the action was meant to be wild and chaotic in the dark with a King Lear storm blowing, which actually gave us some latitude. With a combination of “all of the above” and some good luck we managed to get what we needed. So much of what we do requires multiple options, quick reactions and improvisational skills. On top of all that, layering in more wind and rain fx in the mix can help cover a multitude of sins.

During our relatively short season—seven episodes, eight days per—we had some fun telling scary stories. We got to hit some classic horror tropes: jealous ghosts, animated dolls, mysterious and unfriendly natives, zombies, demonic possession and the series finale, an exorcism. There was also the plot development of some secret quasi-governmental organization that was behind all the mystery as Dr. Cole searched for the source of the magic in this beautiful but threatening place where the laws of nature have no sway. We used all kinds of special effects: rain, wind, fog (not easy on a river on the windward side of the island), water tank and more, and quite the arsenal of visual effects. As always, the mission of the sound department, producing appropriate and useable tracks, is complicated by all this trickery. In the case of The River, we really had to step it up because of the multitude of cameras. We got to do a little recording session, luckily on stage, for playback on the moving boat. It featured guitar, accordion and a vocal duet. We also provided playback of scary creature sfx and eerie music for actor motivation, nothing too complicated but rendered more challenging considering the location and the cameras. As was the case on the pilot, our work was made easier with the help of a very talented and supportive crew and production staff and a wonderful cast who themselves had to go through some pretty rigorous paces. Also, we were working in some of the most beautiful places ever!

The virtues of Hawai’i are well known to anyone who has traveled there; most of us go for vacation, but there are many far worse places to be shipped off to work. One hears so many stories about the challenges of a location and the specter of Lost looms large there (“Do you remember the season it rained for 40 days straight?”) but we were fortunate with the weather, late summer to Thanksgiving, and it wasn’t quite the mudfest I had feared. To be sure, we had rain, but as in Puerto Rico, the locals know how to deal with it and you’ll be covered almost before the first raindrop lands. Heat and humidity are always a problem in the tropics and shooting on the windward side meant that we had some wind as well. Okay, and when I was on my bicycle, sometimes it felt like I was riding though a carwash, hot, then rain, then wind, and always sweat. Of course, I was commuting on a bicycle along the beach, over some mountains, through some towns on one of the world’s great destinations. Really, who can complain? You’re in Hawai’i, and I’m happy to say that it hasn’t been ruined for me as a vacation destination.

The circumstances of working on a distant island are similar to other faraway locations only sometimes more so. There are limitations: you can’t just send a driver to the rental house to get what you need, so you make do with what you can find there—or plan ahead. For us, there is only one suitable sound truck on the island and it was already in use by Hawaii Five-O. We got by with a (slightly) modified cube truck. Well, actually two, as the lift gate on the first was deemed unsafe. Then the supposedly safer gate on its successor broke while in use. Somehow no one was injured and the gear escaped unscathed and the gate was repaired. Which brings me to a major difference between shooting in Hawai’i and Los Angeles. Just before leaving I had completed the latest required Safety Passport classes. I arrived ready to implement all the good new rules and guidelines I’d learned only to find that not only were they not required there, but even normal safety guidelines are ignored, if not scoffed, by the locals. Is it really such an imposition, for example, to keep the fire lane on stage clear of obstructions? I am told that this is a concern at many of the newly popular production centers out of Los Angeles. I would like to see all union crews and signatory productions held to the same safety standards. As I write it has been determined that despite all our best efforts we will not be returning for another voyage up The River. I guess we’ll never find “the source.” We had our fans but alas, not enough to make the network cut. My wife is particularly disappointed as she was looking forward to spending her teaching sabbatical in our house in Kailua.

Doing this show was quite an adventure, both in terms of location and the challenging nature of the work. Admittedly, it was a bit surprising at this point in my career to strap on all this gear and go running around like an ENG or reality show guy. It wasn’t that we in Sound were doing anything especially innovative, just more of it than would be considered normal in the context of a one-hour network episodic show. (Not quite like American History X where Tom and I had to “invent” wireless boom to compensate for the antics of director/camera operator Tony Kaye. Seems pretty basic these days, but with the non-diversity VHF RF of yesteryear it was pretty challenging!) Of course, when you consider the up-to-14 cameras we used on The River, the whole notion of “normal” is left far behind. (We might have shot a million feet of film onAHX, but it was all one camera.) Once you get your head around it and commit to this crazy way of working, you just keep moving forward. It wasn’t full-on every day; the reality TV mode was often interrupted by the old normal, which meant working off the cart, albeit with more lenses than seems right. And now that I have this studio-in-a-bag set up, it is amazing how appropriate it is for other gigs.

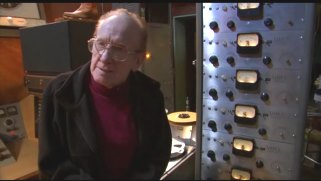

I’m happy to say that the unorthodox working style resulted in tracks that were a component of what I think is the best sounding television show I’ve ever done. The supernatural themes provided a broad canvas for our very creative cousins in post, Paula Fairfield, supervising sound editor, and Dan Hiland and Gary Rogers on the board at Warner Bros., plus a very suspenseful score by the great Graeme Revell made for a very effective sonic environment. Our dialog editor, Jill Purdy, was very happy with the tracks we provided and used only the bare minimum of ADR.

Thanks to all for the challenging and fun adventure and the excellent opportunity for growth in my craft! Adíos and aloha!