by Scott D. Smith, CAS

Author’s note:

This piece is a continuation of the article from the fall 2010 issue of the 695 Quarterly, which examined the early beginnings of the Local. While there is a wide range of historical events pertaining to the Local, I have chosen to focus on the events of 1933. Not only was this year crucial to the survival of the Local (and the IATSE as a whole), but it also closely mimics our current economic situation. All of the caveats contained in forward of the previous article apply here.

1933

While it is safe to say that 1932 was not a year that would be recalled fondly by most rank-and-file workers in Hollywood, few would have predicted the events that were about to be unleashed in the first quarter of 1933.

Although the general unemployment rate for the nation had risen to nearly 25%, many who toiled on the Hollywood lots were still fortunate to be working, in some cases making more than their counterparts elsewhere in the country. However, taken as a whole, the annual income for the average worker in the film industry was nothing to be excited about. While daily or hourly salaries may have looked attractive, earnings were frequently offset by long periods of unemployment with no income at all. (This was well before the advent of Social Security and Unemployment Compensation.)

Some studios, like United Artists, made efforts early on to keep their sound crews employed when off production. This might mean that someone who worked as a First Soundman during production would end up spending time as an Assistant Re-recording Mixer on the dub stage. Second or Third Soundmen, if they had technical skills, might be put to work in the maintenance shop between pictures.

This arrangement generally worked well for both the studio and employee. It provided steady employment for sound crews, which were still in rather short supply in the early 1930s, and allowed the studio to maintain a core staff of technicians to service their productions. This meant less training of new hires, which could be a headache for the sound department heads, as they sought to integrate fresh talent into their recording operations.

Not all studios subscribed to this practice, which meant that as soon as a show was finished, the sound crew would be idled at no pay until they were hired for the next project. While the studio system of the 1930s and ’40s may have the appearance of offering a more stable income for some crafts, the reality for many workers was similar to that of today, where employment was for the length of a show only.

Photo from Vitaphone set for a George Jessel short on Manhattan Opera House set ca.1926. The CTA microphone rigging is typical of the work that would be performed by the “sound grips.” (George Groves Collection)

It was sometimes not even that if you were unfortunate enough to be fired during production, a not uncommon event!

Given all these factors, it is understandable that most crew members during this period would strive to remain on good terms with both the directors and department heads, despite production schedules that called for six- or seven-day workweeks, 12 to 14 hours a day, and no overtime. While no one, from directors and actors on down, was happy with these conditions, the alternative was equally unattractive. The studio bosses knew this and the terms were made abundantly clear to all.

Those who didn’t play along would quickly find themselves unceremoniously escorted to the studio gate and thrown into the street along with their belongings. Not even department heads were exempt from such humiliation. Should you be deemed a “troublemaker,” your name would end up on the studio “blacklist” (which was rumored to have been exchanged freely among studios). Depending on circumstances, if you were fired at one studio, you might never find employment in Hollywood again.

The New Deal

On March 4th of 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, having just narrowly escaped an attempt on his life the previous month in Miami (the bullet intended for him instead took the life of Chicago Mayor Anton J. Cermak), was sworn into office. It was during this inaugural address that he famously proclaimed: “the only thing we have to fear is, fear itself.” As it turns out, there was plenty to fear…

With Democrats firmly in control of both the House and Senate, FDR wasted no time enacting a series of legislative changes that were deemed necessary to restore confidence in the U.S. financial system. The first of these was a “Bank Holiday,” instituted within hours of its passage on March 9.

This act, known as the “Emergency Banking Act,” sought to restore confidence in the solvency of U.S. banks. Similar in many ways to the action taken by our current administration, this act called for tough new reserve requirements on banks, as well as providing federal bailout money for those banks deemed crucial to the functioning of the U.S. financial system. It also removed the U.S. from the gold standard.

On Monday, March 9, all banks in the United States were ordered closed while federal examiners pored over their balance sheets to determine their solvency. After four days of non-stop grilling by the Feds, just one-third of U.S. banks were deemed sufficiently solvent to be reopened. Although just a fraction of the banks were left standing at the end of the week, the effort was largely judged a success. The effect on Hollywood, however, was disastrous.

More Pain Ahead…

On Monday, March 6, two days after Roosevelt’s inauguration (and the same day as the Bank Holiday), Will Hayes (architect of the much despised “Hayes Code”) called an emergency meeting of the MPPDA Board of Directors. This private meeting, which lasted long into the night, was attended by studio heads from most of the majors, including Sam Goldwyn (Samuel Goldwyn Studio), Nick Schenck (M-G-M), S.R. Kent (Fox), Carl Laemmle and R.H. Cochrane (Universal), Jack Cohn (Columbia), Albert and Harry Warner (Warner Bros.), Adolph Zukor (Paramount) and M.H. Aylesworth (RKO). Oddly enough, Hayes was more focused on furthering his agenda regarding the “immoral” content of current films, rather than addressing the dire economic straits facing the industry.

Despite this, initial plans for industry-wide salary cuts were hammered out among the attendees, and later presented to other studios. These called for studio employees to take a substantial reduction in salary for a period of eight weeks. Workers who made $50 or more a week were to have their salaries cut by 50%, while those making less than $50 per week would receive a smaller reduction of 25%. A minimum salary floor of $37.50 was proposed for those making more than $100/week and a $15 floor for those making less than $100/week.

However, not everyone subscribed to the “party line.” Having implemented its fourth wage reduction just three weeks previously, Universal was initially against the cut. United Artists (led by Mary Pickford and her partners), was flat out against it. And there was further turmoil as some studios later proposed a permanent reduction in wages.

The reaction from labor, including writers, musicians and actors, was swift and decisive. On March 9, at least four IATSE locals (including 695) announced that, if the studios went ahead with their plan, they would strike. Adding to this already-tense atmosphere, an earthquake registering 6.3 on the Richter scale occurred in Long Beach late Friday afternoon of the same week. The quake caused 120 deaths and $60M in damage to areas in Long Beach and Los Angeles. People’s nerves were really frayed.

While the actions of the Roosevelt Administration to restore confidence in the banking system were mostly laudable, the speed at which the legislation had been enacted left little time to analyze its effect on various sectors of the economy. Studios, already in dire straits due to falling theater attendance, relied heavily on the flow of cash from daily box-office revenue to sustain their operations. With cash flow completely shut off due to the bank holiday, even relatively solvent studios began to founder.

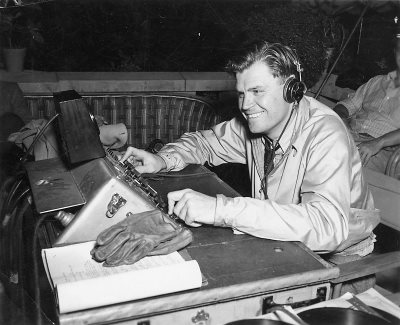

United Artists sound crew ca. 1928. Ed Bernds in middle row, second from left. From “Mr. Bernds Goes to Hollywood” (Photo courtesy of Scarecrow Press)

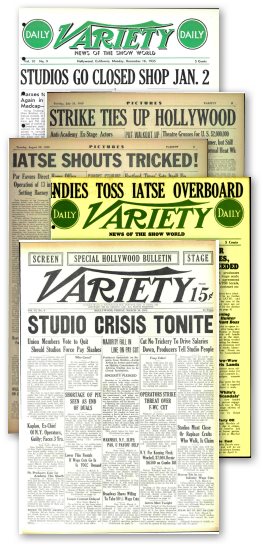

The March 14, 1933, issue of Variety succinctly summed up the total effect of labor cuts on the industry: the reductions of March 1933, combined with those of the two previous years, totaled more than $106M. All told, film payrolls at the majors were reduced from $156M in 1931, to just $50M in 1933, a staggering cut in the workforce. It was estimated that at least 90,000 employees were eliminated from studio payrolls during this period. Keep in mind, this was just for the major studios. Cuts at the independents varied, with some reporting similar salary reductions. Some, however, held out as long as possible before following suit.

(In a bit of irony that could only happen in Hollywood, a number of production companies attempted to cash in on the story of economic crisis, with more than one studio announcing plans to mount a production while it was still timely. However, on March 12, Monogram Pictures announced that their production start for Bank Holidaywould be delayed for a month. The reason cited: the bank holiday!)

Many issues arose as a result of the initial meeting on March 6th. Which employees would the cuts apply to? Would film exchange, distribution and theater employees be included in the wage cuts, or just studio workers? Clearly, some aspects of the plan had not been well thought through.

Confusion abounded as studios, actors, directors and crews attempted to sort out the terms of the salary cut. Irene Dunne, working on the RKO picture Silver Chord, refused to sign the 50% reduction without consulting her attorney, effectively shutting down production. Other actors made similar demands.

Despite these events, the film exhibition business continued to thrive for certain pictures. David O. Selznick’s production of King Kong opened in New York on March 3rd to great fanfare. Shows ran simultaneously at both the 6200 seat Radio City Music Hall and the 3700 seat Roxy Theater across the street. Crowds lined up around the block and all 10 shows were sold out for four days running, setting a box-office record. Eventually grossing $2M in its initial run, King Kong was the first film in RKO’s five-year history to turn a profit. Clearly, there were few bright spots still left in the picture business.

Labor Guilds

As the battle over wages and working conditions raged on, groups representing various studio workers became even more fractured. Actors, who had made a previous push for unionization in 1929, were anxious to establish their own bargaining group. From the previous foray made at that time under the banner of Actors Equity, six disgruntled actors met to form the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). By November of that year, they had 1,000 members, including the likes of Gary Cooper, James Cagney and George Raft.

Similarly, the writers, who felt that the Academy was nothing but a “company union,” broke away to form the Writers Guild. With rudimentary offices shared with SAG in a four-story Art Deco building on Hollywood Boulevard, both guilds made a push for recognition by the studios. Although SAG had already been recognized by the A.F. of L., the studios, still furious over their withdrawal from the Academy, refused to bargain with either entity. Another four years would pass before they would finally gain acceptance.

The Strike of July 22

Although Local 695 had been successful in signing agreements with many of the independents, as well as making some inroads into Warner Bros., most of the majors refused to budge. An ultimatum had been issued previously to Columbia Studios that if they did not ink an agreement with Local 695 by 10 a.m. on July 8, the soundmen would walk. In an effort to accommodate the studio, this deadline was then moved to the next day (July 9). The deadline was then further extended to 2 p.m., and then 3 p.m. Later, Columbia general manager Sam Briskin called to request a further extension. He maintained that the studio was signatory to the Basic Agreement, so there should be no strike. For their part, the Executive Board of 695 considered this simply a stalling tactic, as 695 was not included with the four IATSE locals represented under of the Studio Basic Agreement. In fact there were nineteen other unions or guilds working on the lots, none of whom were covered under the agreement.

In further discussion over the next ten days, Columbia (through Pat Casey, acting on Columbia’s behalf as the rep for the producers), took the position that this was a jurisdictional dispute between IBEW (International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers) and Local 695 and refused to budge. On Thursday evening, July 20, Local 695 Business Agent Harold Smith presented a formal contract proposal to the majors (as well as to independent producer Bryan Foy of Eagle Lion Studios), giving them until midnight Saturday, July 22, for an answer. The gauntlet had been thrown down. As midnight Saturday approached, with no answer from Pat Casey or the studios, a strike was called.

On Monday the 24th, Variety reported that many of the IATSE crafts would honor the action, including the Camera Local (659), Film Technicians (683), Studio Projectionists (150), Studio Mechanics (37), as well as all film lab technicians and cutters. However, the Carpenters, Studio Electricians (working under IBEW) and Musicians unions claimed they were not part of the action, and did not plan to honor it.

The major producers remained firm in their position, still claiming that it was a jurisdictional issue between Local 695 and IBEW, and planned to appeal to Washington to settle the dispute.

The studios, in a grand effort to prove that they did not need Local 695, continued production on the following Monday using replacement workers. Paramount started early that morning, working without sound, rehearsing cast members while they trained new technicians. United Artists brought in replacements from ERPI, Metro brought over men from their recording operations, replacing them with telephone and radio technicians (although they admitted they “had no idea the kind of sound it will get”). Men working under the auspices of IBEW were also transferred from other departments, some of whom already had related training in recording and broadcast operations.

The studios also placed ads in the Sunday and Monday papers urging men with broadcast and telephone experience to apply for positions. Radio appeals were broadcast and, by the end of the day Monday, more than 300 positions had been filled.

For their part, the members of Local 695 were exemplary in their behavior during the strike. Despite increased police presence at some of the lots, there were no reports of any trouble. When soundmen picketing the gate at RKO were asked to disperse by the studio police, they did so quickly. In addition, there were no reports of problems from productions working to the midnight deadline on Saturday.

The studios appeared ready to deal with the action as long as needed. They offered bunks on the lot for replacement workers, so they wouldn’t need to cross picket lines. They also culled additional staff from research operations.

Difficult Decisions

Despite the havoc unleashed by the threat of salary cuts, production did manage to continue at most studios, albeit at a much slower pace and with varying degrees of success regarding the quality of their output. While most crafts supported IATSE’s stand against the cuts, the reality of trying to survive during extremely difficult times meant that many workers were ready to cross the line to gain entry to jobs that, even in good times, might be unavailable to them. It also gave studio heads the opportunity to try to break the hold of IATSE over many of the crafts.

Two years would pass before the National Labor Relations Act would be enacted. There was nothing to stop various organizations from mounting a campaign to represent workers. It was “open season” for labor, with a variety of splinter groups claiming representation for the various crafts. Local 695, previously part of Studio Mechanics Local 37, had IBEW to contend with. As the union claiming jurisdiction over sound technicians involved in installation and, at some studios, sound maintenance, IBEW was in a prime position to launch an effort to raid the soundmen of 695.

With the breakdown in negotiations between the studios and Local 695, IBEW launched a bold effort to force the studios (and Local 695) to bow to their demands. Because IBEW controlled all electrical operations such as powerhouses, generators and power distribution (although not set electric, which was under IA jurisdiction), they were in a unique position to gain control. According to an article in the July 25, 1933, issue of Variety, Harry Briggerts, the national vice president of IBEW (and the man in charge of all IBEW locals), stated that if the producers negotiated with the soundmen (Local 695), he would “pull all his men from the studios.” He also claimed that the American Federation of Labor had granted IBEW jurisdiction over sound operations, further weakening Local 695’s position.

Studios could perhaps function without qualified sound crews but they certainly could not do without electricity. Therefore, the IBEW had both Local 695 and the producers exactly where they wanted them.

Doomsday for the IATSE

As a result, Local 695 was effectively shut out of their bargaining position with the studios. This impacted not just the soundmen, but all of the IA locals that the producers were intent on breaking. Chaos reigned. By August 14th of 1933, the number of workers who had split from the IATSE ran into the thousands. The membership of Local 37 alone, numbering about 3,000 before the strike, saw its ranks decimated to just a few hundred members.

A similar scenario was taking place within Camera Local 659. As studios backed away from direct negotiations with the IATSE, many of the cinematographers (but not operators or assistants) pushed for recognition under the auspices of the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC). As nearly every member of the ASC was also a member of the IATSE, it is unclear what the advantage may have been to the members by switching bargaining to the ASC guild, other than having their wages reduced. It also caused a significant rift within the membership, which further weakened their position with the studios.

At this point, studio owners boldly proclaimed the strike had been bust, and that production had returned to normal. (Later on, however, some reps privately admitted the strike had cost the studios about $2M in lost production time, not to mention problems caused by poorly executed work.)

The National Recovery Act

Simultaneous to the events taking place in Hollywood, the Roosevelt Administration in Washington was busy passing New Deal legislation intended to speed up the economic recovery. On June 16th of 1933, Roosevelt signed a bill creating the National Recovery Administration (NRA), charged with putting in place a set of controls for labor and industrial production. This act, which grew to affect between 4000 and 5000 businesses and 23 million workers, had a significant impact on the film industry.

In an attempt to rebuild their faltering reputation, the Academy, by now really just a representative of the studios, took an active interest in framing the rules contained in the NRA code. Over the next few months, numerous proposals were put forward by reps within the industry. Many of these related to caps on salaries as well as the ability of employers to “raid” the talent pool of other studios by offering more money. Another provision called for the creation of an “industry board” which would limit the salaries of the highest paid talent. This was not the way things got done in Hollywood and, when the code was finally released in late November, there were howls of protest. After a Thanksgiving meeting between Eddie Cantor (the head of the new SAG organization) and Franklin Roosevelt, the offending provisions were suspended. By 1935, the act itself was struck down as unconstitutional and many of its provisions were carried over into the new Wagner Act.

Local 695 and the IBEW

With their position significantly weakened by the threat of a work stoppage by IBEW Local 40, the soundmen found themselves in an extremely difficult position. Although they had managed to sign contracts with a number of the independents, the majors had (so far) successfully argued that this remained a jurisdictional dispute, and that they were simply obeying the mandate of the A.F. of L., which had given the IBEW jurisdiction over studio sound operations prior to the formation of Local 695.

With the studios allied to his cause, Larry Briggerts of the IBEW proclaimed that they had at least 2,500 men who had experience in sound (a highly debatable figure). While IBEW men had significant involvement in the installation and testing of sound equipment during the rush to equip studios for sound operations, it is doubtful that many men had experience in actual recording operations (especially since, up until 1927, there had been no recording operations!).

As a result of their influence over studio electrical operations, by early 1934, with the A.F. of L. backing them up, IBEW was able to secure contracts with many of the studios. However, the terms of the contract were less than favorable for those working under them. To entice the studios to sign, IBEW had offered a significant reduction in the wage structure as compared to that of Local 695. The studios, elated at the prospect of being able to rid themselves of Local 695, quickly signed on. This did not bode well for the men of Local 695, who, still without a contract that stipulated working conditions, would now see their wages further reduced. A dark cloud hung over the Local.

1934

By February of 1934, the IBEW had managed to make significant inroads into the studios, signing contracts for the staffing of sound operations. The First Soundmen (mixers) were beginning to see the writing on the wall, and at that point, began to distance themselves from both the IBEW and Local 695.

In early March, a group of about 125 mixers issued a statement that they were forming their own guild, along the lines of those of the cinematographers who had spearheaded the formation of the ASC into a bargaining unit, separate from the camera local. This new entity, the Society of Sound Engineers, Inc., would become the new bargaining unit for the mixers, separate from either Local 695 or the IBEW. By May, yet another organization was formed, under the moniker of the American Society of Sound Engineers, with Harold Smith (who had resigned as business agent of Local 695 in April) at the helm.

And so it went, with a new salvo in the dispute being launched almost weekly. IATSE was not going to quit without a fight. In early March, the President of the International, William C. Elliott, made a trip to Hollywood to assess the situation. According to reports at that time, Elliott’s goal was to reestablish the IATSE’s control over laboratory workers, prop men and projectionists, bringing them in under the Studio Basic Agreement. As the situation with cameramen, carpenters, soundmen and studio electricians was still in flux, he no doubt felt the best hope for reestablishing the ranks of IATSE workers in Hollywood was to focus on the crafts that were not open to jurisdictional battles yet to be sorted out by the A.F. of L.

Local 695 Rises Again

For reasons that are not immediately clear, by the end of June 1934, plans for the formation of both the American Society of Sound Engineers and the Society of Sound Engineers appear to have faltered. As of June 30, it was announced in Varietythat Harold Smith was once again helming Local 695, having been recalled by its members. Since the Local still had a few contracts to service with some of the independents, it may have been felt by the

members and Board that the soundmen had a better chance of survival if they stuck together, rather than risk a further fracturing their position by splitting some members into a guild (a plan which was not going well for the cinematographers).

It is illustrative to note the wage scale that was negotiated by the IBEW as of February 26, 1934. Note that the structure for mixers and technicians working on the lot was different for those on location. The six-hour basic rate was to satisfy a requirement imposed by the new NRA labor legislation, which called for a 35-hour week in an attempt to provide more jobs.

There was no limitation on the hours for those working on location, although the contract did stipulate that crews would be fed and housed at the studio’s expense. As a quick comparison, in 2010 dollars, this would equal about $400/day for a mixer, $299.00/day for recordists, and $225/day for boom and utility. Even with the recession raging, this was hardly anything to get excited about.

The Future

The battle between Local 695 and the IBEW would continue to rage late into 1935. Despite the hardships of the era, many of the members of 695 steadfastly refused to work under the wages and conditions as outlined by the IBEW contract. Both Local 695 and IBEW continued to petition Washington and the A.F. of L. to make a decision regarding jurisdiction, with no clear-cut mandate.

However, the International still had a few weapons they could wield in the fight, and by the end of 1935, they would put them to use.