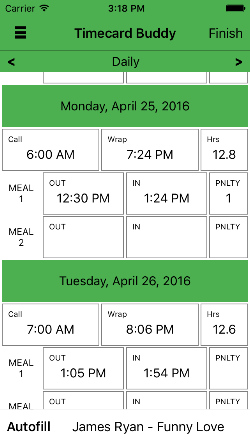

Young Workers Committee Report

by Eva Rismanforoush

In October of last year, Kavi Guppta, technology & workforce writer, published an article in Forbes magazine titled “Will Labor Unions Survive in the Era of Automation?” in which he interviewed Ilaria Armaroli, Ph.D. labor relations advisor at nonprofit think tank ADAPT. The article focuses on labor displacement due to machine learning and the mass computerization of the American workforce. The scope of this problem is widely researched, but it has been largely ignored by mainstream media, perhaps due to the lack of strategy development to navigate our economy, which will encounter mass unemployment within this century.

au·to·ma·tion

,ôde’mãSH(e)n/

noun: automation; plural noun: automations the use of largely automatic equipment in a system of manufacturing or other production process. “unemployment due to the spread of automation”

The fear of this unprecedented digital revolution has coined the term “Automation Anxiety.”

A White House study in 2010 suggested workers who earn under $20 an hour will face an eighty-three percent chance of job loss due to automation, while the population earning up to $40 an hour is at thirty-one percent risk. This study is already outdated.

Most research conducted in this area yields toward the In October of last year, Kavi Guppta, technology & workforce writer, published an article in Forbes magazine titled “Will Labor Unions Survive in the Era of Automation?” in which he interviewed Ilaria Armaroli, Ph.D. labor relations advisor at nonprofit think tank ADAPT. The article focuses on labor displacement due to machine learning and the mass computerization of the American workforce. The scope of this problem is widely researched, but it has been largely ignored by mainstream media, perhaps due to the lack of strategy development to navigate our economy, which will encounter mass unemployment within this century. displacement of low-skilled manufacturing work, but within this decade, machine learning has made signifi cant strides in the creative and cognitive realms that were until now, deemed as uniquely human.

Programmers now use deep-learning algorithms to prompt bots to teach themselves about their respective task. For example, a team at MIT released an artificial intelligence program in 2016 called the Nightmare Machine. It is a bot that has taught itself to generate imagery humans find scary or appalling. If you picked up a pop-culture or sports magazine in the last year, chances are, you have read an article written by a bot. Deep-learning algorithms have also been introduced to the medical field, such as IBM’s Watson, a program that practices patient diagnostics, and Enlitic’s X-ray analysis system, which holds a fifty percent greater accuracy outcome than radiologists and is currently being tested in over forty clinics throughout Australia.

Until now, it seemed automation only concerned the low-income population. But with this exponential growth in deeplearning & self-teaching algorithms, we need to start thinking about maintaining our standard of living, our benefits and wages, while adapting to emerging technologies. The bottom line is employers will always choose the most economic business model and we need to make sure it includes labor.

Whether your job is purely physical, creative or both, our union as a whole should adopt a strategy going forward.

WHAT IS AUTOMATION?

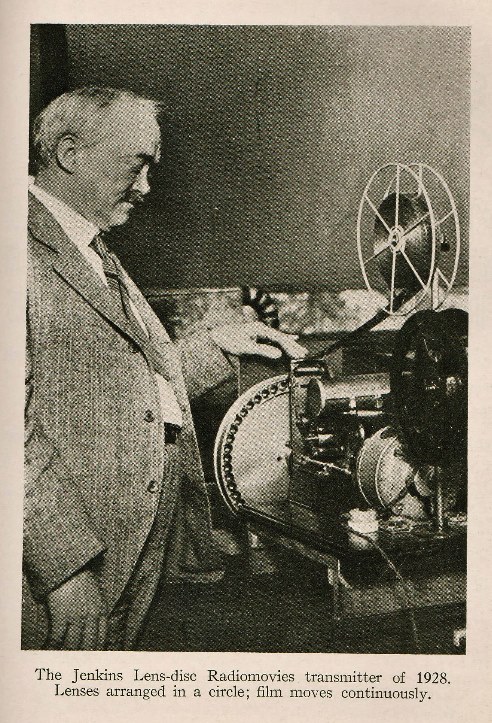

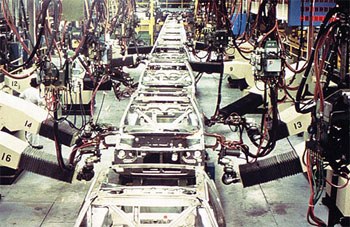

Automation is the technique of making a process or system operate automatically. This electronically controlled operation then takes the place of human labor. When we talk about automation, most people think about Michigan’s robotic car assembly lines as the absolute frontier. However, the first Unimate robot was commissioned in 1954 and installed at GM’s factory in 1961.

Today, robotic products and service bots encompass almost every aspect of our daily lives, from Bistro Cats Facial Recognition Feeders, self-parking cars, to the controversial call center ‘Chatbot’ Samantha West.

The automation of previous generations strictly dealt with the replacement of purely physical labor, but what we’re dealing with today is not only a creative, cognitive but an economic revolution.

HOW DOES IT AFFECT THE IA?

In 2013, Oxford scholars Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne published a study that rated the susceptibility of American jobs to autonomous computerization. The researchers applied a novel methodology to estimate the probability of 702 detailed professions. Having taken into account each occupation’s probability of automation, its wages and the educational background of workers, their findings estimate that forty-seven percent of the US labor market will be affected. According to Politifact and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, this number translates into more than seventy-three million American jobs.

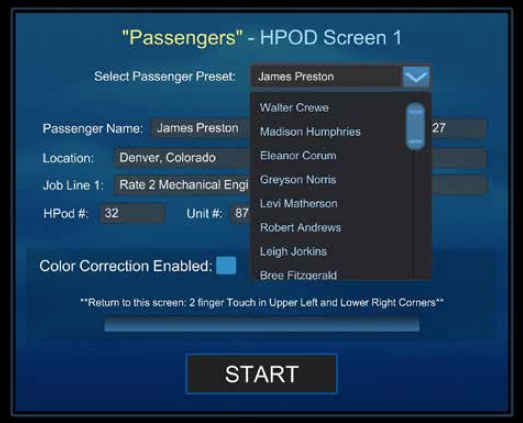

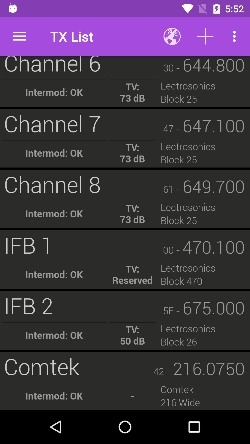

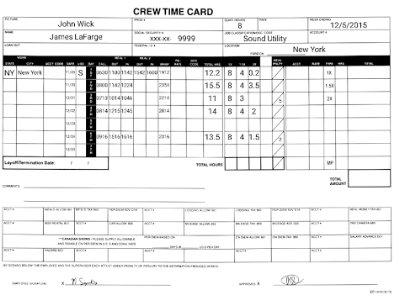

The film industry is still considered a small niche of the overall labor market, but Frey & Osborne state jobs in this sector will also be heavily affected by computerization. Camera operators face a sixty percent chance of work displacement in this century, while sound engineering jobs are rated at only thirteen percent risk. Broadcast engineers have a seventy- four percent chance of unemployment. Projectionists at ninety-four percent, riggers at eighty-nine percent and transportation at seventy-five percent are among the most at risk in our industry, while the probability of job loss for producers and directors lies only at 2.2 percent. Even within our own Local, there are stark contrasts although we all work side by side on set every day. With above-the-line job market practically safe, these numbers could also put the IA at a disadvantage going into future negotiations.

THE FISCAL IMPACT

“A tenth of the speed is still cost-effective at one hundredth of the price.” –Humans Need Not Apply

When given the choice, employers and investors will almost always choose the most economic option. An algorithm does not get tired, it doesn’t need a lunch break, a minimum turnaround, wages, weekends or health insurance.

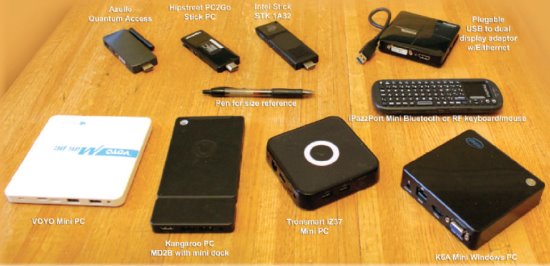

Many national television news studios like Fox News have already been completely automated by systems like the Vinten Radamec designs. What used to be a human camera crew of three to six people is now a one-person control room job.

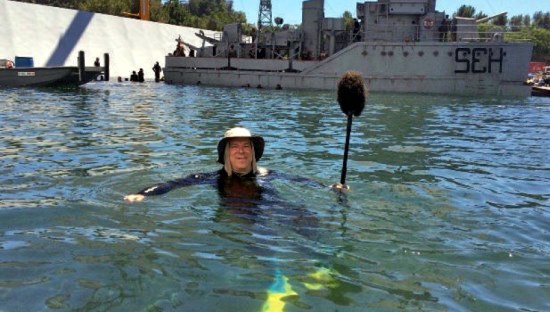

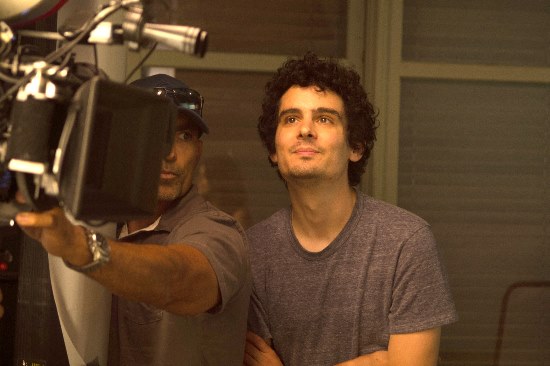

In the motion picture industry, robotic start-ups like Bot & Dolly have been providing systems like The Iris to automate camera movement sequences. It essentially reduces four jobs, the dolly grip, camera operator, 1st AC and 2nd AC into one position: one software engineer proficient in Maya Autodesk. Alfonso Cuarón used The Iris system for roughly sixty percent of his zero gravity shots in his Oscar-winning picture Gravity.

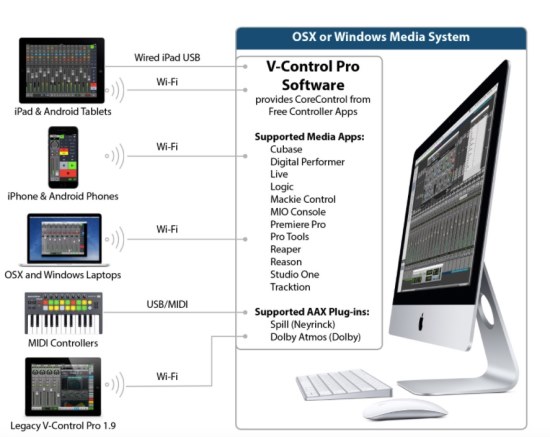

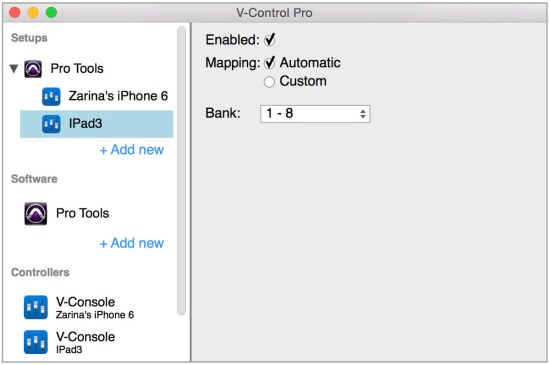

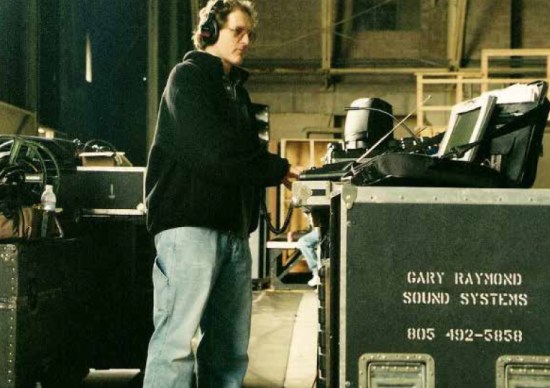

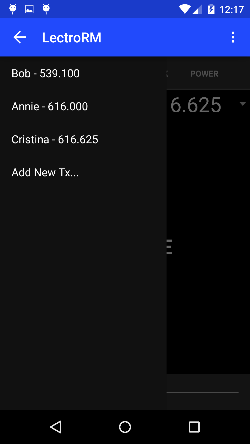

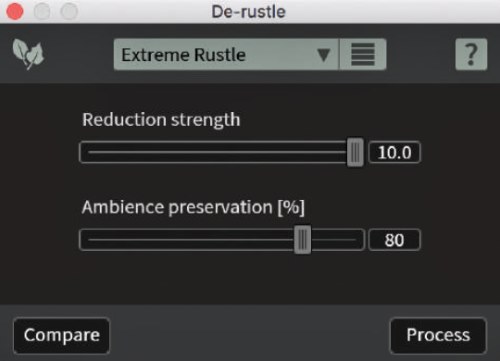

The sound community is starting to see deep-learning algorithms in programs like iZotope RX. This year, the release of RX6 included a deep-learning module called De-rustle, a plug-in aimed to restore dialog tracks from unwanted wardrobe noise captured by lavaliers.

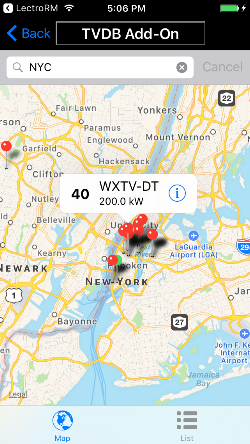

In broadcast, a vast amount of jobs are currently at risk due to facility centralization. Meaning, networks are consolidating individual TV stations into single major broadcast hubs to streamline operations and save costs, so remote stations can function with a smaller equipment investment and with reduced operational staff.

The central facility controls all network program reception, commercial insertion, master control, branding and presentation switching functions, and all monitoring. The hub facility then streams a ready-for-air signal to each of the stations in the centralization. Other than originating local news, the remote stations have few on-air functions. This kind of automation streamlines technical workflow and increases productivity, but dramatically reduces the need for union jobs.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

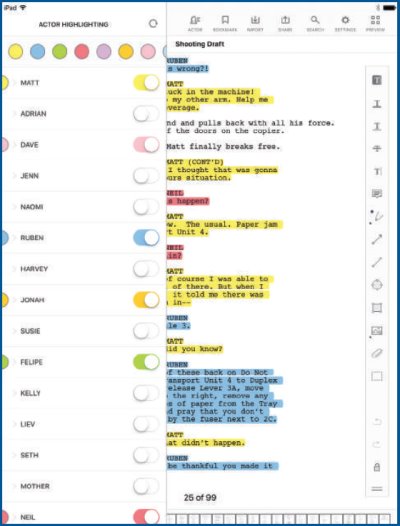

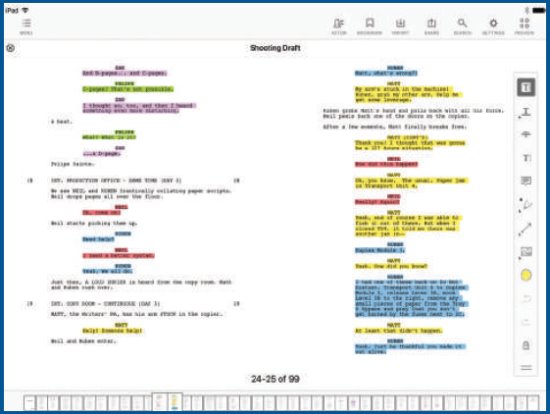

As a Local, the Education Director Laurence Abrams is already on the forefront teaching new software and technologies to our members. Within the last year, Local 695 offered classes such as the digital asset management & syncing course, virtual reality sound recording, fiber optic training, the future digital workflows for video engineers class and more. It is an excellent way to immediately adopt emerging technologies, keep jobs within our jurisdiction and remain relevant as the most skilled workforce in the entertainment industry.

Regarding broadcast engineering jobs, the Local 695 administration has been actively involved in talks with FOX Sports and the like to protect members affected by the centralization measures.

In terms of the IATSE as a political institution, Ilaria Armaroli suggests there is no “one best way” to deal with computerization, but unions must adapt their collective bargaining strategies to the changing labor market. And we have. Like our British sister entertainment union [BECTU], the IA has adopted the strength-in-numbers model by encouraging more young freelancers to join at an earlier age.

Armaroli also suggests researching the German law of co-determination. It is a legislature passed in Germany 1976. Codetermination or “Mitbestimmung” is the practice of workers of an enterprise having the right to vote for representatives on the Board of Directors in a company. “Workers’ participation in decision-making can provide an effective solution to this issue, allowing automation and digitization to become programs for success for both employers and employees.”

Conclusively, this report is not aimed to fuel the anxiety that surrounds this topic, but to encourage awareness and highlight the actions we’ve already taken as a labor union to place ourselves in a favorable position. So that we can proactively engage these issues on the local and federal level and prevent being blindsided in the years to come.

REFERENCES

Guppta, Kavi. “Will Labor Unions Survive in the Era of Automation?” Forbes. Forbes magazine, 12 Oct. 2016. Web. 08 July 2017.

Morgenstern, Michael. “Automation and Anxiety.” The Economist.

The Economist Newspaper, 25 June 2016. Web. 08 July 2017. Humans Need Not Apply. Dir. CGP Grey. Perf. CGP Grey. N.p., 13 Aug. 2014. Web. 08 July 2017.

Berger, Bennet, and Elena Vaccarino. “Codetermination in Germany – a Role Model for the UK and the US?” Bruegel. Bruegel, 13 Oct. 2016. Web. 08 July 2017.

Frey, Carl Benedikt, and Michael A. Osborne. The Future of Unemployment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerization? (n.d.): n. pag. University of Oxford. Oxford Martin School, 17 Sept. 2013. Web. 8 July 2017.

“Industrial Robot History.” Industrial Robots. Robot Worx – A Scott Company, n.d. Web. 08 July 2017.

Pescovitz, David. “Bot & Dolly and the Rise of Creative Robots.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 20 Mar. 2014. Web. 08 July 2017.

Proulx, Michel. “Centralized and Distributed Broadcasting.” TV Technology. New Bay Media, 1 Feb. 2003. Web. 08 July 2017.

“What Is Automation?” ISA. International Standard for Automation, 2012. Web. 08 July 2017.

“Current Employment Statistics.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, June 2017. Web. 08 July 2017.

Harari, Yuval Noah. “Universal Basic Income Is Neither Universal Nor Basic.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 04 June 2017. Web. 09 July 2017.