MY GODLIKE REPUTATION PART 2

(A tutorial for those without half a century in the business, and a few with)

by Jim Tanenbaum CAS

I consider my ultimate loyalty to be to the project, to make it the best movie possible, so my always getting the best sound possible is subordinated to working as quickly as I can with the minimum impingement on the other departments, so long as I get sound that is at least “good enough.” Of course, my idea of “good enough” is pretty damn good, but not perfect.

What is “good enough”? For starters, remember that production dialog will be put through a dialog EQ: rolling off the bottom end and cutting off the top at 8 KHz (or for some upscale mixes, at 10 KHz or even 12 KHz). And unfortunately, the dialog will often be buried under the music and effects. (I defy most production mixers to distinguish between a Sennheiser and a Neumann on the release track under these conditions.)

The director, editor, and producer have heard the actors’ lines hundreds or thousands of times in post production, and it has become permanently imbedded in their brains. They can still hear it even when the dialog track is completely muted. The re-recording mixers will try to push the dialog levels, but they are often overridden by the higher-ups, especially for dialog following the punchline of a joke. (I think it would help to have a laugh track to play on the dubbing stage at the appropriate times.)

I try to get my “good enough” production sound through to the release print in spite of this.

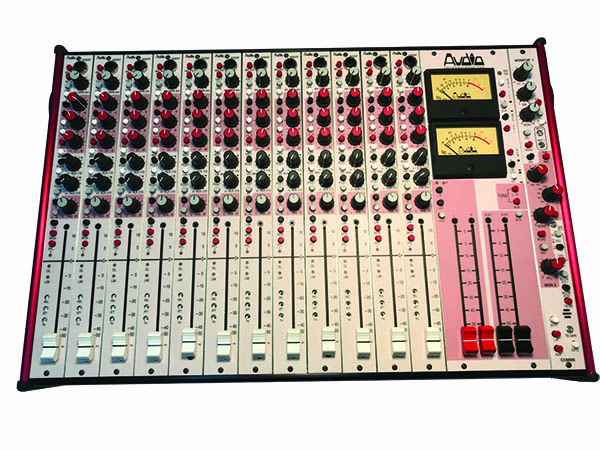

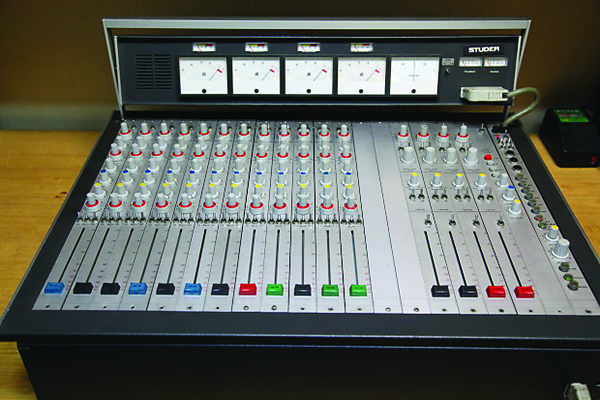

To avoid holding up production, I bought a second Nagra IV for a spare as soon as I could afford it, and also a Nagra QFC cross-feed coupler, which mated the two recorders so they could record identical tracks, and use all four mike inputs and the two line inputs.

Since the 7”-reel lid adapters weren’t available way back then, this helped me tremendously in dealing with the 15-minute runtime at 7½ IPS of the 5” tape reels. When I got near the end of the first reel, I just started the second machine to give some overlap, and then reloaded the first Nagra at my leisure. Unfortunately, calling for a tail slate caused too much confusion, so I had to note the overlap on sound reports and depend on the transfer house to handle the splicing. More unfortunately, the quarter-frame resolution of the magstripe sometimes caused a glitch at the splice, so I used the 2-recorder overlap only when absolutely necessary.

Now that “running out of tape” is no more, I still avoid production delays by having my bag rig ready to go for car shots between stage setups. And the disaster of losing a recorded ¼”-tape is also a thing of the past, but I always put the day’s flash-memory card in a DVD case, along with the sound report, and make sure not to reuse my primary CF cards until well after shooting is finished.

One of the “10 Holy Truths” I teach my UCLA students is: The most important thing experience teaches you is what you can get away with, and what you can’t. And you usually have to make this decision instantly.

Many years ago, I was on a commercial with the late Leonard Nimoy as spokesperson, and he was justifiably annoyed with the production company for their many screw-ups, such as the car with no air conditioning that that picked him up for the 3-hour ride to the location. My boom operator had to work very hard to get a quiet mounting for the radio mike, since his wardrobe was 100% polyester, including the necktie. The rehearsals were fine, so Leonard went back to his motor home to await the “magic hour” for shooting.

Magic hour arrived, but Leonard didn’t. As the light was fading, he finally showed up, not in the best of moods, as the A/C in his motor home wasn’t working very well either. He was hustled into position on the set and the director yelled “Roll!” As the dialog started, so did the clothes rustle, on every fourth or fifth word—definitely unusable. My experience told me that he had messed with his tie while away from the set, and it will take a complete rip-out and re-rig to fix—at least two to three minutes of the at-most ten minutes of usable light remaining.

The director was one of my regulars, very talented, but stern and disdainful of incompetence. Fortunately, he trusted me. Unfortunately, he trusted me to the point that he wasn’t wearing headphones because he needed to listen to one of the clients during the shot. I immediately got up, during the take, and told him the sound was N.G. and I needed two minutes to fix it. He wasn’t pleased with the news, but called “Cut!”

I headed directly for Leonard, because I had already taken the necessary items with me before I left my cart. I re-rigged the lav in a minute-and-a-half, and put the Nagra into “Record” even before I sat back down in my chair. Because of the crucial nature of the situation, I knew it would not look good if I merely sent in my boom op, even though they could handle the problem as well as I (or perhaps even better). Seeing me dealing with the lav, my boom op had automatically brought a Comtek to the director, but he waved him away.

After the sun set, the director went to video village to review the takes, and I stood quietly behind him. The clients were happy, and thus so was he. A few minutes later, I approached him to offer an explanation. He smiled and said, “Nimoy f’d up your mike in his motor home, didn’t he.” It wasn’t a question.

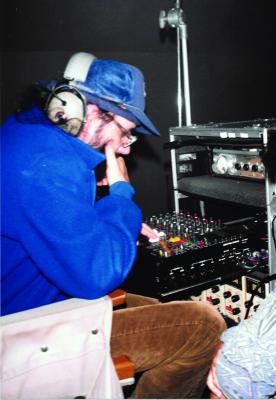

Here is the flowchart I use to deal with problems on the set:

The other side of the ¼-inch tape is that sometimes (okay, rarely), the re-recoding mixers will mess up my tracks. To help guard against this, I have found that if I ride the gain properly, they will tend to leave my tracks alone and pay more attention to the music and effects tracks instead.

The two areas to which I pay special attention are: 1, matching background ambience from take to take and between different angles of a scene, and 2, limiting the total dynamic range of the dialog.

Having the ambience not jump on picture cuts follows another one of my 10 Holy Truths: Sound that calls attention to itself has failed. Raising low-level dialog and reducing high-level dialog (manually—I don’t like the sound of limiters or compressors) means that the re-recording mixers won’t have to do it themselves. However, these two factors are interrelated—simply raising or lowering the recording-channel gain to adjust dialog levels will affect the ambience the same way.

Describing all the various methods to control dialog levels without changing the ambience is beyond the scope of this article, but a very common one is to simply move the mike closer or farther from the actor without changing its orientation. On a soundstage or non-reverberant exterior, the mike’s distance can usually be altered about 3:1 without noticeably affecting the perspective of the dialog while giving almost a 20-dB dialog gain change. Since the distance to the source(s) of the background noise will not be changed significantly, the ambience will not change either, as long as the mike’s orientation with respect to the source of the ambience is not changed while it is being moved closer or farther from the actor.

While I just said my ultimate loyalty is to the picture—in typical Hollywood fashion that’s a lie. My first loyalty is to myself, my life, and limb. During car stunts, I always mix standing up, with my chair out of the way, and have located all the escape routes in advance. However, on one show, this wasn’t enough.

Working on the TBS back lot, there was a scene where a tractor-trailer careens around a corner and takes out a curb mailbox. With my physics background, I set up the cart in a safe place should the truck skid off the street. Then the 1st AD told me that it was the worst place to be, and insisted I move to a location he selected. I knew better than to try teaching him Physics 101 about centrifugal “force,” and did as he said. On the first take, the truck lost control and headed directly for me, or rather where I had just been standing. Unfortunately, the escape path I had chosen was also picked by a lot of the crew, and we were all jammed together and stuck there. Fortunately, the driver got the vehicle stopped in time. Unfortunately, it also came up just short of the sound cart. (It was WB Studio equipment.)

On a night shoot, we had completely blocked off a street with barricades, flashing red lights, and had police traffic control. A speeding drunk driver plowed though all the barriers, and only that he then T-boned a police car parked crosswise in the street kept many of us from being killed or maimed.

You are never absolutely safe anywhere, but especially on a movie set. Fire can spread amazingly fast. Safety chains on effects shots can snap. Remember that when you are tempted to “get a good view” of something being blown up.

Even on an “ordinary” shoot, you need to maintain cautious work habits, but more importantly, be aware of your surroundings. Coming back from lunch, I was in a line of people entering the stage, but was I the only one to get a faint whiff of natural gas? Apparently so. I immediately notified the 1st AD, who was not overjoyed at the news, but (properly) followed me outside to verify it, evacuated the building, and called the gas company. When they arrived, they found a cracked meter, and replaced it. But because I don’t trust anyone (including myself), the next morning I went straight to the meter and … still smelled gas, even more strongly. The AD didn’t even bother to check, just got everyone out and called the company back. The main gas line had split from the stress after it was re-attached and checked for leaks.

Even when the director or AD wants you or your crew to “hurry”—don’t run. Not only are you more likely to trip or have an accident, but they will eventually expect you to move that fast all the time. Save the running for a real need, like losing the light on a magic-hour shot.

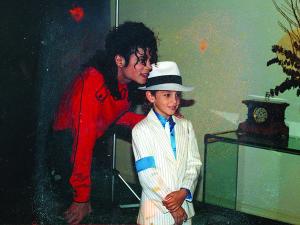

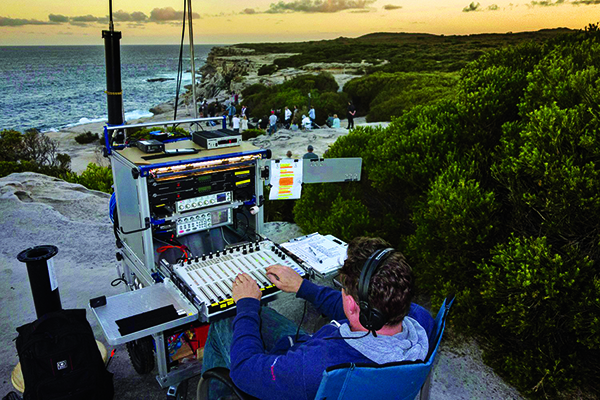

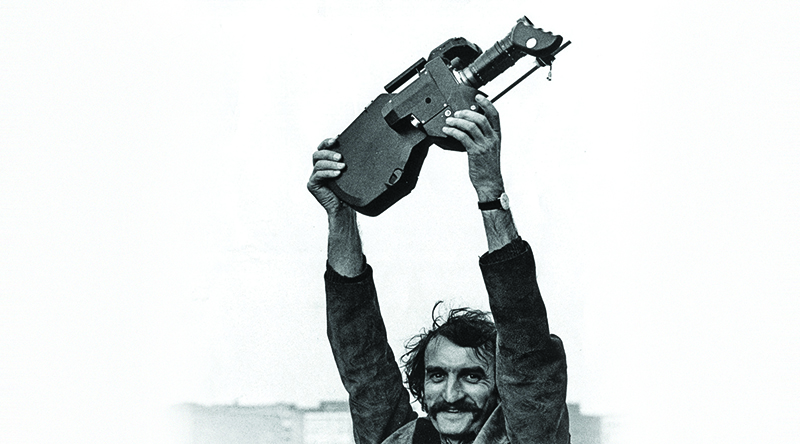

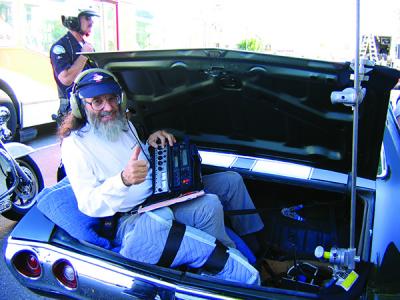

Whatever you may have heard about grips’ “Sex, Drugs, and Rock & Roll” mentality, I have found most of them to be very knowledgeable about safety, and trust their judgement. (The pix shows me only part-way rigged: a pad for my left knee and more safety straps were added before leaving with the police escort.)

Finally, there is a very real possibility that you may have to choose between your job and your life. I was working a nonunion feature in a small town in another state. Yesterday had been 18 hours, and I had already worked 10 today when the producer showed up and said that at wrap, some 2 or 3 hours hence, the company will have 3 hours to pack up and check out of the hotel, and then drive our own cars another 2 hours, at night on unlit mountain roads, to the next town on the schedule. When we get there, some more shooting will be done before dawn. (God bless the I.A.T.S.E. and other unions for protecting workers’ lives.)

I went to the 1st AD, and politely explained that I and my boom operator are too tired and sleepy to drive safely, and must have a proper night’s rest before leaving. The AD replied that the company must be out of the hotel by a certain time, and that there is nothing he can do.

“There is something you can do,” I told him, “hire a new sound crew, because after this scene, Jean and I are going back to the hotel to sleep, and we’re driving back to LA tomorrow.”

The producer left the set, but returned half an hour later to announce that we would be staying in the hotel there that night after all, and not leaving until the next day.

The UPM who had hired me was one of my regulars, and very happy he could make me the bad guy (and keep anyone from getting killed on his watch), and continued to hire me for other shows (read on).

While not quite as important as safety, comfort is a serious concern. If I’m sitting out in the hot sun, or shivering in the cold, I know I’m not doing the best work I could. Learning how to deal with temperature extremes is just as important as learning about audio. I have never regretted the many hundreds of dollars I’ve spent on specialized cold-weather gear. There’s no such thing as a really warm glove—the secret is down hunting mittens worn over thin glove liners. The mitten has a slit on the underside for extending fingers to (fire the rifle) work the mixer pots, then pull them back inside.

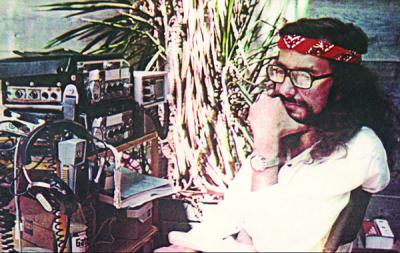

Hot weather requires light-colored 100% cotton clothing with long sleeves and pant legs to absorb perspiration and cool you as it evaporates. Sweat that drips on the ground cools only it. Note that I have clipped a space blanket to the top of my umbrella to completely block the sunlight.

There’s another kind of comfort that’s important, too—emotional comfort. Early in my career, I put up with a lot of sh*t because I needed lines on my resume, but as soon as I got “enough” of them, I decided that what I didn’t need was a heart attack or a perforated ulcer.

On a nonunion shoot, the first day of shooting was a disaster, and we didn’t finish the scheduled work. At the end of the day, the a** hole director called each crew member “on the carpet,” in front of everyone else. (God bless the I.A.T.S.E. and other unions for protecting workers from this sort of abuse.)

When my turn came, I got: “Tanenbaum, you’re completely unprofessional. We had to wait half an hour for you to put a radio mike on the actor.”

I calmly replied, “Kenny was standing outside the actor’s motor home, but the doctor wouldn’t let him in until he finished sewing up the actor’s hand. I’m sorry that’s not professional enough for you, Sir. Would you like me to leave now, or stay on until you can bring in a replacement professional mixer?”

The UPM I just mentioned, was standing on the sideline and frantically motioning me to shut up, as he didn’t want to lose me, or a day’s production while they were getting a replacement sound crew and equipment.

The director backed down, moved on to the next victim, and left me alone for the rest of the shoot, even when I didn’t notice that I had run out of tape halfway through the only take of a shot until we had moved to the next location. (I had to work that day with the flu and a 103° fever.)

Text and pictures ©2019 by James Tanenbaum, all rights reserved.

Editors’ note: Part 3 of 3 continues in the fall edition.