A Conversation with Mark Ulano

What was it like working for an iconic director like Martin Scorsese?

Well, first and foremost, filmmaking is my religion. I was born and grew up in New York City. My coming of age as a filmmaker was in the late ’60s, early ’70, and Martin Scorsese’s emergence into the iconography of cinema was at its beginnings then, so working with him now has been very significant for me. I believe he was an adjunct teacher under Haig Manoogian at NYU in those days. Haig really created the NYU film school, which eventually has become one of the giant places of learning for cinema and for emerging filmmakers. This was at a time when film school was really looked down upon in Hollywood, and even the New York community as an affectation. It’s very different now. Marty’s scholarship, then and now, and all the time in between, speaks to a very important part of my life.

To be asked to join the very evolved community around Marty at this point, and on this particular project is one of the high points of my career and my life, so it was very special. I consider it a profound privilege for the actual engagement, the sense of community it provides, and for the work itself. I think this film is a work of substance that will stand on its own indefinitely, a very rare thing. I’ve been blessed in this regard with various directors, but Marty is … well, if I had a string of pearls, he could be considered one of the most special gems. I’m very, very glad that at this stage of my life and career that we had the chance to work together. To partner with his family team, Tom Fleischman, his Re-recording Mixer, oh my God, thirty years with Marty, and Thelma Schoonmaker, sixty years working with Marty in the editing room, since Woodstock, the movie, and through all of the other films, that partnering. To be invited inside the secret halls of that friendship, to contribute day-by-day, it doesn’t get better.

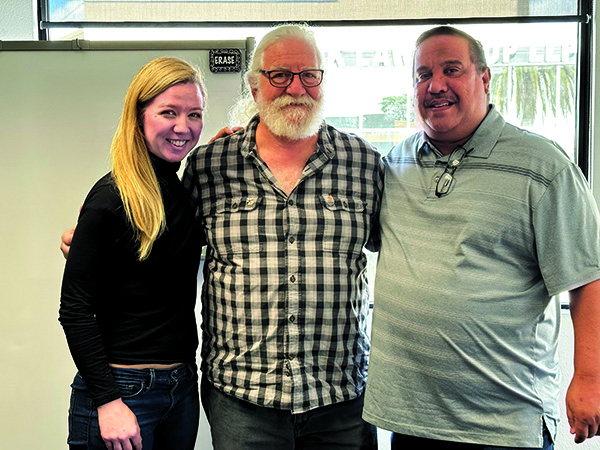

You share your work with John Pritchett.

Absolutely. John was originally brought on to do the show through the Producer, Daniel Lupi, who I’ve also worked with in the past, and the same with the First AD, Adam Sumner. John had to leave the show very early on for personal reasons unrelated to the film and I was asked to come in. Obviously, this prevented my normal preparation. I was diving into a group of super professionals at the AAA list level. I’ve done that before. The DP and I, who I admire enormously, Rodrigo Prieto, the Gaffer, Ian Kincaid, many people in the crew, above and below the line, were people with whom I had creative work history. I got to overlap slightly with John’s last day of production. It was on a Friday, and I was taking over on a Monday, and we were together that whole weekend, me prepping my gear and my team. John was characteristically generous about helping me get in alignment with the show. If I had questions regarding continuity, we collaborated.

My friendship and experience with John actually began forty years prior, when I was asked to do a Robert Altman movie. John was not available, and he walked me through the setup in 1987 which was ½” reel to reel Otari 8-track. In my opinion, John Pritchett is one of the giants in our field. He’s had one of the most iconic careers in production sound. John’s history has been an amazing balance of the high-end tentpole projects, and the purposeful, passionate, independent art side of the work.

My team included Doug Shamburger, Patrushkha Mierzwa and Nick Ronzio, Brandon Loulias and Gary Raymond. All contributed enormously and knew we were on a special project with a special film family.

When you’re called on to be in a circumstance at the highest level, it’s like going to the summit. Marty has enormous vitality, he has enormous respect for the content of his projects. He worked for a very extended time in preproduction building trust with the Osage Nation, including them in the run up to the work and their participation both at the concept, the emotion, the story level, and physically in the film. Many descendants of this event, these tragedies are participants in front of and behind the camera.

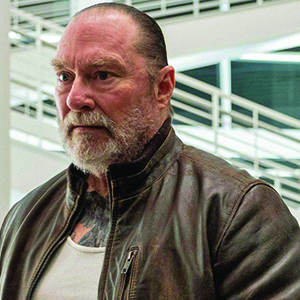

The Osage community that exists today, that emerged from these tragedies from the 1920s, represents a unique piece of American history. All the parties seem to have a great sense of appreciation for the respect shown in telling this story. Key creative relationships contributed to this journey. Robert De Niro and Marty have done ten films together. Leo and Marty have done seven. Combined with this ensemble, Lily Gladstone, John Lithgow, Brendan Fraser, Charlie Musselwhite, the list goes on. Everyone wanted to come and be a part of this film, and to join a seasoned filmmaker like Martin Scorsese in full possession of his powers, up close and personal, shot by shot through COVID and 108 degree in-the-shade weather, never flagging. It was rockin’ man. It was just rockin’.

Killers of the Flower Moon was filmed in Oklahoma.

We based out of a town called Bartlesville, which is the central town of the Phillips Oil Company and has a lot of Oklahoma history in terms of its oil wealth. In fact, there is a very significant Frank Lloyd Wright building there that is in the middle of this prairie universe that is beloved and well cared for. Bartlesville is about thirty miles out of the towns where these tragedies took place. Killers of the Flower Moon is the title of David Grann’s nonfiction book that was published in 2017. The book takes a deep dive into the events that this film is based on.

We filmed in the real places where these events took place, where these conspiracies and murders were hatched and executed by this community toward the Osage Nation. They turned the town back into the 1920s, they hauled in tons of dirt to return the paved town roads back to the period of the murders. We used an avalanche of ’20s period vehicles and horses for the background crosses. Basically, we time traveled to the early 1920s Oklahoma and everything around you was of that era, all the production design, costume design, etc., were lovingly created in great detail to evoke the period and bathe the cast in that special environment. We were forty-five miles from Tulsa, where almost simultaneously, the Black Wall Street tragedy was taking place. The two tragedies are unrelated in terms of individuals and shared conspiracy but are connected by the endemic racism in the local community, and the hostility toward the successful progression of people of color.

In Tulsa, it had to do with an emerging affluent, African American community. In Osage County and Washington County, counties that were inside the Osage Reservation, the members of the Osage Nation were per capita, the wealthiest humans on the planet Earth due to the oil wealth that befell them as a community. The first stages of the emerging toxic racism appeared when the local white community successfully lobbied governmental entities to create a corrupt gatekeeper system of the wealth of the Osage members. They were declared legally incompetent to manage their own financial affairs and had to self-declare, “I am incompetent.” Each time they would come before these attorneys, or local business people who decided whether or not they could spend their money the way they wanted to, they were told that they had no legitimate authority.

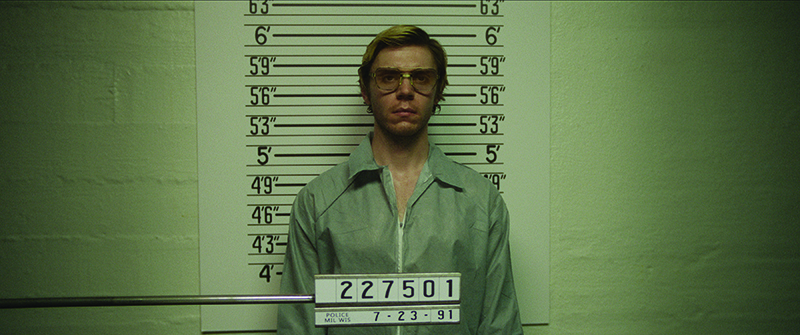

Then came the larger conspiracy, which is centered around the notion of marrying the Osage women. Men were marrying the women and then murdering them, their siblings, their parents, their children, to acquire and concentrate the mineral rights or the head rights of the oil wealth. The conspiracy’s leader is the character played by Robert De Niro, based on a real person, William Hale. Hale used his acquired fluency in the Osage language to gain the trust of the community as the prime liaison with the white community. The vocal tonality employed by Robert De Niro for his character becomes a tool for deception. His nephew, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, is ultimately a conflicted henchman torn between his love of his wife and family and fear and greed enveloping him in his uncle’s conspiracy. There were over two hundred murders, primarily people in their mid-to-late 20s, and only a very few were investigated.

To this day, there’s controversy over the roles played by all the parties, but the facts are indisputable. Being in those actual places, in those rooms, in those buildings, in the physical space of where these things happened, created a kind of special energy that you don’t often experience on a film. It tore away some of the artifice, creating a sense of authenticity for this story. There were moments that were moving from fiction into reality and back, that were almost surreal.

The mindset was Indians were lower than dogs, and you could murder them without worry of any consequence. They went to the President of the United States to get help, and that’s how the early FBI got brought into this situation. We filmed in those places where it happened, it was kind of spooky. The only other time I’ve had this kind of experience was on Inglourious Basterds where we were shooting in the Vermacht headquarters in rooms where Hitler and Goebbels and others walked the floor of the rooms with all of the power and insanity at their disposal. This was similar in a certain way.

What is Marty’s style in terms of the way he shoots and how did that impact your work?

Well, when you have a great conductor, composer, and leadership of an orchestra, the first order of business, usually for those who have risen above the rest, is that they bring a community, an ensemble around them of like-minded artists who will come and contribute at the maximum level of their capacity without reservation. 150% all in for the entire tour of duty. That’s his history, and that’s his methodology. He’s old school, and I mean that in the most respectful and appreciative way, because it’s not common. He understands the power of a director is through delegation to advocates who understand his intent and execute that intent flawlessly in concert with the other disciplines adjacent. When that happens, your percentages of achieving a magic above the mundane are greatly increased. Rodrigo Prieto, as a filmmaker contributes, he’s a cinematographer who is always about serving the project, not about serving territory. It shows in his body of work. Marty’s the same, he limits his communications in terms of the obvious and is generous in his communications in terms of the choice of options before him. Knowing the difference between these two is a joy to witness in the day-by-day, shot-by-shot process. It just warms my heart.

His process is completely focused. What are we doing? What is this shot? Where are we in the moment of the moments of this shot where the camera should be for emphasis. All of the other elements are tied to that idea of the grammar in place. It’s not, “Let’s get a bunch of stuff and then figure it out later.” It’s, “What do we need the audience to be experiencing at this moment and be around that realization all day long?” So, he does, and he expects everyone around him to have that already as part of their tool set. You have to be up to that game. You have to have that fluency in your work. My sense is that if you are not, and he knows it, you lean, I would suspect more toward disappointment than anger because he’s invited you into his house and you’re a guest in his house. “Please, I love the most that you can do, please bring that to this project because this project matters.”

With your long work history with Quentin Tarantino, is there any similarity or are there differences between Quentin and Marty?

Great similarity in this piece, in the predisposition to do the homework in advance of coming to the day. They’re both absolute students, perpetual students of cinema. That’s not a static thing. They haven’t packed up two pounds of film knowledge and figured they’re on their way. Every day they’re still learning by what we’re doing in the day, and they’re still learning at night because they’re watching everybody else’s contribution in the work. They’re archivists, they’re historians, they’re passionate about, “How do I best do my piece? How do I maintain my fluency as a filmmaker through the work? How much can I learn by the work of others?” So, there’s a great commonality. Also, their day-to-day shot approach. They don’t micromanage. They manage from above, they don’t waste their resources on second guessing. They made that investment in the people they chose to bring around them in the first place. And that frees that energy to be where it needs to be.

How about your crew?

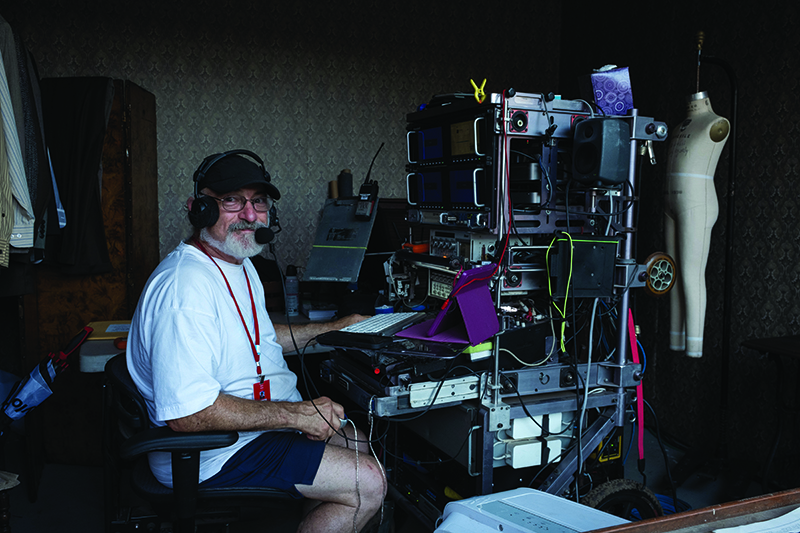

We discussed the transition that I took over the show very early on. With minimal to zero prep, but had the good fortune of having had many pre-existing relationships with key departments, in particular, the entourages of Leonardo and even Bob De Niro, but also the Director of Photography, the Gaffer, the First AD and others were people that I had had done deep intensive projects with in the past, the Line Producer, etcetera. Also having a very healthy friend relationship with John Pritchett, who was gracious and helpful in the transition. My usual long-standing professional marriage with Tom Hartig as my colleague and Boom Operator since 1999, and Patrushkha Mierzwa, also Boom Operator colleague and alternating UST since 1982 or ’81. Tom was unavailable, he was involved in another project, this came up rather suddenly. He was committed to me for the following project, which was the Whitney Houston film, but he wasn’t available for the sudden arrival of the Scorsese project. So, I got very fortunate, I reached out to Doug Shamburger, who is one of the greats. He’s boom royalty who has a long, long history with many of the best mixers. Most recently, with Willie Burton on Oppenheimer. Doug and I have been trying to work together for literally fifteen years, twenty years. When I would call him, he’s not available, when he’d call me. I’d already be under way with my regular team.

It was kind of a running joke for us for years, and we’re friends socially, he and his wife and Patrushkha and I. But he was available, coming off another show, there was a slight overlap, he worked that out because it was another Apple show, and Apple was also in support of Marty. So, Doug was in, and came to Oklahoma. Patrushkha was not available for the beginning of the show. She helped with the run up and the transition, but had other commitments initially. Nick Ronzio, who’s fantastic, came on as our UST, Utility Sound Technician, and so I had this amazing team of Doug and Nick to start and to get us going, hitting the ground running.

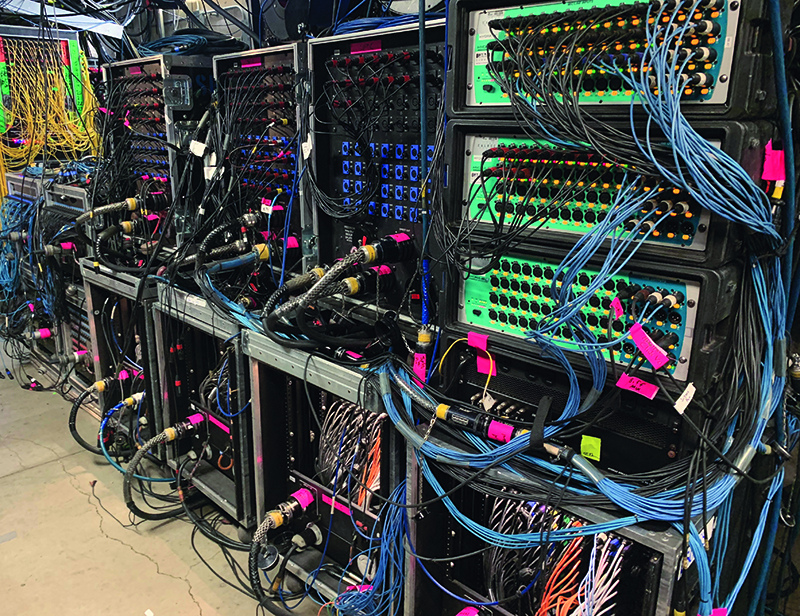

The tricky part was they were not immediately familiar with my packages, my regular crew was, but the compensating part was they’re both such bulletproof hardcore veterans that didn’t matter in the least. They immediately were right at speed, which was great. Nick had a limited availability, so this was a bit of a patch work, which is really unusual for me, but he stayed on for, I think approximately the first 40% of the show, something like that. Patrushkha was still not available, so we had Brandon Loulias.

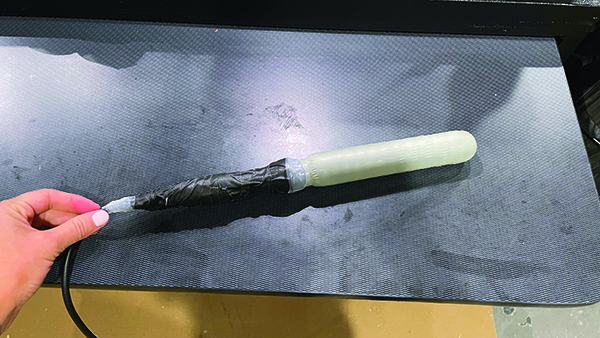

Brandon came on to be the interim third until Patrushkha could break free and come and do the rest of the show. Brandon worked his butt off and was also an important contributing factor. One of his special skills was his knowledge of electronics, his engineering knowledge of Yamaha gear. That came in very handy because some of the environments we were in were particularly unfriendly to that gear. Although I have redundancy, there were moments where we needed to tear something apart, and Brandon had a skill set that could take care of that in the field.

Then Patrushkha came on, completing the team. She also had prior relationships with other crew members like the Gaffer and others that were forty-year friends and working relationships. Ian Kincaid, a shout out to one of the most brilliant artists in the film world as a Gaffer. Our department is not a vertical hierarchy, we all share very different but overlapping responsibilities, and I look at us as a jazz trio if you will, or jazz quartet, depending on the situation.

We had a local trainee from the Oklahoma community, John Martinez, who continued from the week or two that he had with John Prichett’s crew, and that was very, very helpful. He worked very hard, he had excellent social skills, and was a quick learner. We needed that because of the physical geography and the environment, the weather and relentless heat, dust and assaulting factors, all pushing us to our better selves.

Was there music playback?

We had playback. Gary Raymond came and did several playback scenes for us that were very important. We had a giant scene with a huge body count of extras. It was an evening, with a large band. We also had a wedding sequence that Gary did for us that was intertwined with dialog, dancing, giant crane shots, and music playback.

Was there any live recording of music?

There was a little bit on a piano. There was a little bit at the wedding party. There was a thing with a guy with a guitar, which I don’t think made it into the film. They did a bit of additional material in New York with Tod Maitland, who had worked with Marty in the past, so there was a very good established relationship. Tod did that additional material. It’s the 1930s radio show, that was Tod’s work. They did a live recap with Marty cameoing in the scene, which is fun, kind of a delicious button, really. It’s a surprise. Tod did another couple of days of pickups in Oklahoma, much later in the year.

Was that the final coda?

The final coda was the high angle shot, with hundreds of extras. This is a big film, it’s an epic film, and structurally, very akin to a Bolero, a climbing crescendo in plot, character arc and musicality. Robbie Robertson’s final film score, sparce and percussive is the ideal cohort to the film’s other elements.

This was my fourth film with Leonardo, and my second with Bob De Niro. Those prior relationships, particularly with Leo, created an immediate environment of trust. Leo, in his generosity, basically introduced me to Marty on set in front of others, which doesn’t always happen with a huge warm embrace and a, “Yeah, we just started right now.” So that was a good thing.

Were they all practical locations or was there some stage work?

The radio show in New York was stage work. We had some stage work that was done in airplane hangars. They built sets that were repeats of some of the actual practical exterior locations. So it was a blend, I would put it at about 80/20 practicals to stage work, maybe 70/30.

During the production, it was also the 40th anniversary of Raging Bull, and so for the Tribeca Film Festival, which is Bob De Niro’s baby. They set up a live streaming interview with Leonardo as the moderator interviewing Bob De Niro and Marty, to reflect on their journey together making Raging Bull. Marty could have done stand-up as an alternate career. He was hilarious, and the auditorium was absolutely packed to the gills, but it was being sent back to New York live streaming for the Tribeca event. There was a lot of good-will and good humor involved.

There was a fair number of driving sequences with period vehicles.

Along with that factor, there was a tendency to have frequent background crosses with period vehicles at full bore. I did engage passionately with our picture car department, because every time we were in the town or anywhere, that was always a visual code for the period. We incorporated spark suppression when possible. Can we get the quietest versions, working with the ADs, so that their choreography of a vehicle passing during a dialog scene wasn’t during the most intimate and significant information being said? It required an enormous amount of cooperation on the part of many people, primarily the production, AD department, and my team with Transpo. We worked it out shot by shot.

And they accommodated you?

Certainly, most of the time. If we were at a point where the scene’s information and the character revelation were at true risk and the threshold had been crossed, we’d engage in refining the coordinated timing. My threshold of concern, generally, is if there’s a competing element breaking the connection between the characters and the audience. You don’t want discordant, anachronistic sounds that disrupt the flow. But if it doesn’t break my threshold, if it doesn’t break the connection between the characters and the audience, and is functional in terms of how it can be handled editorially later, then we’re in the zone. That’s a moving target as we have more and more post-production tools that allow us to legitimately, through algorithms, separate certain elements after the fact that would, in the past, to be intrinsically married. But I also know that if you don’t become a student of that closely, you can make problematic assumptions about how much that can be applied.

If we go to the heart of the movie itself, the fundamental motivation of making the movie has a kind of purity to it, a social relevance. Not a bleeding-heart version but a just version of that. This was a stark indisputable, complex, profoundly racist event that took place in the 20th century in the American culture. The duality of the rights of man and the lack of perception that certain communities did not get recognized as full human beings is deeply explored. It was an extension of the Dred Scott decision in the 1800s that helped set the table for the Civil War. You’re looking at this whole community that conspired, in multiple murders, around the idea that the Indian Nation was less than human and non-deserving of what they acquired. They had been forced away from their native homeland into un-arable terrible property which they had the foresight to purchase inclusive of the mineral rights and ironically turned out to be the wealthiest oil strike in American history, twenty years hence.

The oil wealth led the Osage to live like wealthy white Americans.

Before they got their arms around the Osage Nation as a group, and had many of them legally declared incompetent to manage their own money, they had lived the way any one of those in the white culture would have themselves. Yes, they had the most Pierce-Arrows in the United States in one place, they bought furs, they sent their kids to European universities. Wouldn’t you? They had achieved a kind of cultural iconography of wealth in the 1920s, that was in parity to what wealthy Americans did in the 1920s. That just enraged the locals. They had multiple pricing schemes for the Indians who would pay ten, fifteen, twenty-five times for the same groceries and sundry products. It was brutal. Even so, the Osage took it all in stride, philosophically, un-materialistic, generous to a fault, carrying themselves with great dignity.

There are certain emotional and creative takeaways I had from this project that I think are significant. One is, Marty and company are among the few places where the tradition of stories that matter, being done with authenticity and integrity, can survive the gauntlet of interference that the industry provides frequently. It’s too rare, but it’s also an example of the possibility. When you are invited to enjoy the privilege of participating in that kind of environment, you can, and I did, have a spirit reward of being in the elevated place of the purity of intent.

It was a subject that had deep roots in significant issues that resonate beyond its own time, being done with the maximum integrity possible by great artists in their work. We were part of that. That affects you emotionally. It affects you creatively. It rewards you. It’s a kind of food that can’t be had in a grocery store. [laughs] It’s a kind of food that lets you know that you’re realizing your maximum potential and applying it in a worthy purpose. That doesn’t happen often enough, but it is sort of… It’s addictive.

Are there scenes that carry some importance to you?

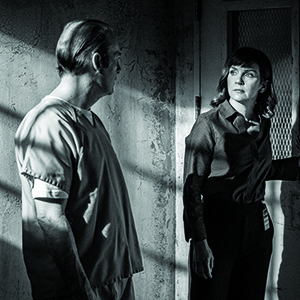

Yes. Several. One scene is when the De Niro character as the uncle, and the brother of the Leonardo’s character bring him to the Mason Hall and literally paddle him for his dissonance to their conspiracy. They punish him for not being on board completely for the murders and the consolidation of the mineral rights. We were in the real Mason Hall, one that carried the framed photo of the criminal Hale on its walls as stalwart member of the Local community. We were using real props and furnishings, and the environment was in the real place. This is the unveiling of De Niro the puppet master behind all of this. His facade to the community was as the benevolent intermediary between the Osage Nation and the white community, which was a cover for his true evil nature.

That was a very powerful scene to me, and it was also very challenging with huge wide framing, and a reverberant space. All the things that are sort of technical questions when you’re gearing up. I felt very, very happy about how we were able to take all of those challenging elements and somehow merge them into a coherent approach to the scene. We didn’t lose the space of the room, but we weren’t lost in the distance of the room, we were able to emphasize the accent points in the scene in terms of what the characters were doing by mic placement, by mixing, by levels, by all the different tools that seem like innocuous solely engineering things, but they’re actually paintbrushes. The way a camera can slightly move in on somebody for emphasis at a key moment, and to also do that with sound emphasizes that.

Another scene that really comes to mind that was hugely significant on an emotional level. This was the scene inside the ritual structure where the tribe was having their strategy session to send an emissary to Washington, DC to plead with the American government for some kind of relief for these continuing murders that were not being investigated, that were being ignored by local authorities, and state level. They met with the President of the United States. Consider the courage it took for the Indian Nation to go and create access, because their standing legally was as a separate nation. To be seen by the President of the United States, it was Calvin Coolidge, and to get a response. They’re one of the first cases of the FBI. That’s a central piece of the story in the original book.

During that scene, in between setups, one of the Nation’s present-day leaders who’s in the scene and is one of the principal characters, stood up and made a speech spontaneously to everyone present. We were not shooting, this wasn’t part of the film. He spoke about how significant this was and what it meant to them as a community, and the authenticity of Marty’s team to be stringent about respecting their story and the meaning of their story. Not only to themselves, but to the larger community of the country, and how much it meant to them. He was passionate and it was personal. As he started to speak, and I will be proud about this because I said, “Doug, get in there, aim that mic at the speaker, be delicate about it but do it.” I hit record and I got the whole thing. I felt great because I went to Marty at the end and I said, “Marty, we have that whole thing, it was recorded. Marty’s such a New Yorker, and he just lit up. He was like, “Fucking great. Oh my God.” He went back into the set and re-positioned the camera to zero in on this speaker to repeat for the camera as an honest improv, which is now in the movie. So that was another moment where we were moving from fiction to reality, because a lot of these people are descendants of those murdered people, and this was their story. It’s complex, and yes, the book was a New York Times bestseller but here this is all being distilled into a movie which is potentially a more significant cultural event in our present-day culture.

(Part 2 of this discussion will continue in the spring edition.)