by Steve Morantz CAS

In July of 2018, I was in New York City on vacation with my family when I got a text from one of my favorite producers, Jessica Elbaum, asking me if I was interested in doing a Netflix series with my most cherished actress, Christina Applegate. I already had another job lined up to start in September, and I would have usually said no, but with a two-and-a-half-month window and the opportunity to work with two of my favorite people at the same time, I couldn’t refuse. The show was Dead to Me.

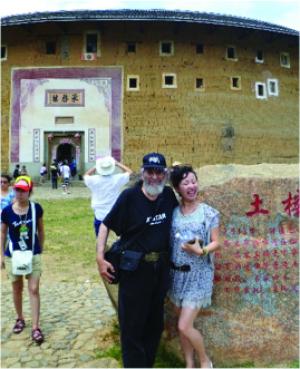

I first met Christina Applegate in 2007 when I worked on the pilot and two seasons of Samantha Who? To this day, I consider it my best all-around experience I have ever had on a job. If you ask the majority of the crew, they will tell you the same, it was something special. When the show was cancelled, I was extremely lucky to move across the CBS Radford lot to mix five amazing seasons of Parks and Recreation which turned out to be my second-best experience.

I kept in touch with Christina through the years, and we worked together again on the Up All Night pilot and later, the Los Angeles portion of the feature film Vacation.

I worked with Jessica Elbaum the first time on the feature The House. She came over to us and said, “I’m Jessica and I am good friends with Christina. She speaks the world about you and your team.” Since then, I have done four projects with Jessica.

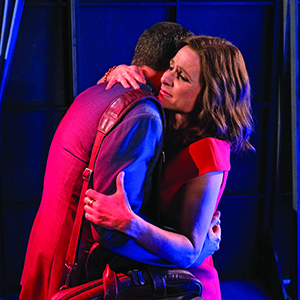

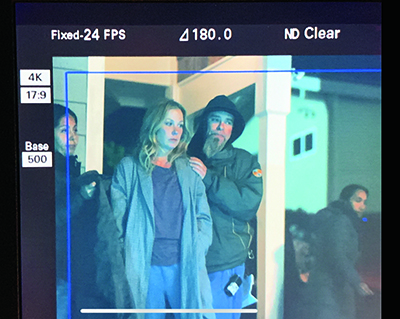

Dead to Me centers on ‘Jen’ (Christina Applegate), a recently widowed mother of two, whose husband was killed in a hit-and-run accident. In a grief counseling group, she meets a free spirit named ‘Judy’ (Linda Cardellini), who recently lost her fiancé. They bond and have many late-night phone calls helping each other cope through their difficult times. Judy is not who she seems, as her dead fiancé, ‘Steve’ (James Marsden), is actually very much alive, and eventually it is revealed that Judy and Steve were the ones who hit Jen’s husband with their car.

Judy moves into Jen’s guest house and between dealing with Jen’s two children who are having a hard time, the police investigating the hit-and-run, the Greek mafia, and Jen’s mother-in-law, things get crazy really quickly. There is a substantial amount of crying in Seasons 1 and 2. It has been labeled a dark comedy and it is definitely that. There is so much going on, enhanced by Liz Feldman’s fantastic writing and a great cast. Liz makes it all flow into one big roller coaster ride with each episode ending in a cliffhanger. It has become a big hit with Season 2 quickly greenlit. The reason for that success is that the majority of the writers and directors are women.

Both seasons have substantial practical locations The show is set in Laguna Beach, which they used for B roll. Instead, we spent a lot of time filming in San Pedro, the San Fernando Valley, and Raleigh Studios Hollywood in Season 1.

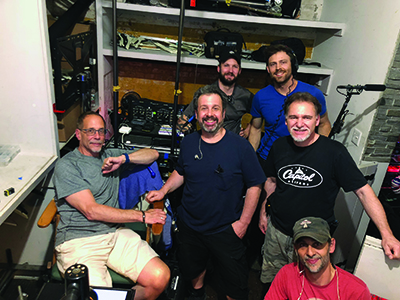

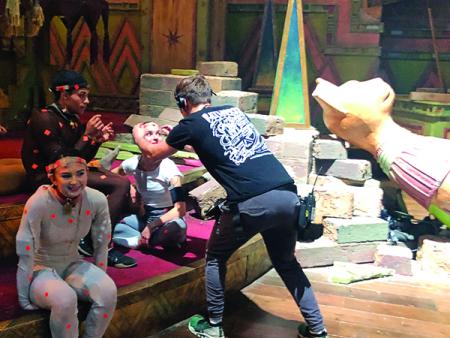

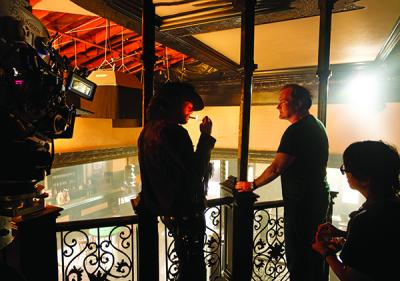

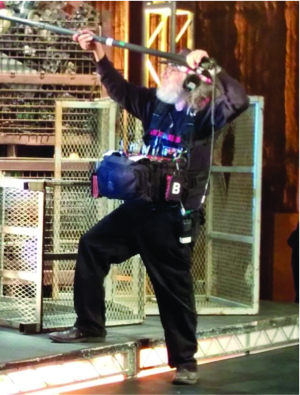

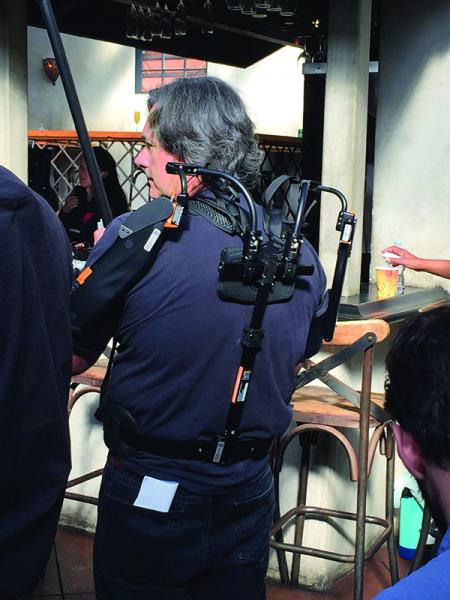

L-R: Steve Morantz, Dirk Stout & Mitch Cohn on the last day of Season 2

In Season 2, we shot in Glendale at Riverfront Stages, which had constant construction and a nearby equipment rental warehouse with condors running all the time.

The locations were not the most sound-friendly either, what locations are these days? We were always under the flight path when shooting in the Valley, close to the ocean in San Pedro, and a lot of locations by the freeways. The scripts called for a lot of soft-spoken dialog, when they weren’t crying or screaming, but we were able to always get what we needed.

My incredible team of Dirk Stout on Boom, working with me off and on for more than ten years, and Sound Utility Mitch Cohn, sixteen years and counting, always make my job easier than it should be.

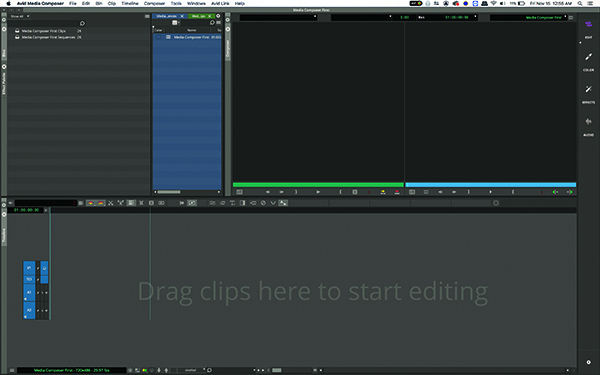

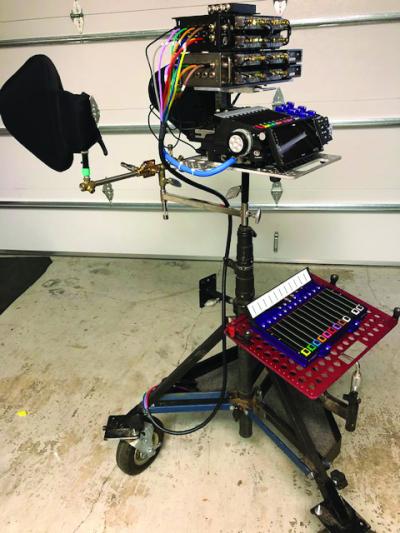

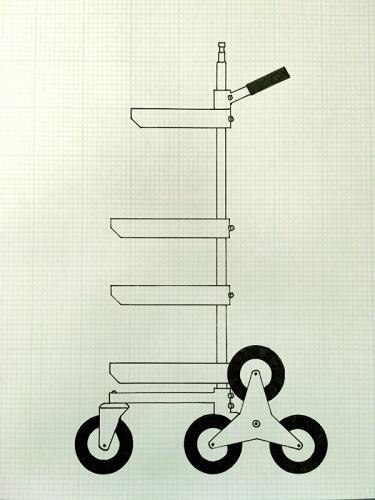

My cart consists of a Midas M32R Mixing Console, two Lectrosonics Venue 2’s and a Lectrosonics D2, a Sound Devices Pix260 and 970, Lectrosonics SMV’s, Comtek’s, and IFB’s. At the end of the season, I added a second D2 and one less Venue 2. My two Zaxcom 743 plug-on transmitters for the booms have been replaced by the Lectrosonics DPR.

My mobile setup is on a PSC Eurocart with a Sound Devices 688, Sound Devices SL-6, Sound Devices Cl-12, and Lectrosonics SRC’s. The 688 is in a bag, so whenever I need to go over the shoulder, I just disconnect two cables and I’m off and running.

For Season 1, my go-to lavs were the DPA 4061 and 4071 with the Sennheiser MKE-1 used in specialty situations, as well as the Sennheiser MKH-50’s and Schoeps Mini CMIT for the booms. In Season 2, we added the DPA 6060 and 6061’s into the mix.

On my first television series, I learned to always keep an open dialog with post production, and I check in every few weeks to make sure I am addressing all their needs with editorial and the post producers. If we are in a really bad location, I always drop them a line to give them a heads up as well. When I have time, I try to go to the mix sessions of every show I work on, which is a good way to get face-time with the re-recording mixers and to see if there is anything I can do to assist them in getting the best tracks possible.

Season 2 of Dead to Me premiered on May 8 on Netflix.