Mixing Live Singing Vocals on Cats Part 1

by Simon Hayes AMPS CAS

As I drove into Leavesden Studios in London, UK, to meet Tom Hooper to discuss his next project Cats, I knew that the film was going to be a huge challenge having seen the stage show. I hoped the conversation we were about to have would present possibilities to deliver a first-class soundtrack. I was aware that Tom wanted to record the vocals live but I’d also had conversations with various people involved in the project who thought it just wouldn’t be possible to go completely live due to the frenetic choreography and the difficulty our performers would have singing and dancing for the length of a film industry day.

The first question I asked Tom was, “Is it your intention to shoot the film with completely live sound?” He looked at me quizzically and with a wry smile he replied, “Of course, that’s why you’re here.” He moved swiftly into explaining his vision and how we were going to shoot the film, and the details of what he wanted to achieve visually and sonically. It was early on in the proceedings, and at this point the DP had not been chosen. As I listened intently, Tom told me about the VFX tests he had been doing which involved a new process that hadn’t been used before. We would shoot completely live action on the set, with actors who could sing and dance, and then in post, the actors would have fur added to them and become cats, whilst completely retaining their body movements and, most importantly, their facial expressions.

Tom and I spoke about the audience and how cinemagoers judge performance and the leap of faith they must have to trust what they are seeing and hearing on screen. Tom’s position in filmmaking has always been that audiences instinctively believe performances if the dialog is original and recorded on set. We spoke about how this is deeply rooted in human subconscious and is instinctively part of our fight or flight mechanism that has been one of the keys to our species survival. When we were hunter-gatherers, human beings had to assess every interaction by reading facial expressions and listening to the tone of voices; did a stranger want to steal from us, kill us, or collaborate in a helpful manner?

We do not switch off this subconscious assessment when we walk into a movie theatre to watch a film. We look at the actor’s facial expressions and listen to the tone of dialog and we instinctively wonder whether we trust what we are experiencing. Is the lip sync perfect? Does the dialog inflection match the facial expression? Is there an acoustic in the vocal that does not match the location of the actor we are watching on screen? All of these questions are being asked at a deep base level by every moviegoer. With this in mind, Tom continued to explain that the VFX process would be presenting audiences with something they had not seen before, human “cats.” Having the performers sing live throughout the film was one of the main strategies Tom had for helping the audience immerse themselves in the narrative.

As our conversation continued, I was getting more important information from Tom that would affect my pitch in how to capture the live singing. Tom explained that he wanted to showcase modern and exciting choreography that would involve break dancing, street dance, and parkour (free running, a dynamic, and explosive style based around gymnastic movements), as well as more classical styles like ballet. Up to this point, I had thought that due to the fur being painted onto the bodies in post, and the actors wearing mo-cap suits, it would be an ideal opportunity to place lavaliers on the body in vision, and that they would not have the usual clothing rustle. This workflow would not need to be signed off by the VFX team as they were adding a layer of fur anyway. Tom described the dancing tests he was excited about, and the type of rolling, tumbling, and break dancing the choreography would contain. I quickly realized I had to come up with a better strategy. Mics on the chest/solar plexus would be prone to getting impacted by the dance moves, and secondly, the excessive head movements of the style of choreography Tom favored, would mean the actors’ vocals would be going off axis regularly.

The first idea I pitched was using DPA ‘cheek’ mics on miniature booms that attach to the performers’ ears. Looking back now, I was extremely fortunate that Tom didn’t want to use this process, citing the fact that even though the VFX would paint fur onto the actors’ faces, the fur was going to be translucent so facial expressions could be retained underneath. Tom felt the cheek mics would need to be digitally removed before the fur could be added. He wasn’t concerned by the financial impact; Tom’s concern was potentially losing valuable facial expressions from around the mouth during the mic-removal process.

I had to think fast and come up with another idea. Fortuitously, my idea was actually going to provide our film with higher quality, richer vocals than the cheek mics. I asked whether I could attach a DPA lavalier to the forehead of each actor. I have always known this is a better position than the cheek for capturing high-quality vocals but I had never done an A/B comparison. This workflow was not my first pitch because it is notoriously difficult to stick lav’s to the forehead for a whole day without them losing adhesion, especially in a place where humans perspire, coupled with the fact the actors would be dancing all day in very high-energy routines. In my mind, this would result in re-sticks, lost takes, and actors with sore skin on their foreheads within a week.

Tom said, “Simon, there is so much expression in the forehead that I really don’t want to jeopardize.” I explained that this really was the only option if he wanted a guarantee under these very difficult conditions that I would deliver vocals that would not require any ADR.

Now we were negotiating. There are few things that make Tom Hooper happier than a negotiation, especially one that will creatively benefit his film. “How good will the quality of sound be if we put the mics on the forehead?” he asked. “Absolutely brilliant, Tom, it will be perfect and the greatest benefit will be that the singing will never go off mic, and most importantly for music vocals, the perspective won’t change when you cut from wide to mid to tight and back again.” This resonated with Tom, as we found this out while testing on Les Miserables.

Spoken dialog in films benefits from the perspective of the mic matching the camera angle, but with singing, any change in perspective, rather than helping the audience believe the performance, creates the opposite effect, drawing attention to the picture-editing process in an extremely uncomfortable, jolting manner.

This makes sense; when was the last time you heard any type of singing accompanied by music that has anything but a close perspective whether it be pop, rock, jazz, country, or blues?

Tom fixed me with a serious stare and asked, “If we put the mics on the forehead, will they sound as good as a close boom?” I replied, “Yes, I believe they will, because they will actually be closer than a boom could get and we will NEVER get caught unprepared by a sudden head turn. More importantly, I’m assuming we are going to cover this film with multiple cameras shooting wide, mid and tight at the same time to capture a perfect performance from all angles?”

“Yes, of course,” Tom replied, “and the sets are important to me. We are not shooting on green screens, and the cameras will often be handheld and frenetic so I’m not sure painting booms out is a viable option.” I responded, “I’m assuming from what you’ve described about the look of the film, your DP will probably use a lot of hard spotlights to achieve that.” Tom smiled, “Yes, that’s for sure. It seems we are certainly going to need to use the radio mics to achieve this; how can we make them work?”

Great, we were at a stage of the negotiation where I knew I had presented my case convincingly enough for Tom to help me find an answer to mic placement. “How about this compromise, Simon,” Tom said, “you keep the mics clear of the lower fifty percent of the forehead directly above the eyebrows where most of the facial expression inhabits, but you can have the upper fifty percent, below the hairline.” I answered, “We’ll get perfect vocals!” A big grin broke across Tom Hooper’s face; he reached out to shake my hand and said, “We’ve got a deal.”

Now, all I had to do was work out how to attach the mics and make sure the actors could perform and hear the music, keeping the vocals clean while collaborating with the Music Department. Most importantly, I had Tom Hooper’s support for my workflow; the first big hurdle had been crossed.

My next port of call was a meeting with my old friends, Supervising Sound & Music Editor John Warhurst and Music Supervisor Becky Bentham. John had worked on Les Miserables and was booked for Cats, along with Becky, who I have done many musicals, starting with Mamma Mia! more than ten years ago. They are both strong allies and we have a shorthand with each other. We completely trust one another and have a very strong relationship. The first part of our agenda was the team. We agreed that that there would be no demarcation between Sound and Music departments on Cats. This collaborative methodology had been extremely successful on Les Miserables and we agreed our team would be called Sound/Music. John and myself would head up that team on set every day with all the team members taking instruction from us, with support from Becky on the set and in an office at Leavesden Studios where we were shooting the entire movie.

Tom’s vision, along with Eve Stewart, his Production Designer, was that all the sets would be three times bigger than reality (doors, tables, chairs—everything!) because cats are about three times smaller than humans. We were fortunate that the entire film would be shot on soundstages with zero location work.

My next discussion with John and Becky was about Pro Tools operators. We had been very fortunate to work with a brilliant operator on Les Miz who has since retired and moved into another career. Becky has helped me find absolutely outstanding Pro Tools operators throughout my musical career and I really trust her judgment. She has her finger on the pulse of what is happening in the music industry and who are the best technicians, as she is based at Abbey Road Studios where she works closely with their staff and freelancers. Becky is also very aware of an important point: not every good music editor is the correct fit for Pro Tools work on films. Music editors in the music industry can work at a speed that is somewhat less pressurized than a film set. Every decision is based around music, whereas on a film set, the priorities are the camera and the visual image. To expand on that, a Pro Tools operator working on a film musical has to be extremely fast, quick thinking, and realize that no one is going to wait. With this in mind, we discussed her recommendations and I quizzed her on their personalities, technical expertise and whether they would be able to work in a highly pressurized environment for more than three months, twelve hours per day. We kept coming back ’round to the same name—Victor Chaga.

I met Victor the next day. He is a Russian who moved to LA as a young composer looking for his big break. He instantly struck me as being made of the right stuff as he had the emotionless confidence I associate with many Russians, coupled with the desire to provide excellent service I associate with American culture. When I interview music editors for a position on my team, I always ask how they would react to a number of precise extreme scenarios on set. I was confident we had found our guy!

The hiring of a first-class music editor/Pro Tools operator was incredibly important on Cats, because the whole film is driven by tempo—unlike Les Miserables, where tempo could be manipulated and sometimes ignored in favor of performance. The rhythmic dance routines of Cats meant that we needed to be able to drift in and out of pre-recorded playback tracks and live piano constantly. Tom still wanted to use the live keyboard whenever possible to allow the actors the opportunity to play with timing and let their emotional performance take priority. This was mainly between the songs or in small breaks in the tempo. Victor would be playing his Pro Tools rig as if it was a musical instrument, accompanying its own highly creative ‘dance’ with the live keyboard player, so the two instruments could immerse the actors and support them in their performance.

Everyone involved in Cats, from Tom Hooper and Producers Debra Hayward and Ben Howarth, and Executive Producers Eric Fellner and Tim Bevan from Working Title, to Andy Blankenbuehler our Choreographer, kept expressing how dynamic the choreography was, and how loud the music needed to be for the actors to dance to. I needed to find a way to get more volume to the actors than would be possible using the ‘earwigs’ and induction loops we had used on Les Miserables.

It became obvious to me that for the extreme SPL’s that some of our performers would require, we needed to use personal ‘in-ear’ monitors that would be custom-molded to the performer’s ear canals. I already had a great relationship with Puretone who supply all of my musicals with custom- molded earwigs and also supply many rock performers and musicians with custom personal in-ear monitors to use on stage. They’d actually just supplied the same product on my last film, Danny Boyle’s Yesterday for the star, Himesh Patel.

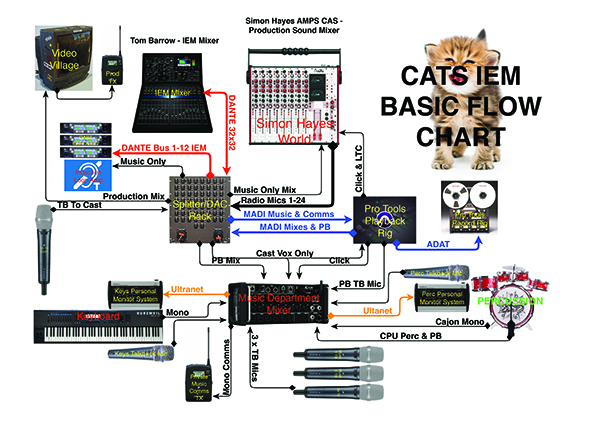

I decided that Cats needed a completely new strategy for IEM’s and that my production sound mix for Tom Hooper and his editor, Melanie Oliver, would not always be suitable for the performers to listen to as we were shooting. I really wanted them to feel supported. I also knew that many of the cast came from a music industry background and would expect a personal mix in their IEM’s, something a front-of-house mixer would usually provide for them on stage. I have been working with my 2nd Unit Sound Mixer, Tom Barrow, on a number of films now. Tom’s former career was working in a music recording studio as an engineer, so it seemed to make complete sense that he should join our team as the Cats IEM mixer.

I explained to production that hiring Tom Barrow would be an additional expense that they were not anticipating, but that Tom Hooper’s expectation would be difficult to achieve without having a huge Outside Broadcast (OB) truck parked at each stage if they didn’t take my advice. I explained to Working Title that if they wanted me to stay ‘small’ enough to not require the expense of OB trucks. they had to accept that Cats was completely unique and would require a large Sound/Music team, potentially larger than any previous film ever shot. Luckily, my relationship with Eric Fellner and Tim Bevan at Working Title and their Head of Production, Sarah-Jane Wright, goes back fifteen years over multiple films. They told me they trusted me and would facilitate whatever I needed to support Tom Hooper’s vision. Of course, they did let me know they were not expecting any ADR, so the pressure was on! Their Unit Production Managers, Jo Burn and Nick Fulton, were also incredibly supportive throughout.

I decided to hand the IEM workflow and process over to Tom Barrow as I prioritized the vocal recordings and the rest of the music workflow.

We were actually creating a world for our performers to inhabit that would sonically block them off from outside voices and sounds with their IEM’s. Our cast was given the choice of wearing a single IEM or a pair. Many of our cast come from a music industry background so most preferred to use a pair. This meant that the IEM mixer had to become a conduit for all the information and effectively provide a comms mix, alongside the dedicated mixes for the performers in order for them to communicate with each other, or for the director, 1st AD, keyboard player, music producers, and Pro Tools op to communicate with the cast.

At this point, it was fourteen weeks out from principal photography and it was becoming clear that I was spending many hours of the day working on telephone calls or meetings. I needed to start splitting the workload if we were to achieve this monumental task and be ready to shoot. To provide support and creative input, I needed my longtime key 1st assistant sound (UK term for boom operator) to start work. Arthur Fenn has worked on every single one of my fifty-eight movies. We have a collaborative approach and I consider Arthur to be one of the best boom op’s in the world. The industry has changed over the last fifteen years with large, multi-camera VFX movies becoming the norm. Arthur has, in turn, become a radio mic expert. His skill is collaborating with the actors. He has an engaging personality, an easy rapport, and a fearlessness that quickly means he is considered in much the same way a personal costumier would be with the cast. He also collaborates very closely with the Costume Department from the beginning and creates a strong working relationship with that team. I approached production and explained that it was time for both myself and Arthur to be hired full time, fourteen weeks out. That would be the requirement if they wanted us to be ready on time. They agreed and I sat down and brainstormed with Arthur regarding how we could attach the mics to the cast’s foreheads.

Arthur strongly advised against trying to stick the mics on their foreheads for the reasons mentioned previously. When told about the IEM’s the cast would be using, he expressed his concern about the practicalities of so many cables being unattached and pulling on the mics and IEM’s during explosive choreography, so we came up with a plan. It was born out of the knowledge that some puppeteers have used tennis players’ ‘sweat bands,’ so we started discussing that strategy and that led to ‘lav straps’ which are a relatively new product that actors wear around their chests. Arthur said, “What we need is a lav strap for the head which keeps the cables tidy, can be washed overnight if necessary, and can also double as a sweat band which could be helpful to the performers.” This is where our strong relationship with Simon Bysshe of URSA straps came in. We have known Simon since he was a young trainee who did a film with us, and when his company URSA was in its embryonic stages during Guardians of the Galaxy, Arthur and myself did a lot of work with him on product development. We also tested his prototype straps on set. I sent Arthur off to meet Simon and together, they came up with a design for the bespoke Cats mic and IEM head strap system.

Arthur and I went to watch a choreography rehearsal to get a feel for the movements and to start to consider where we would rig the mic transmitter and IEM receiver packs. The choreography team had continually expressed concern to production that the performers may get injured if they landed on a pack. Tom Hooper had called me into a meeting to ask that we use the very smallest packs available.

We arrived at the rehearsal with a bunch of different generic URSA straps (thigh, ankle, waist, etc.) and two wireless packs. We had a couple of hours with one of the dance performers who tried different positions on his body, and then showed us lots of different dance movements from ballet, tap, street, gymnastics, and break dancing to represent the diversity of our cast’s routines. The choreography team tried to assess which positions were best. It quickly became clear that there wasn’t “a best position,” and that our workflow for each performer throughout the film would depend on the unique movement they would be doing in the scene or shot. This meant that every performer would need to let us know how they would like to be rigged each day, and sometimes on a shot-to-shot basis, to avoid the packs restricting their movement or causing the risk of injury. We had the usual options of ankle, thigh, and waist but we also developed a shoulder/chest strap with URSA that was used for a large percentage of the film. This kind of ‘holster’ strap, with choices of where the packs were placed—whether that be pec, armpit, or shoulder area—very rarely made contact with the ground. At the end of this test, Tom Hooper arrived and asked the performer, “Can you dance unrestricted wearing these packs?” His reply was “Yes,” and Tom turned to Arthur and myself and said, “Great work, let’s keep moving forward. We have some news from VFX that I need to discuss, so let’s meet tomorrow.”

The next morning, Arthur and myself attended a VFX meeting set up by Tom Hooper’s producer, Debra Hayward, and Producer/1st AD Ben Howarth, Executive Producer Jo Burn, and UPM Nick Fulton. Tom Hooper’s Costume Designer, Paco Delgado, and members of his team were present as well.

The VFX team explained that they would be recording each performer’s body movements using a box the size of a small hard drive attached to the performer’s body, linked to tracking markers (tiny buttons) in key points on the body. The big question production wanted answered was, “How big is this box, and who is going to rig the performers?”

The VFX Department explained that they needed the hard drive capture boxes attached because it would not be technically possible to capture that many different performances by radio link as that technology simply didn’t exist. The movements of each performer would be recorded on the hard drives, which would all be jammed to timecode, and at the end of each day, the information from each hard drive would be downloaded.

The VFX team needed help to implement rigging the actors. Generally, VFX teams don’t rig and de-rig actors. The whole process was becoming extremely unique as there would be elements of costume on some cast, but many of the chorus would simply wear a motion-capture suit. Rigging them with sound and vfx equipment would be the most time-consuming task. Another factor that had become clear in the last few days was the number of cast: about fifty in EVERY shot!

I suggested that we needed to forget about standard film industry workflow and protocol, and treat the film as a unique entity. I explained that it would not be possible for fifty performers to go through Costume, then Sound, then VFX before coming to set every morning. Tom Hooper wouldn’t get his cast until lunchtime! I said that it would be counterproductive having the Costume Department dressing the cast in mo-cap suits, then having the cast undress to have sound equipment strapped to them. I suggested that my sound team could rig the actors with the vfx and sound equipment, with VFX present during the process to technically assist and troubleshoot their equipment.

We started talking about the amount of time to do the rigging, and the number of people that we would require. It became clear that we needed to throw a large team at the issue to enable the fifty cast to be on the set within an hour of arrival at the studio. After much discussion, we decided that Arthur Fenn, 1st AS, would head up a team of sound “suit techs,” which became our team on Cats.

Five 3rd assistant sound people would work each morning and evening rigging and de-rigging the cast under Arthur’s instruction, each with a costume dresser and a VFX technician as a three-person team. They would dress a single cast member, then move onto the next. We would try wherever possible to keep the same three-person team working with the same actors each day so they could develop a relationship with the actor to help them feel comfortable and supported. When the cast were dressed, the five suit techs would come to the set and join the rest of the Sound Department. They would stand by to troubleshoot ‘their cast,’ moving packs around depending on the dance routine or movement. They were on call to make sure their actors were comfortable, in the same way a personal costume dresser would be on a ‘normal’ film set.

I cannot stress enough how much time/management coordination went into this process with Arthur and his team of suit techs, using Excel spreadsheets to work out the daily timings and strategy based on the next day’s advanced call sheet. It really was a tour de force in organization. The other really helpful factor was that our suit techs had experience working on ‘normal’ films and had radio mic’d actors before, so they were arriving on Cats with a skill set already in place.

Arthur also coordinated with the VFX team and URSA’s Simon Bysshe. Simon was working full time on making unique URSA STRAP solutions for Cats, that included custom-sized straps to attach the VFX hard drive packs to the bodies of the performers. Everything was coming together but we still had a lot of preparation to do.

I sat down with John Warhurst, Supervising Sound/Music Editor, Melanie Oliver, Picture Editor, and her 1st Assistant, Alex Anstey, and discussed the fifty cast members. Tom Hooper and Working Title did not want to go down the route of using an OB truck outside the stages, as Tom wanted to be able to move fast from stage to stage. I was also concerned that if I was based off the set in a truck, I would be creatively divorced from proceedings on the set. I feel that the closer I can be in proximity to the director, the more supportive I can be and positively influence the recording of the performance on the set. I can’t stress this point enough.

We continued by talking about how many tracks the Avid could ingest, and how many tracks I felt I could actually mix on the set successfully. I invited my other 1st Assistant Sound, Robin Johnson, into the conversation. Robin has another diverse skill set that complements Arthur and me, and is a reason he has been with us on our journey since 1998, joining us on our second movie. Robin is our technical genius, qualified as a scientist and an absolutely first-class audio engineer, computer expert (Mac & PC) and, of course, boom operator. I asked Robin to come up with some frequency plans to try and determine how many radio frequencies we could get reliably working together on one stage, bearing in mind the additional frequencies that would be necessary for IEM’s and comm’s, as well as the radio mics.

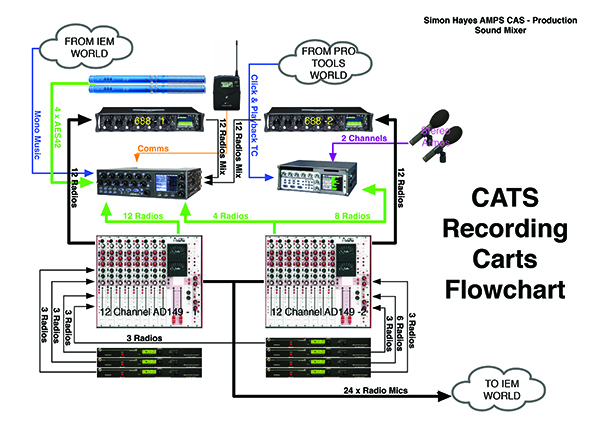

When we started looking at our planned workflow, we needed a little more than fifty frequencies to work in close proximity on one stage. The most radio mics we could assign to actor vocals was twenty-four. After breaking down the script in conversations with Tom Hooper and the music team, we knew that eighteen soloists would need mic’ing every day as they were key cast members that would sing solos. The rest of the cast would sing the chorus. When I spoke to Tom Hooper about my plan to only mic twenty-four of the cast, he was unconcerned. He explained that the chorus had been cast primarily for their extraordinary and diverse dancing ability. Tom did not feel we needed all of them mic’d because of the time it would take to get fifty performers wired, as well as the fact that many of them were not singers but dancers.

We worked out a plan. Eighteen soloists would always be mic’d and the other six radio mics would be assigned on a day-by-day basis to the strongest singers in the chorus. This was based on which song we were shooting and how to support the soloists on those tracks with the exact mix of baritones, altos, tenors, etc. The decision on whom to mic was made by the Vocal Coach, Fiona McDougal, and our two Keyboard Players, James Taylor and Mark Aspinall. They were very adept at working out exactly where to place the six ‘floating’ radio mics on a scene-to-scene basis, as they knew the cast’s voices, their strengths, weaknesses, and how they could be played to enhance the backing vocals. Phew—we only had to run twenty-four radio mics EVERY scene, EVERY day!

Our next step was how to deliver those twenty-four tracks to Editorial daily.

I had been waiting for the Zaxcom Deva 24 to arrive specifically for Cats. Glenn Sanders and Roger Patel at Everything Audio, the UK Zaxcom distributor, managed to get me a very early machine to use on the additional photography we were doing on Aladdin, right before we filmed Cats. Being able to use the Deva 24 for a few weeks before bringing it onto Cats was very important to me. I found it very similar to my Deva 16 in the usual Zaxcom style. I am a firm believer in making Production Sound Mixing as intuitive as possible. I believe the equipment is only there to help and support the creative process of the director and sound mixer. The equipment I am using is no different than the instrument a musician plays. It would be unthinkable for any musician to play a new instrument before the most creatively complex and demanding concert of their career. I decided that track count would not decide which recorder and mixer panel I would use. I was going to have to use a second recorder because of the high track count; this was going to be the highest track count I had recorded and mixed in my career, with an extremely diverse group of vocalists, all with different styles and levels.

I wanted to give myself the best chance of capturing every subtlety and nuance of the performances, with the most appropriate gain structure. In order to give myself the best chance of delivering this, I decided to stick to equipment I had been using for years, but make it more expansive. I was already using a custom-built twelve-channel Audio Developments AD149 desk. Their previous largest was ten channels. The company MD Tom Cryan had made my twelve-channel specifically for me. Of course, like all reliable production sound mixers, I had a spare built at the same time, just in case I was in some far-flung location and had a failure. It soon became apparent to me, however, that if I linked the two mixers together to deliver twenty-four tracks, I would not have a spare if there were a failure. My mixers were unique and we would be completely reliant on them for Cats. I made the decision to task Audio Developments to build another two from scratch, so I had complete peace of mind that if the unthinkable happened on set and both mixers died or developed faults, I could swap them out and the shoot could continue.

The next decision was recorders. I decided, with Editorial’s permission, to link together the Zaxcom Deva 24 with my Zaxcom Deva 16. This would give me access to forty tracks. I would then create two mixes for Picture Editorial, allowing them to expand on choruses if they wanted to by using both mixes in the Avid. Mix Track 1 contained a mix of the first twelve ISO tracks, and Mix Track 2 contained a mix of ISO tracks thirteen through twenty-four. We assigned the first twelve ISO tracks to our key cast members who would be in every scene. When we had a guest star in the cast for a specific song or two, we would decide the most appropriate workflow. I would also try to keep the actors with the highest amount of solo singing on the first twelve ISO tracks and Mix 1, with Mix 2 being a ‘supporting’ mix, which could be added or subtracted by Melanie Oliver, the Picture Editor.

This suited Melanie because it gave her creative control over the ‘size’ of the sound in the Avid, without giving her and her team the additional workload of having to dig into the ISO tracks to rebuild the mix. Of course, all the ISO tracks were ingested into the Avid so Picture Editorial had access to them, but the plan was for Editorial to only work off the two mixes whenever possible.

We then took the conversation into the musical side of the production sound recording. We had two elements as discussed earlier: The electronic keyboard would be used wherever possible in links between songs to give the actors more freedom to explore tempo, so they could play with their performances.

Pro Tools playback of temp mixes digitally orchestrated.

The keyboard and Pro Tools would need to weave in and out of each other so the actors did not hear a shift in tone between the two accompaniments in their IEM’s. This would be achieved by careful gain matching. We also learned early on in rehearsals that the best strategy to achieve this perfect blend was to have the keyboard player play along with the Pro Tools playback. It worked because when we went from free form keyboard to playback, it was not obvious to the cast, because they could still hear the keyboard.

The keyboard players, James and Mark, were actually ‘performers’ in Cats, just a different kind. They were not on screen, instead spending twelve hours a day in a soundproofed booth we had built, with large LCD screens to view all the camera angles, such was their creative input on the set. The irony being that both the expressive keyboard playing and the Pro Tools playback were simply temporary. It would all be discarded when Cats was fully orchestrated in post production, but what remained was the emotion they helped the cast achieve.

I decided adding the musical element to the two vocal mix tracks would be counterproductive. Melanie would need two tracks of vocal mixes that would give her control over the size of the sound, and a mono keyboard/Pro Tools track.

At this point, there were two vocal mix tracks, twenty-four vocal ISO tracks, and the mono music on track twenty-seven. Melanie would have the ability of manipulating the volume of the keyboard/Pro Tools playback against the vocal mixes, as per her own and Tom Hooper’s instinct, on the Avid. She would also have the stereo ‘bounce backs’ of the temp Pro Tools orchestrated tracks, timecode locked so she could utilize this as she finished cutting a scene.

The ‘mono mix’ of keyboard and pre-recorded temp track was on Victor Chaga’s Pro Tools cart and it was his responsibility to keep it gain matched and send it direct to my Deva 16. Victor also sent it to Tom Barrow the IEM mixer at the same time so he could use it to create his individual IEM mixes for the cast, along with the vocals.

I sent Tom all of my ISO tracks as well, so he could creatively provide each actor with what they wanted and work each character’s gain in the IEM mixes. This gave Tom far more ability to support the cast than if he had simply been working with my production sound vocal mixes. It was invaluable to have Tom Barrow giving the cast what they needed to hear on a shot-by-shot basis so I could concentrate on what Post Production needed, and ultimately provide the highest quality vocals for the finished film.

Now onto timecode.

We were using an Ambient Master Clock on the sound cart, generating time of day TC that locked together sound recording, digital cameras, and VFX. Each Pro Tools temp song had its own unique timecode, so Picture Editorial could quickly drop the on-set music ISO and sync up the stereo temp version of the song in the Avid quickly and efficiently. The playback timecode fed directly from Pro Tools was recorded on audio track twenty-eight of my Deva 16. The Pro Tools playback timecode was also fed to the Lighting Desk so that lighting cues and moves could be triggered, ensuring that the complex lighting signature of each beat in the song would be frame accurate on every take we filmed.

We were now twelve weeks out from principal photography and I decided that the workload was growing too quickly for Arthur and myself to deal with on our own. After another meeting with production, I made a case for more of our Sound Department to start work full time at Leavesden Studios. Working Title and Tom Hooper were receptive to the idea after I explained the technical complexity of what we were all embarking on. This was the point where the performers were moving from their rehearsal studios to begin rehearsing on the actual sets we would be shooting on. This was very important for the choreography because the sets were three times larger than reality. My main point was that making the performers feel comfortable and supported by the process was absolutely paramount to them being able to give their best performances when we were shooting.

Up until this point, they had been rehearsing with keyboard and playback coming out of a small PA system operated by the vhoreography team, and vocals had not been a priority. Our cast was a mixture of film actors, theatre actors, musical theatre performers, ballerinas, and rock/pop/R&B vocalists. I felt it was incredibly important to introduce them to the workflow of singing and dancing with the TX/RX packs and hearing themselves in their IEM’s, to help them achieve the perfect balance of vocal and music for their own particular needs. We did not give everyone a completely unique custom mix, as this would have meant twenty-four separate IEM mixes. Instead, we tried to group performers together, based on their taste and the range in which they sing. Some of our main cast were able to have a completely personal mix, especially if that was what they were used to from performing on stage, but most cast were given a choice of a set few mixes.

We also decided that giving all fifty cast personal IEM molds with receivers was cost-prohibitive, so chorus members twenty-five through fifty were fitted with personal molded ‘earwigs’ being fed audio from an induction loop. This was the way we did Les Miserables, so we knew it worked well although at a lower SPL than the IEM’s. We didn’t put vocals into the loop, only the music playback, to help us get more volume for the beat of the music out of the earwigs. This section of the chorus was not being radio mic’d and were primarily incredible dancers rather than vocalists. We felt it would not hamper their performance in any way and they generally worked with only one earwig so they could hear the music to keep them in time; their other ear was open so they could hear the live singing on the set.

In rehearsals, this whole process had been auditioned and fine-tuned. As I said to the producers, if we do not spend twelve weeks rehearsing the workflow, we would waste time on a very tight schedule due to cast availability when we started shooting. I explained that if a performer has a sound problem, it could easily suck up a half-hour working out exactly what blend they want in their IEM. It would be terrible if that happened with a whole crew standing by, waiting to shoot on a very exacting daily schedule.

On our first couple of rehearsal days, that was exactly what happened. The producers present were shocked at how much time it took sorting out the performer’s IEM mixes, instead of rehearsing the choreography. They realized just how important their decision was bringing the Sound/Music team in twelve weeks out.

I also expressed that creatively I really needed to get a feel for the way the songs were being performed, and the dynamic range each vocalist used. I think because our visual colleagues don’t “see” sound, it is often assumed that dialog/vocals are just simply captured by a mic and that there is no need for a gain structure.

One of my biggest responsibilities and the core of my job were ensuring the vocals were captured as richly and perfectly as possible and that meant understanding the volumes our vocalists would use. I started to get familiar with which performers had huge dynamic range and which were the softer singers. I started taking notes and feeding that information to Arthur on where I wanted the gain settings to be on the Lectrosonics SMb transmitter packs.

I am a great believer in recording full dynamic range and I don’t like hitting the internal limiters in TX packs, even on loud pieces. The limiters in the transmitters cannot be completely turned off so I like to set them so that on a vocalist’s loudest part, the limiter is not engaged. Each performer was given their own unique gain setting on their TX, which would change from song to song dependent on the kind of performance they were giving. When I first heard Jennifer Hudson and Taylor Swift sing, I was shocked at their dynamic range and the way they used their voices. In order to capture their vocals in the purest way possible, I had to ask them to wear two radio packs with two DPA 4061 Core mics. The mics were rigged next to each other in their headbands but the TX packs were given two different gain settings that varied by about 6db. This gave me the best chance of capturing the lowest level pieces of their performances with perfect signal to noise, and the very highest SPL parts of their performances without hitting the TX limiters. Taylor and Jennifer were both assigned two tracks on the Deva with notes made for the Music Department regarding the track designation. Taylor and Jennifer were very supportive of this workflow and understood exactly why we were doing it this way after Arthur and myself explained the process to them. Tom Hooper asked, “Why are they wearing two mics?” and when I explained it to him he exclaimed, “That’s genius!” That is how excited Tom gets about capturing live performances. He is incredibly enthused by the process.

Another thing that came about in the rehearsal period was that our Keyboard Players, James and Mark, asked for a click track into their ears. Even though they were allowing the performers to have the freedom to express themselves when they were not locked to a playback track, they wanted to have a tempo guide for the next song when we moved into playback. John Warhurst, Supervising Sound/Music Editor, told me it would be incredibly helpful for him while he was editing to have access to that click. It was generated on Pro Tools and fed directly to my Deva ISO track twenty-nine. Phew! We were up to twenty-nine tracks of my forty tracks available.

The opportunity to use booms to capture the performances would be rare, due to the hard lighting style DP Chris Ross was using, alongside the huge sets and multiple cameras. However, we needed to be ready for any opportunities that would arise. We decided to use Schoeps Super CMITS, which are a very good match for the DPA lavs. The Super CMITS provide us with two AES 42 tracks from each mic, processed and unprocessed, so Nina the Dialog Editor could choose which track was more effective in post for any vocals where we used the booms.

There were no inputs for the boom mics on the AD149 mixers; they were already full with the twenty-four radio mics. However, the Zaxcom Deva 24 could take their signal on its AES 42 inputs. I would rarely use the booms in the mix so it made sense to keep them completely in the digital domain, which was a huge step forward in sound quality. This resulted in another four tracks assigned to the Deva 24, our total track count was now up to thirty-three.

In the end, we rarely used the booms apart from capturing the clapperboards. The radio mics sounded great, and the spotlights didn’t allow booms to get close, so we prioritized the mics that sounded best for the project and they were the head worn DPA’s. There are a few sporadic boomed pieces of dialog in the film and a few spot FX, but ninety-five percent of Cats was recorded on the DPA lavaliers.

One question that kept coming up since my first meeting with Tom Hooper, and in multiple meetings with the producers and Working Title Films, was how was I going to deal with the footfall from such dynamic choreography? This had not been resolved when we started rehearsing. I recorded a camera test and used that to start negotiating with the performers and with Tom. Up until this point, the cast had been rehearsing in whatever shoes they felt comfortable dancing in, knowing that their feet would generally become cats’ paws in VFX. After the test shoot, I played Tom the recording and told him we needed to rethink this protocol.

Tom was adamant that he did not want to do anything that limited his cast’s ability to dance in the most extreme way their skills allowed. Many of the cast were professional dancers. Tom was concerned that if someone got injured due to wearing inappropriate footwear, it jeopardized shooting and could damage the performers’ future career.

We had a frank and honest conversation as I explained my issue. Also present was the brilliant Paco Delgado, the Costume Designer. If any performer opted for heavier footwear than they actually needed, it would be contributing to making the live vocals poorer. It would be counterproductive to go through the fantastically difficult, energy-sapping process of recording the vocals live, only to find out footsteps had ruined the recordings and having to go into ADR to fix it.

High heel shoes treated to remove footfalls with safety for the dance

It was decided that each performer would have three levels of footwear and they would choose whatever they needed that was appropriate for a particular scene or dance move. I was very lucky that many of the cast had classical ballet training even if they were now street-style dancers, and were generally happy to perform in bare feet or ballet shoes unless a particular move or song demanded more support on their feet.

The three choices for the performers were bare feet, ballet shoes, or a type of shoe Paco and his team found that was halfway between a ballet shoe and a trainer and were designed for parkour (free running). The footwear was always near the set and available at all times. If Arthur saw a performer wearing heavier footwear than he thought a particular piece of choreography required, we would ask them if they could change shoes or go bare foot. Most of the time, they would realize they had forgotten that they were wearing parkour shoes and change them immediately.

This was a very productive process and it removed approximately seventy percent of the heavier footfalls from the live-recorded vocals than we would have otherwise encountered. There were a couple of dancers whose moves were so extreme, they had to wear trainers, and sometimes a character would be in high heels for a song; we took care of this the same way we would any other film, and treated the soles as much as we could while still keeping them safe for the performer.

Our soundproofed keyboard booths were first developed on Les Miserables. We needed to put a keyboard into a ply box that was on castor wheels and soundproofed, so we would not hear the noise of the electric keyboard being played on set. It worked successfully, but on Cats we wanted to go bigger and better. One of the discussions with production was about the complexity of our Sound/Music technical workflow and how quickly the equipment could be moved from stage to stage. Right now it was two production sound carts, two IEM mixing carts, one Pro Tools cart, and a keyboard booth, all linked together by a myriad of cables in the analog, digital, Dante, and MADI domains.

Unfortunately, because of artist availability and time constraints, there were many days in the schedule where we had to move stages. We were asked to look at where we could save time within our workflow, and one of the ways was to have construction build three keyboard booths, all containing a keyboard, flat-screen monitors, Midas mixers and the cables pre-rigged. The booths would be leap-frogged to the next stage by a swing gang on a telehandler or forklift truck to enable us to move from stage to stage and have a fully rigged booth waiting for us.

Our stage moves would still take us three hours for Sound/Music to be able to be ready to shoot. These moves were generally timed to coincide with our one-hour lunch break, which we would work through, and then by the time that stage was lit and cameras were ready, we were all in the same ballpark. The important factor was there was no way for the performers to rehearse until we were ready. They could block a dance routine with the choreographers counting out a rhythm verbally, but until the keyboard, Pro Tools, IEM’s, and radio mics were rigged, our cast could not hear any music, or each other, so the whole show was extremely reliant on our team being ready.

The three booths we had built for Cats were made of double-skinned ply with an eight-inch cavity in the walls, ceiling, and floor. We had construction spray expanding foam inside the cavity. The interiors and exteriors of the booths were lined with rubber-backed carpets. This meant they were completely soundproofed from interior noise escaping, and they were also soundproofed from exterior noise penetrating the interior. Our Keyboard Players, James Taylor and Mark Aspinall, had complete privacy.

I have already mentioned that James and Mark were actually performers on Cats, such was their creative collaboration and support they gave the cast. Not only were they playing the keyboards, they could also give verbal counts for anyone who needed them, directly into the cast IEM feeds. On many songs, Fiona McDougal, the cast Vocal Coach, was also inside the keyboard booth using a Shure SM58 mic, harmonizing or singing along to support the cast in their IEM’s during a scene. Fiona also did this when rehearsing with them for weeks in prep. It was an amazing sight to behold.

It was important to have two keyboard players, as we needed one to be present while filming a scene and the other rehearsing with a performer on a different stage due to artist availability and a very compressed shooting schedule. They would rehearse with Fiona, a keyboard player, and one of the choreography team. It was a very finely tuned machine and a tour de force of planning and scheduling.

John Warhurst and Victor Chaga devised the fantastic idea of using a foot pedal to trigger Pro Tools playback. This meant the keyboard players were ‘playing’ Pro Tools just like another musical instrument! Whichever keyboard player rehearsed, a song with a key performer would be the same person who played keyboard on that number when we shot it. This was extremely important as they had built up a rapport and understanding with that actor. We wanted to give the performers as much creative support as possible during their physically demanding experience of dancing and singing live. Victor made sure the playback cues were lined up so the keyboard player could trigger multiple cues and weave in and out of Pro Tools playback and live keyboard playing multiple times within a take. This was an extremely creative collaboration between the Sound/Music team and the cast.

Each one of us became part of a band ‘playing’ our own ‘instrument’ that would become an organic and intrinsic part of the piece. It was an incredible collaboration of which I am so proud to have been a part.

The Cats Sound Crew

Simon Hayes, Production Sound Mixer

John Warhurst, Supervising Music and Sound Editor

Becky Bentham, Music Supervisor

David Wilson, Music Producer

Arthur Fenn, Key 1st Assistant Sound

Robin Johnson, 1st Assistant Sound & Sound Maintenance Engineer

Tom Barrow, I.E.M. Mixer

Victor Chaga, Pro Tools Music Editor

Mark Aspinall, Music Associate/Keyboard Player

James A. Taylor, Music Associate/Keyboard Player

Fiona McDougal, Vocal Coach

Ben Jeffes, 2nd Assistant Sound

Taz Fairbanks, 3rd Assistant Sound

Oscar Ginn, 3rd Assistant Sound

Francesca Renda, 3rd Assistant Sound

Ashley Sinani, 3rd Assistant Sound

Kirsty Wright, 3rd Assistant Sound

Editor’s note: “Mixing Live Singing Vocals on Cats Part 2”

continues in the winter edition of Production Sound & Video.