by Amanda Beggs CAS

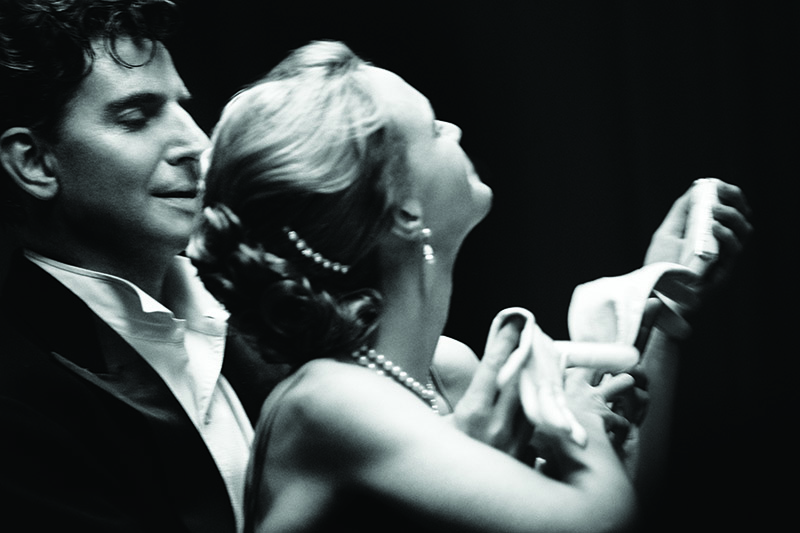

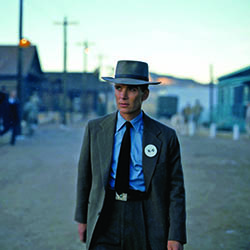

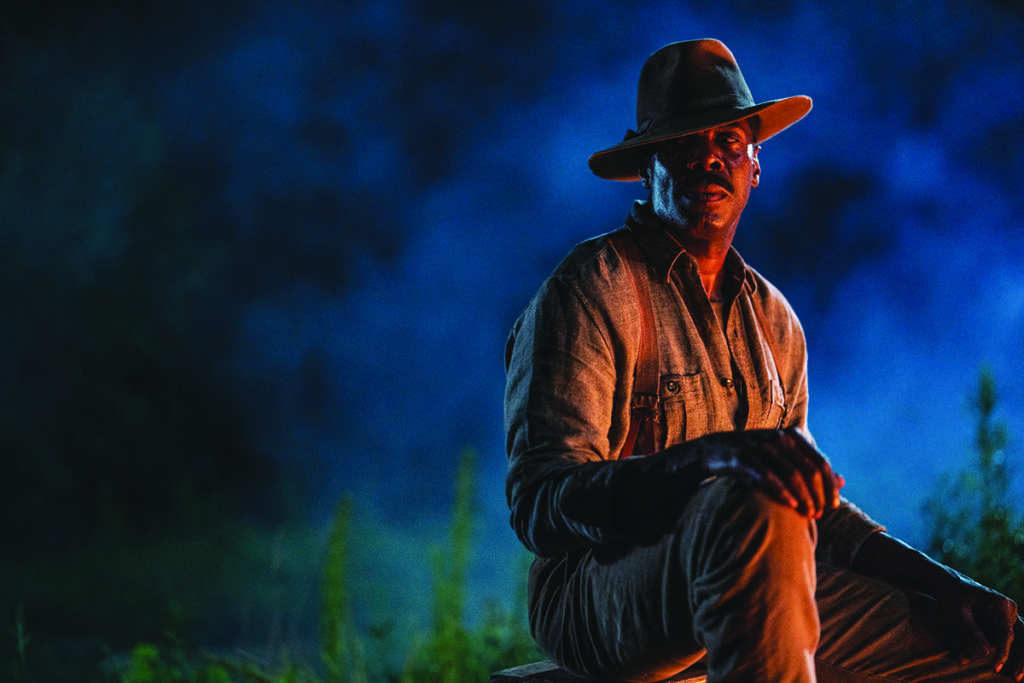

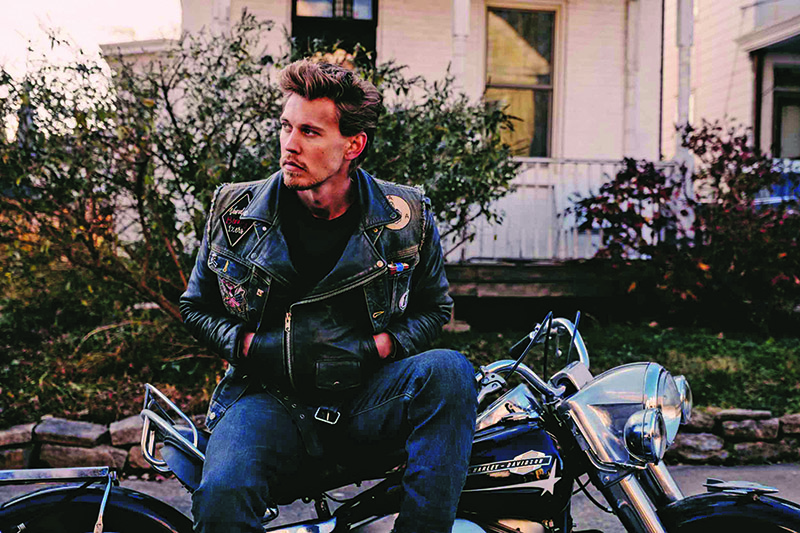

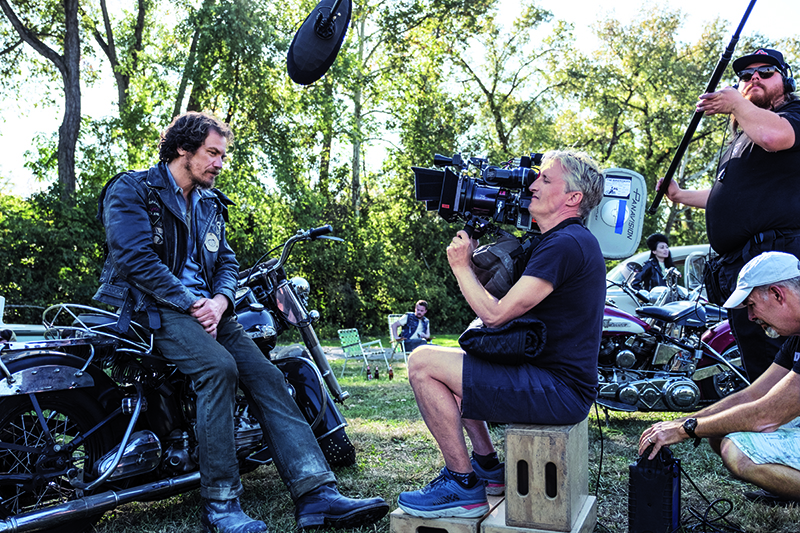

The Bikeriders is a 2024 American drama film written and directed by Jeff Nichols. It tells a fictional story inspired by the 1967 photo book of the same name by Danny Lyon depicting the lives of the Outlaws MC, a Chicago-based motorcycle club. The film features an ensemble cast that includes Jodie Comer, Austin Butler, Michael Shannon, Mike Faist, Norman Reedus, and Tom Hardy.

A common question we’ve all received is the following one: “What’s your favorite show you’ve worked on?” I find that it can be hard to know how to reply to that question. A show can be a favorite for many different reasons. Was it a good script, was I proud of the finished product, did the crew all get along, was it filmed in a fun location, did I overcome the challenges I faced? Not every show will check all those boxes. I’ve had “favorite shows” that were so because of a great crew, but maybe the end product wasn’t top notch. And I’ve done some great work on a solid-scripted show but the working conditions were rough and not enjoyable. I can now say without hesitation that The Bikeriders is my favorite show.

I was already a fan of director Jeff Nichols’ work, so to get to work on one of his movies, and his first one in seven years, was such an honor and truly a high point in my career. Jeff is a director who truly cares about sound, because his movies are all about story and performance. And that’s at the heart of what Production Sound Mixers do—we protect the performance.

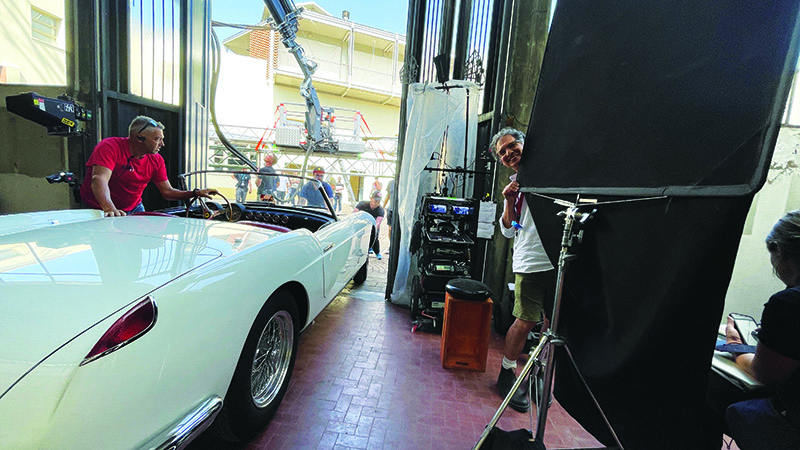

After I had read the script, Jeff and I had a two-hour phone conversation. He has previously always worked with the same Production Sound Mixer (Pud Cusack CAS). Pud was unavailable for this shoot, so Jeff wanted to make sure I was a good fit for the project. We talked about the script and the book, which I was already aware of, and the logistics of recording good sound around very loud vintage motorcycles, and we also talked about how he likes to run his sets, which told me immediately that we would get along. Jeff creates an environment on set that allows the actors to perform at their highest and best abilities. He has a dedicated and loyal crew that returns for movie after movie. They have a history and a shorthand that could feel intimidating to a newcomer, but I’ve never more quickly clicked and fit in with a crew than on this movie. Everyone had each other’s backs, as we were all working to achieve Jeff’s vision, and so no one department’s problems were considered trivial. Everyone was kind, and there was no yelling. I know, it sounds like I’m lying, but I promise you, this show was a joy to work on. The camera crew and I have repeatedly said to each other—we HAVE to do this again.

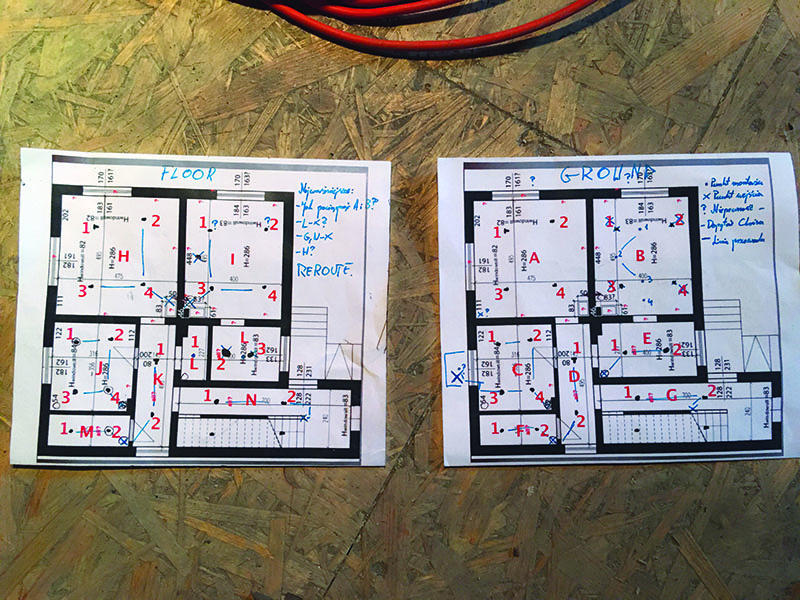

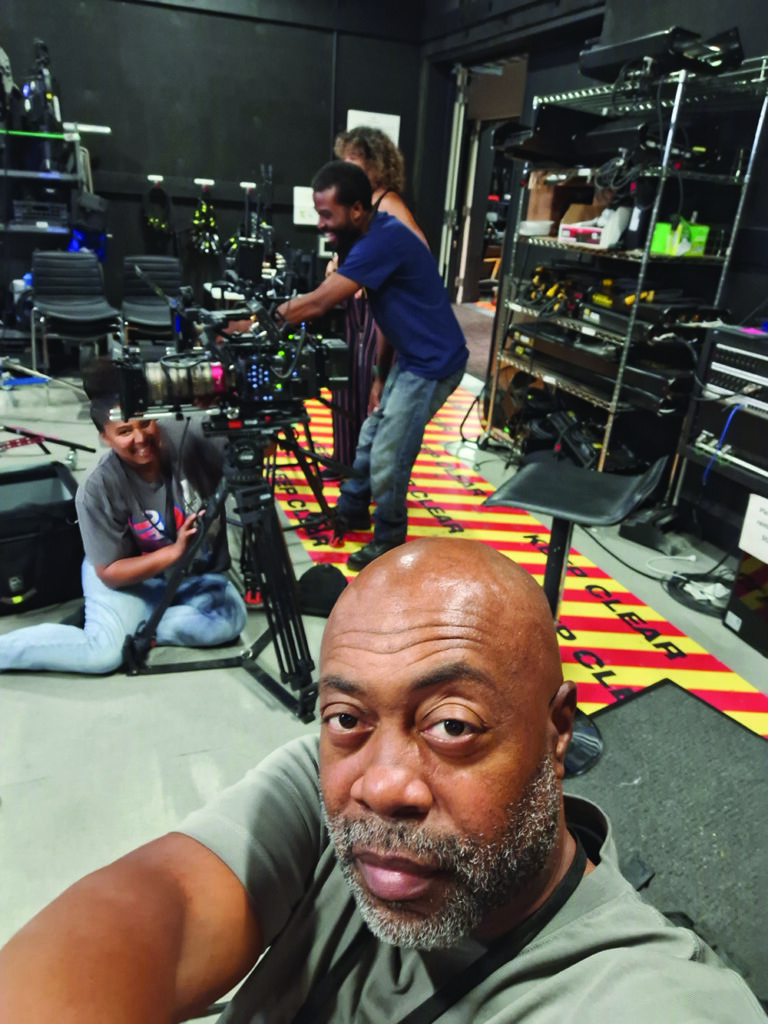

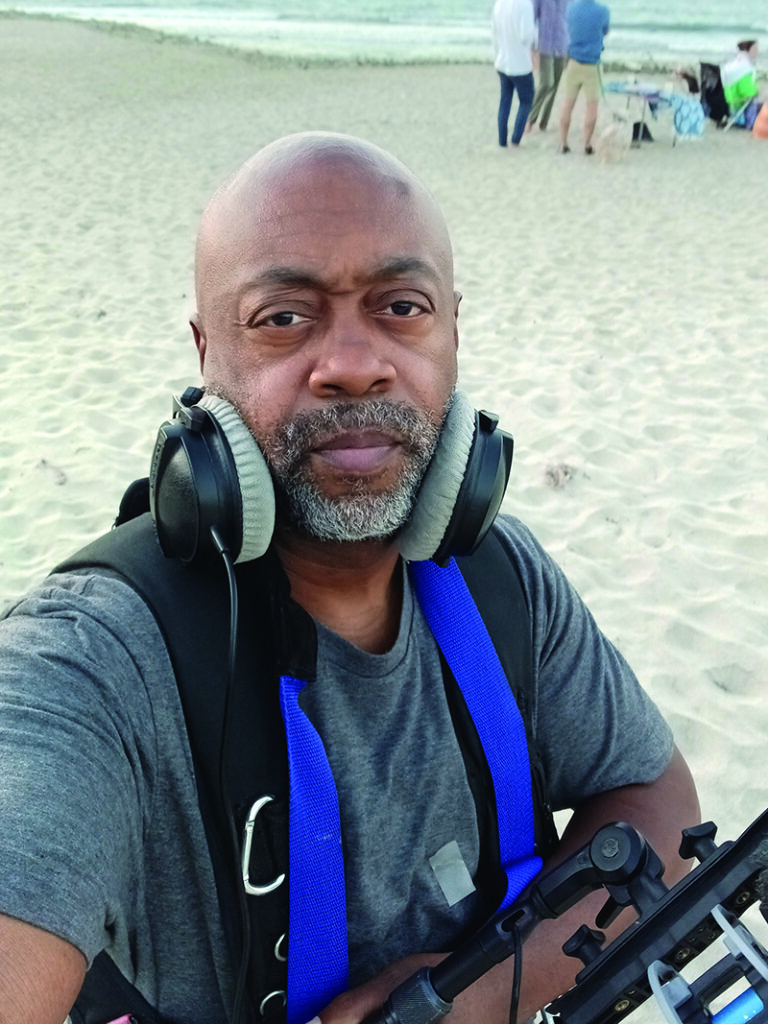

One of the Production Sound Mixer’s responsibilities is putting together the right crew for a show. While I call myself lucky to have a great shortlist of names, as this movie was filming outside of Los Angeles, I would only get to bring a Boom Operator with me, and would need to look into hiring a local, and therefore, unknown to me, Utility Sound Technician. To add to the fun, none of my regular Boom Operators were available (remember when the town was busy…?) which meant I had to also work with a Boom Operator who was new to me. So, all together, that’s a sound crew where none of the members have ever worked with each other. Things could have gone very badly, but the sound gods smiled on me, as legendary Boom Operator David M. Roberts was available and interested. The Bikeriders is a story that takes place in Chicago from the 1950s to the 1970s. Production decided to use Cincinnati, Ohio, as the filming location, which meant I needed to find a Utility Sound Technician local to Ohio. Again, the sound gods smiled, and I found the best utility in all of Ohio (who also just joined Local 695 this past year and so he can now work in both areas!). Zach Mueller made me feel welcomed to the Cincy film community, and he and David got along famously. One of the highest compliments that a Sound Mixer can receive is to be told that they’ve put together a great crew. After all, the boom and utility are the front lines of the Sound Department. From the First AD to the Camera Operators to the Set Costumers—everyone loved David and Zach and never hesitated to tell me so.

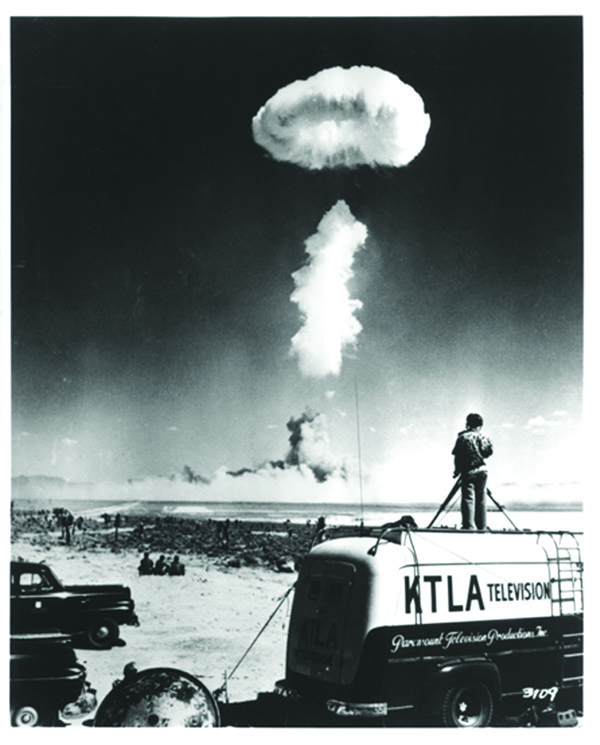

The very first machine I ever recorded sound on was a Nagra 4.2. Those who know, know why I fell in love with sound mixing. And now I was about to mix a movie where a character would be using a reel-to-reel quarter-inch tape recorder as a very important prop in telling the story. While it’s incredibly easy for post sound to manipulate our tracks and make them sound like phone calls, or Nagra recordings, no sound nerd in their right mind is going to pass up an opportunity to record those instances live and as realistically as possible. All of this to say, I bought a Nagra 4.2 for this film. To avoid the headache of needing to digitize the tape recordings, I sent a mix from my Cantar X3 through one of the mic inputs of the Nagra, and then took the line output of the Nagra and fed it back into my X3 as an iso track simply labeled “Nagra.” Now I could send anything I wanted to the Nagra and record and digitize it in real time.

I had made the switch to Shure Axient wireless about a year before I started on The Bikeriders. I cannot express how grateful I was to have their rock-solid technology on my side for this film. There were times in which my receivers would be very far from the transmitters, and either the RX or the TX or both would be in motion on motorcycles or in follow vans. The range that we got with the ADX1 transmitters set to high power of 40mW was not only impressive, but absolutely necessary.

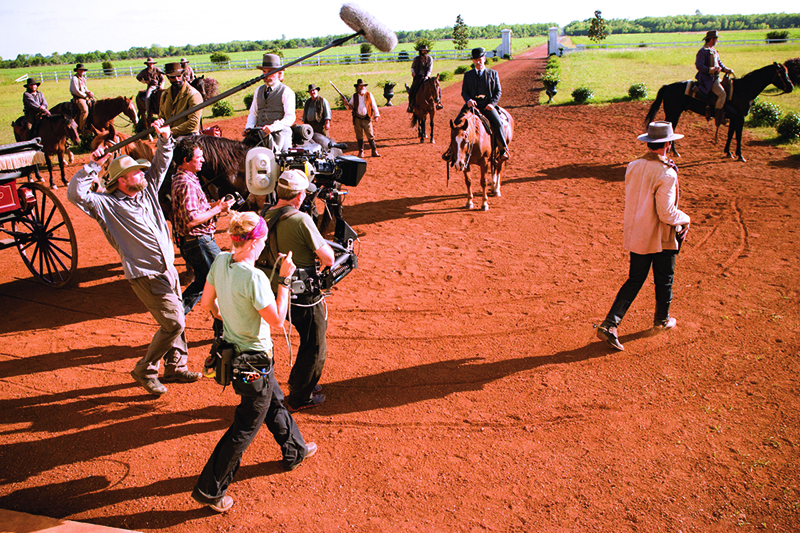

Of course, we were wiring actors, but we had another very loud “character” to deal with—the motorcycles. When the “hoard” as I called all the bikes, was riding together, a boom pointed at the group was next to useless. The bikes were so loud and it just sounded muddy and messy. You couldn’t pick out individual bikes, and so the hoard lacked interest. It didn’t sound as impactful as when you were standing on the road, hearing them in real life. I wanted to record as many separate bikes as possible. As any biker will tell you, each bike has a unique sound, due to how it was built and customized by its owner. I wanted to try and grab those unique sounds, but of course, a day of bike-only recording was out of the question for the schedule. I had to find a way to record the bikes while we were already rolling on other scenes. My solution was to take a Shure ADX1 transmitter and turn on the -12dB pad, as well as set an offset of -5dB. I then used DPA 6061 microphones with the heaviest wind protection we could fit on them. We would use butyl tape (Joe’s Sticky Stuff) and mount the transmitter/mic package on the underside of the bike’s seat, with the mic “pointed” toward the exhaust (as much as one can point an omni-directional lav). The transmitters were also set to the 40mW high-power option. I was able to pick up that transmission even from a follow vehicle quite a distance away, and because of how we’d set the gain staging, we never peaked or had issues with over-modulation. The moment we’d cut, David and Zach would run out, pull the mics, add fresh tape, and pick a new bike to wire. This way, we got as many bikes as possible over the course of every scene.

While working with Jeff Nichols was a dream job for its own reasons, there was also an added benefit for me. Jeff went to college with Will Files MPSE, who is not only an award-winning Sound Designer and Re-recording Mixer, but also a good personal friend of mine. We always talk how important it is to maintain a good relationship between ourselves and our counterparts in post, and in this case, getting to have daily conversations with Will about the challenges we faced, and being able to brainstorm about solutions, could not have been easier. Am I saying that everyone needs to befriend their show’s Re-recording Mixer? No … but it can’t hurt! Will was also insistent that I would get to visit during one of the final mix sessions at Deluxe. I can count on one hand how many times I’ve been invited to sit in on a final mix session, and both times, it’s been with Will. It’s such an educational and eye-opening experience for a Production Sound Mixer to get to see how their tracks are used and how the artistry of the post team really elevates our work. Julie Monroe, Jeff Nichols’ longtime editor, was also there the day I sat in. Nothing made me prouder than when they’d play a scene, and Julie would turn to me and say happily, “That’s your production track!” There was one scene where I pointed out we had recorded a wild track, as I was concerned about the usability of the production track. Julie looked at me and said, “Oh, yeah, we saw your wild track, we didn’t use it, production track was fine.” Other than some walla from our main cast to fill in the bar scenes, no ADR was used. That is a huge testament to my incredible team of David and Zach, and to the magical work Will Files and his team did.

If I sound like I can’t stop talking about what a great experience working on this film was, I won’t apologize. I wish that every single one of us can have the opportunity to work on a film like The Bikeriders. As we still struggle our way through this new year post-strikes, and as we go into our own negotiations, I ask a personal favor that if you can, go see this film in theaters. The work that my team and Will’s did deserves to be watched on the big screen. We do this crazy job because we all want to be a part of making something special, and I am so humbled that I got to be a part of this film.