by Richard Lightstone CAS AMPS

[NOTE: In June 2013, TRANSVIDEO’s holding Ithaki acquired AATON, the French manufacturer of cinematic equipment, now Aaton Digital. Since this time, Jacques Delacoux with his team developed the Cantar-X3, the most advanced on location sound recorder that received a Cinec Award in 2014.]

JP Beauviala, aka “Mr. Aaton,” started the design of the AatonCorder back in 2000; the first working model arrived by 2002. In 2003, the fully functional Cantar-X was released and I still remember the excitement of seeing it demonstrated at NAB that year.

The Cantar-X could record eight tracks and was far from box-like, looking like a modern sculpture, as if from the imagination of Jules Verne. What set it apart was its excellent microphone preamps, rivaling the quality of Stefan Kudelski. Even better, the Cantar was both waterproof and dustproof. Also unusual, were the six linear, magnetic faders on the top and the four screens on its hinged front panel. The inner electronics were flawless and it utilized the excellent Aaton-designed battery system, allowing it to deliver twenty hours of continuous use.

The Cantar-X2 was released in 2006 with major hardware changes, and added software features such as AutoSlate, PolyRotate and PDF Sound-Reports, as well as a Mac and PC software called the GrandArcan that could control all the parameters of the machine. The Cantarem, an eightchannel very portable miniature slide fader mixer, was also new to the market.

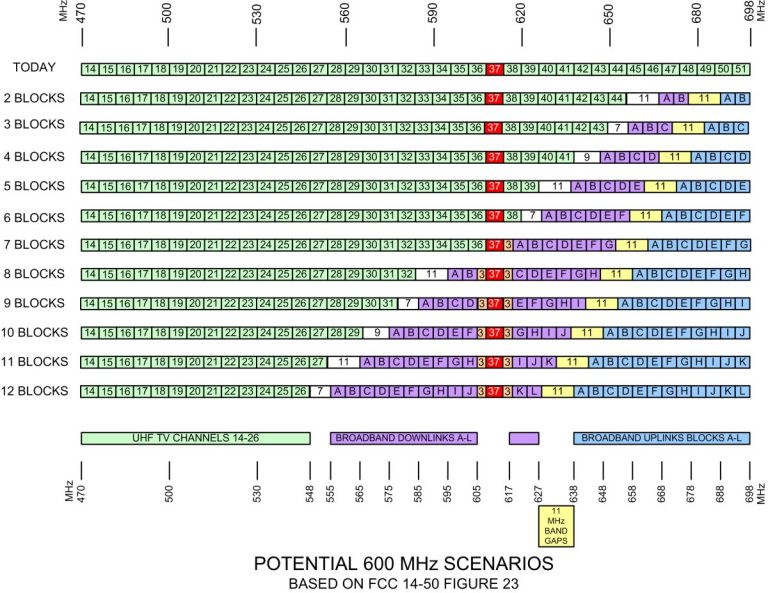

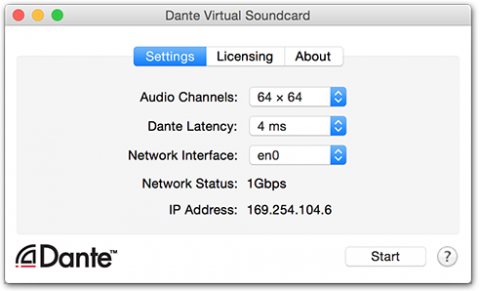

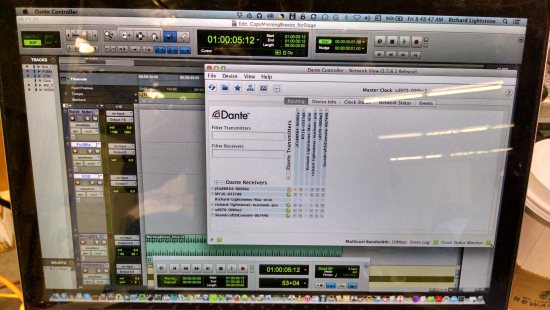

In 2014, Aaton introduced the X3 with major changes in design and features. The X3 is capable of recording twentyfour tracks. Featuring forty-eight analog and digital inputs; eight AES, two AES42, twenty-four via Dante, eight analog microphone inputs and four analog line inputs. As a companion, the redesigned Cantarem 2 is equipped with twelve faders.

Production Mixer Chris Giles was introduced to the Cantar-X2 by Miami base mixer Mark Weber. Chris regales, “When I was covering for Mark on Bloodline (Netflix), a scene took us from a boatyard and then into the mangroves after nightfall. Not a problem for us! Rain or shine, grab the Cantar, put it in a bag with a few receivers, something to cover it when it rains, my boom pole and we are off!”

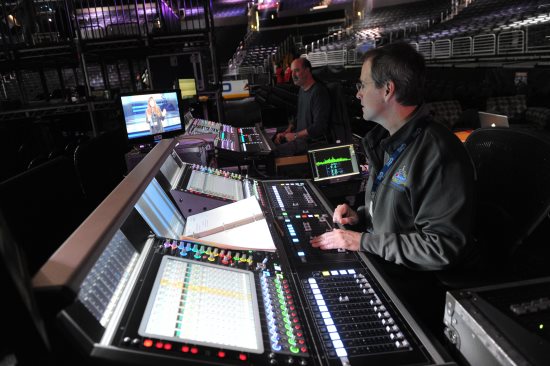

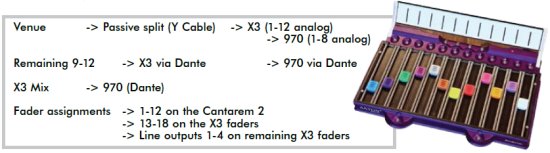

Chris describes the versatility of his Cantar-X3, combined with the Cantarem 2 mix panel in his current configuration.

Whit Norris is a recent convert to the Cantar and his reasoning was twofold; he could interface the X3 with his Sonosax SX-ST8D and record twelve channels with the Cantar’s built-in mixer. Whit describes the other positives: “I could record on four drives at one time all within the X3. There’s the SSD drive, two SD cards and a USB slot. The redundancy is unique to our field.”

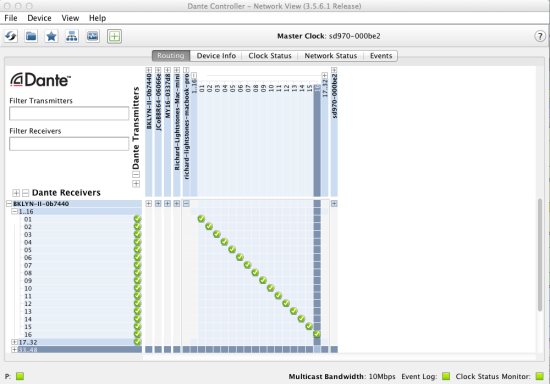

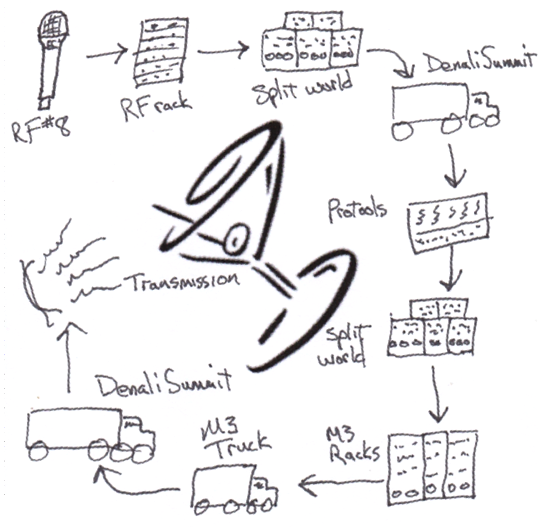

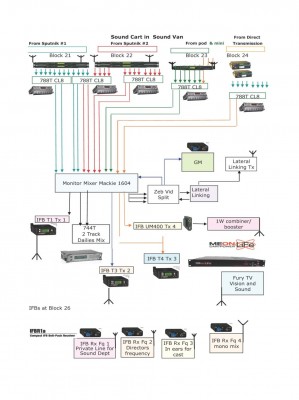

Whit gave the machine a real ‘test drive’ on Fast & Furious 8. With the help of Chris Giles, they came up with a suitable routing plot. Whit assigned the mix to track 1, a combine of the mix out of the Sonosax and the internal X3 inputs. The AES inputs on the X3 to tracks 2-9, from the Sonosax AES outputs 1-8. The mic/line inputs directly in on the X3 are assigned to tracks 10 through 17. The line inputs 1-3 are assigned to tracks 18 through 20 and line 4 from the ST8D Mix out to the mix track on the Cantar.

For the locations in Cuba, Whit wanted a smaller footprint: “I went to a very small SKB case, where the Cantar was the mixer and the recorder. I had ten tracks with the Cantar, using it as a mixer. We needed to be very portable and I could just break the Cantar off and go with it when needed.”

Michael ‘Kriky’ Krikorian recently moved to the X3 and the Cantarem 2. “As a twenty-four-track recorder, I’m not worried about running out of ISOs. I record two mix tracks on channels 1(Xl) and 2(Xr). Xl is at -20db while Xr is at -25db. My wireless mics are assigned to ISO tracks 3-14 and are also post fader to Xl and Xr mix tracks. There is a menu setting that allows you to move your Xl and Xr metering to the far right of the display screen. This aligns metering on the display to match my fader assignments and place the mix tracks separate from my ISO tracks.” Michael continues, “On the Cantarem 2, faders 1 and 2 are boom 1 and 2 respectively, while faders 3-12 are for my wireless lavs. I assign the ten linear faders and the first two line in pots on the X3 as my trims.”

The display screen is the largest of any HD recorder on the market and the brightness range can be controlled for any environment.

The main selector, reminiscent of the Nagra, controls many features of the X3. For example, the one o’clock position takes you to ‘Backup Parameters.’ This function allows you to copy files from one media to another, restore trashed takes or create polyphonic files from monophonic ones. Since its introduction, the Cantar defaults to recording monophonic wave files but it allows you to create polyphonic files to any other media.

Two o’clock is ‘Session,’ which includes the project and which media you record to, as well as the sound report setup. Three o’clock is ‘Technical,’ such as scene & take, metadata, file naming and VU meter settings. Four o’clock ‘Audio & Timecode,’ including sample rate, bit depth, pre-record length and of course, all Timecode settings. Five o’clock is ‘In Grid Routing,’ Six o’clock ‘Out Grid Routing,’ Seven ‘Audio File Browser,’ Eight ‘Play,’ Nine ‘Stop,’ Ten ‘Test,’ Eleven ‘Pre-Record’ and Twelve o’clock is ‘Record.’

There are also six function buttons that take you to numerous shortcuts depending on what position the main selector is in.

Michael Krikorian states, “One of the major positive things I have experienced with the Cantar-X3 is the responsiveness of Aaton when it comes to firmware requests. They listen and respond. When you’re buying a recorder like this, you get the folks that built it, not just product specialists.”

Whit Norris adds, “They have been one of the most responsive companies as far as coming out with software. Despite being in France, Aaton responded to any issues or to anything I wanted to change. They addressed it very quickly and would have beta software within a couple of weeks. But they really were listening to myself and to others on improvements we wanted and acted very quickly on that.”

Michael talks about the sound report features. “I have been using the sound report function on the X3. It gives you the option to lay out your sound report to suit your preferences. You can change and move around your header info, not unlike doing a spread sheet. It lays out your scene, take, file name and tracks in a standard sound report format. I have been debating about using the sound report from the X3 only but for now, I will snap a report as a backup in each recorded folder as I still continue to use Movie Slate.”

One of the criticisms of the early Cantar-X1 and two buyers in North America was its Euro-centric functionality. The design of the Cantar-X3 seems to certainly address this market and goes beyond.

Lee Orloff CAS explains, “Coming to the end of long stretch as a Nagra D user, it was apparent that the writing was on the wall, the days of linear recording in our industry, digital or analog, were numbered. I, like many, were intrigued by Aaton’s new Cantar design. It moved on and off the cart seamlessly, felt good in the hands with its hybrid retro layout and was very easy on the ears.

Early adopters I imagine, started using it for similar reasons. But it never captured a wide audience here in the States. Was it just a bit too French? There were issues that didn’t fit our production workflow, not the least of which was the lack of realtime mirroring, that in the days of slow DVD dailies delivery brought about real challenges for the production mixer. Its native monophonic file format created another one. The beauty of the evolution of the recorder in its current incarnation, is that Aaton has addressed the early design challenges of the first and second-generation machines, keeping the qualities which made it so attractive, while adding current and future leaning functionality in a package with far more intuitive user interface than ever before.”

I marvel at the design team’s logic in being able to put so much and more in one highly technical recorder in Aaton’s Cantar-X3.