by Richard Lightstone CAS AMPS

I met up with Bruce Arledge Jr., in the sound booth for Dancing with the Stars, via Zoom. I thought he was rolling, but Bruce said, “Oh, no, we’re just rehearsing the opening number. It’s all playback. I’ve got the faders open.”

Bruce has been on DWTS for sixteen seasons and is a second- generation Local 695 Sound Mixer. His dad, Bruce Arledge Sr., worked at KTLA, ABC and was one of the first freelance Audio Engineers. Some of Bruce Arledge Jr.’s credits include Grease Live! (2016), Hairspray Live! (2016), and Rent: Live (2019), as the Audio Supervisor.

Bruce began his career as an A-2 and then moved up to a Fisher Boom Operator on videotape shows. In those days they usually had two booms on the stage floor. When he moved on to four-camera live audience film shows, there was no room for the base of the Fisher booms. The boom arms were moved up to the green beds and were mounted on to catwalk stands by Local 80. The booms were locked in place and they no longer had the flexibility to have the A-2’s dolly the perambulator into an ideal position on the stage floor.

After Bruce put in a couple of seasons on Family Matters over at Warner Bros., he started tinkering on an idea to manufacture a device to allow the booms to be moved anywhere in the green beds.

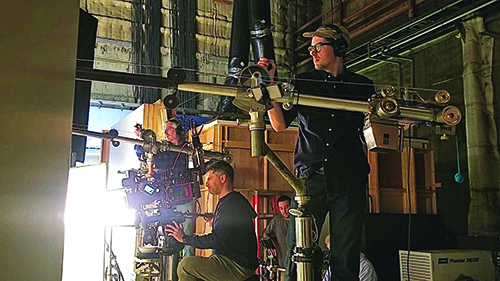

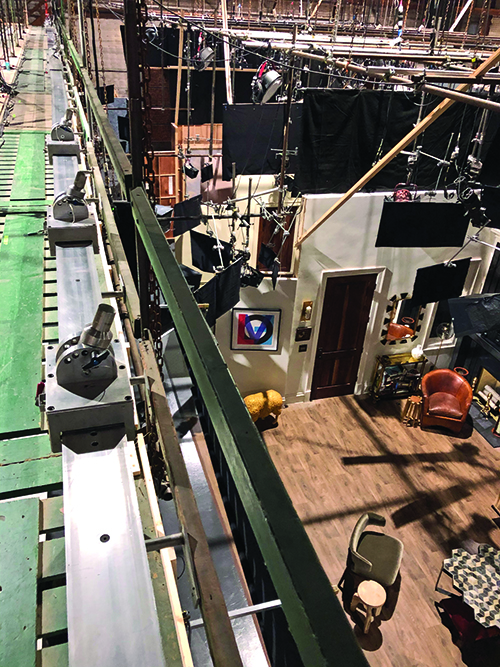

Thus, Boom-Trac was born; it’s a T-bar track system that’s interconnected, and can run along the whole front of the stage above the proscenium. It’s essentially a dolly system that sits on the track allowing the booms to move seamlessly and quietly. You can do on-air moves, while the mic faders are open. The Boom Operator can reposition and adjust angles depending on talent blocking, lighting, and shadow issues. You can move straight up and down or as high as you want allowing the opportunity to move the boom anywhere needed.

In the first year, he got his system on about four shows and it was very well received. Bruce explains, “I had great relationships with all the Boom Operators because, I too was a Boom Operator. We went from four shows, to eight shows, to thirty shows, within two seasons.”

Bruce Arledge’s Boom-Trac is a hands-on operation. “I’m still involved with every setup and strike. I handle all the clients and producers, many I’ve known for thirty years. We have shows at Warner Bros., Sony, Radford, basically wherever there is a four-camera show that needs our system, we install it.”

At the time of writing, Bruce has installs on eleven shows. “We’re just starting to get back into it. In the last few weeks, we have set up new shows and a lot of the shows that went down because of COVID, just kept their stuff up. We’re picking back up right now again. We are doing all of our installs on empty stages. I just want to keep my employees safe and keep the clients safe too.”

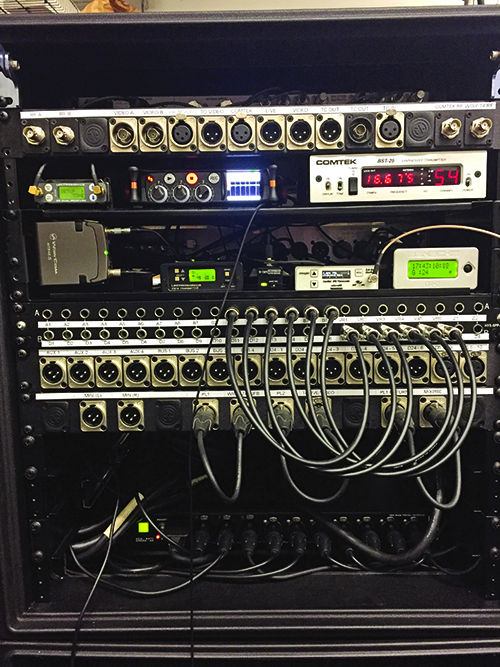

Bruce Arledge’s sound booth for Dancing with the Stars

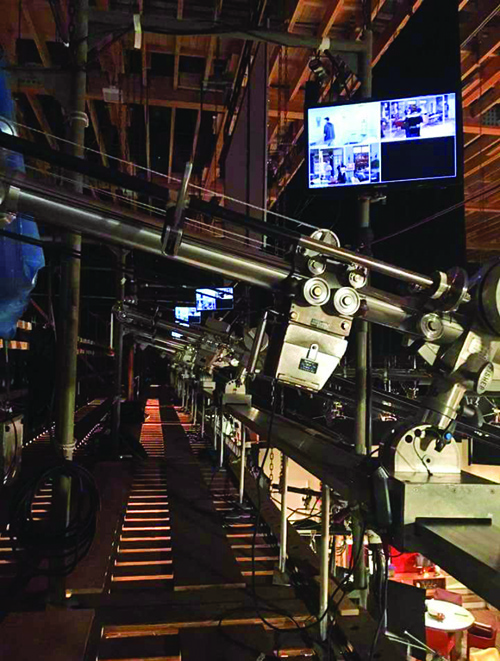

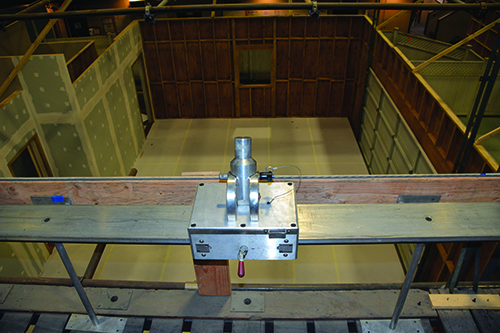

Boom-Trac installed in the perms;

The Calrec Apollo console

Bruce is there for every install and setup of Boom-Trac. “I’m there to make sure that everything’s perfect for the twenty-six-foot boom arms.” Bruce continues, “Because nobody does it as good as I would, I care about it, I’m very hands-on. I know how the device works and I want it to be perfect so when the operator steps up and has no issues.”

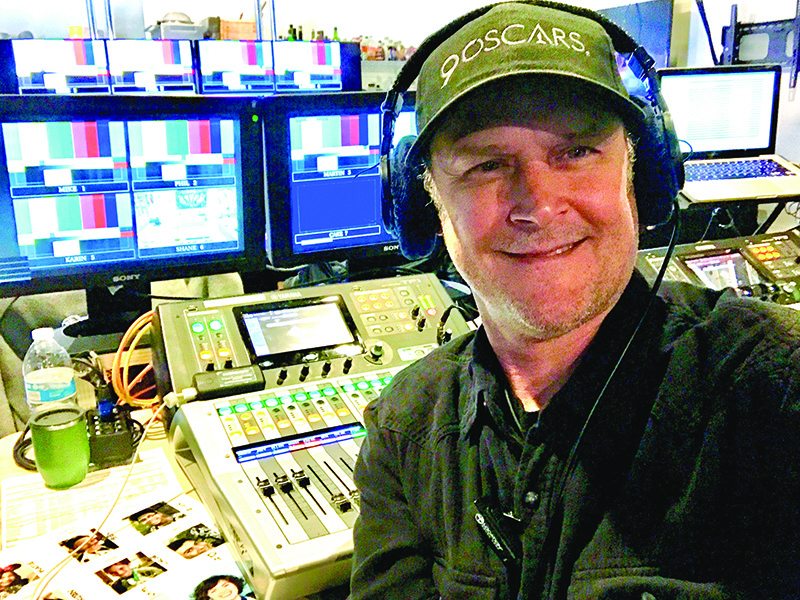

Bruce’s first live mixing experience was on American Idol Gives Back at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium with Elton John, the show received an Emmy nomination. The next year, he was hired for DWTS. “The show is two hours live. That train gets going, and there’s no stopping.”

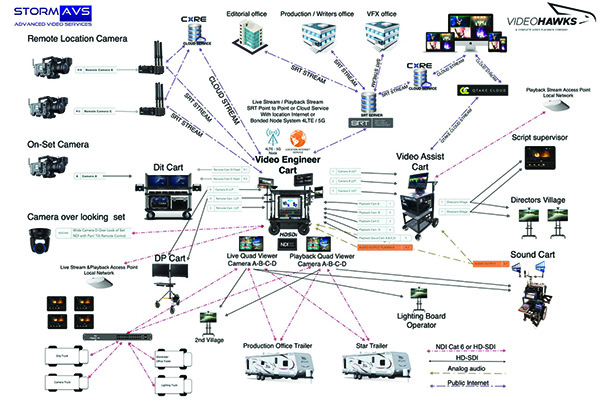

“I have fifty-five channels of RF microphones and about two hundred inputs and over three hundred outputs. It’s not just a 5.1 mix that I send to the network. There is redundant Pro Tools, video tape machines, and everything is sent via fiber to edit. Each mic is isolated, so it’s quite an undertaking. My book of notes is a binder so I can keep track of it all.”

Bruce equates his job to that of an athlete. He is also a surfer, skateboarder, and snowboarder, so he knows from where he speaks. “I love that edge and not everybody could be in the seat that we’re in.” Bruce expounds, “It takes a certain type of personality, some people hate it. Some say, ‘I would not do a live show.’ They don’t want the stress. I love that. That’s when I’m at peace; when I’m sitting there looking at a rundown and it’s five minutes to showtime and the only thing I gotta worry about is the page in front of me, that’s calming for me.”

Bruce always has a backup plan. For example, he’ll have a hardwired microphone in case the RF mic dies. He also relies on his crew of five A-2’s, an FOH Mixer with a Tech, and a Playback Operator. When there was a live band, there was an additional Monitor Mixer, Monitor Tech, and two more A-2’s.

Currently, the show is working under COVID protocols, things have changed. Bruce explains, “In the past twenty-eight seasons, the band has been live on stage but because of the current COVID-19 situation, it has forced us to record offsite. All the dance numbers are recorded Thursdays and Fridays, with the final mix on Saturday. After the band is recorded and mixed, our Musical Director, Ray Chew, is on stage during rehearsal and the live show to make any necessary changes to the tracks. Jose Alcantar, the Pro Tools Mixer, has all the recorded stems to make that possible in real time. The completed songs are then uploaded to a server to allow all departments access. All the tracks are striped with timecode for sync for lighting cues, and SFX. The system allows us complete flexibility and consistency.”

Bruce uses a Calrec Apollo console with fifty-two inputs each on the A and B side, going twelve layers deep, with enough pres and analog inputs to handle two hundred and fifty channels of audio.

During the prolonged hiatus, Bruce used the time to be with his grandkids and his family. Bruce explains, “Everything slowed down. I had my second grandson and I threw myself into helping my daughter out, which I also did with my first grandson, and got to watch him three days a week. That’s what I did, and that was beautiful.”

But Bruce is very happy to be back at work and doing what he loves after his five-month layoff. Living on the edge and delivering a fabulous mix—LIVE!

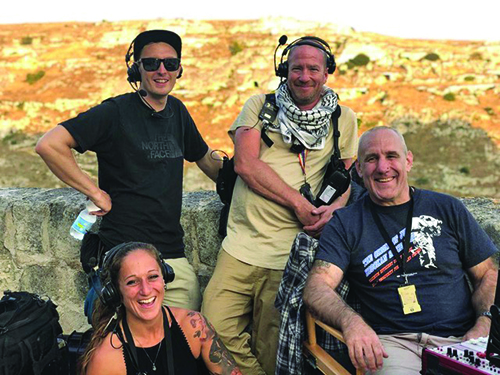

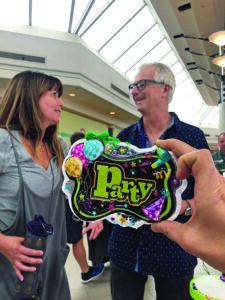

Seated L to R: Bruce Arledge Jr., Steven Anderson.

The Sound Crew

Bruce Arledge Jr. – Live Production Mixer

John Protzko – FOH Mixer

David Vaughn – Playback

Doug Wingert – Audience Sweetener

Jose Alcantar – Pro Tools Mixer

Steve Anderson – Lead A-2

A-2’s

Victor Mercado

Craig Rovello

Brandon Gilbert

Robyn Gerry-Rose

System Techs

Rick Bramlet

Dave Ingels

Pre-recording Music Mixer – Randy Faustino

Monitor Mixers

Butch McKarge

Pete Kudas

Music A-2

Damon Andres

The Equipment

Production Mixing Console

Calrec Apollo

Monitoring

JBL 6328 5.1 system

Multitrack Record

Pro Tools

Sound Devices 970

Playback System

Spot-on redundant System

Desk microphones

4 – Neumann 185

Wireless units –

Provided and coordinated by Soundtronics Wireless

45 – Lavs Sennheiser 5212 w/ Vt-500

3 – Hand mics Sennheiser SK5200

w/ DPA 4018v

Audience Reaction

Sennheiser 416’s

Neumann KM-184’s

Countrymen Isomax Hypercardiod

FOH system –

Provided by ATK (AudioTek Corp.)

Console

Digico SD-5

House PA System Line Arrays

JBL-Vertec VT

W-4 4-way Splitter

Subwoofers – JBL VTX S28

Main PA – JBL V20