by Jeffrey Humphreys

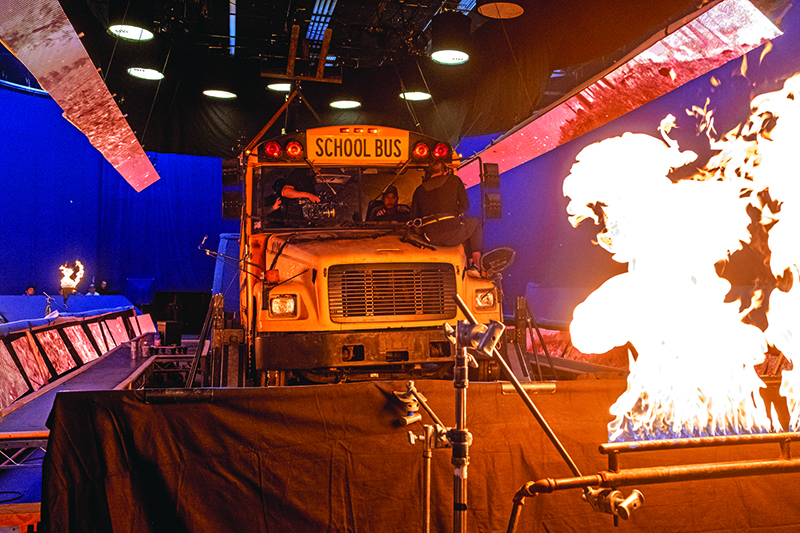

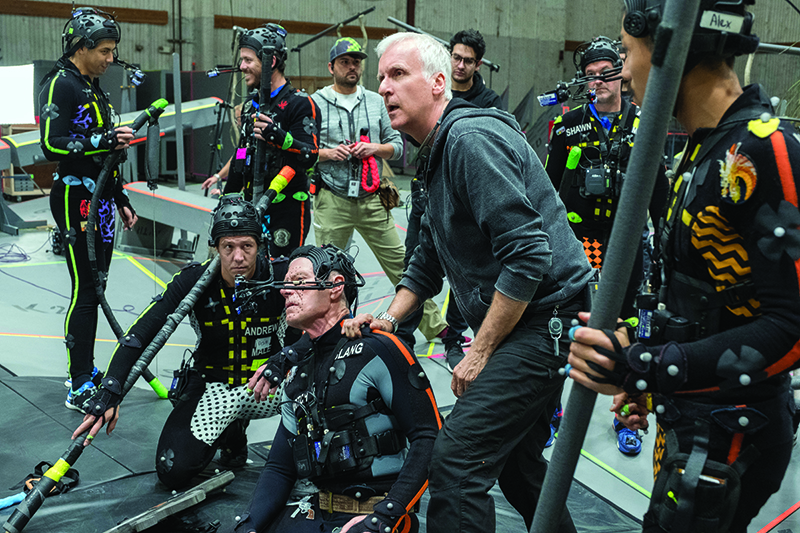

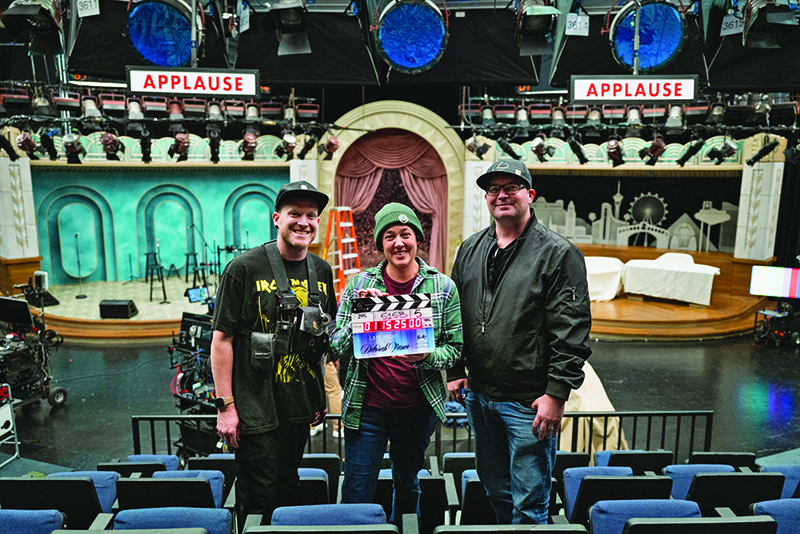

On July 31, 2024, I walked off a movie set for the last time. The film was the most recent Superman, directed by James Gunn. I knew in my heart I couldn’t have asked for a better note to end on. After forty-seven years filled with challenges, adventure, and days that were never quite the same, it was simply time. I look back with nothing but gratitude for a career blessed by the chance to work alongside the most extraordinary people in the world.

One of the first lessons I learned in this business is that we don’t achieve anything alone. Whatever success I may have had was never mine alone—it was the product of the amazing people I met along the way, those who trusted me and allowed me to work with them. The list is long, but three names stand out as pillars not only of my career, but of my life.

Jeff Wexler

As many of you know, we recently lost Jeff, and I count myself incredibly fortunate to have worked with him. We also lost Don Coufal, a dear friend who passed not long ago. When I think about the great production sound teams across the decades, Jeff and Don were the pinnacle—the standard by which all others are measured. Before I met Jeff, to me, he was bigger than life. Then one day, I got a call from him to see if I was available. I remember thinking if I was on the top of Mount Whitney, I would’ve run down that mountain immediately to make a 6 AM call in Long Beach. I honestly didn’t know what to expect when I met Jeff. I really didn’t. But it didn’t take long to see what an incredible man that he was. He was soft spoken but engaging. As a Sound Mixer, he was totally focused, and I mean all the time. Jeff genuinely showed an interest, not only to the people on his crew, but to everyone around him. Jeff retired a few years back and I always kept in touch with him. I called him at least once every month. I had just spoken with him a couple of weeks ago. We lost a legendary Sound Mixer, but more importantly, and sadly, we lost an amazing human being that I will always miss.

Geoff Patterson

I first met Geoff Patterson while filling in for the legendary Boom Operator Randy Johnson on a movie called Little Giants. Randy is one of those amazing people I met along the way. In all my many years as a Boom Operator, I think Randy was responsible for giving me more work than anyone else. He’s not only a great Boom Operator, but a mentor, and a friend, and I’ll always be grateful to him.

Back to Geoff. We were on a makeshift football field at the Burbank Equestrian Center, standing in front of his meticulously engineered sound cart—perfectionist to the core, never compromising, but never obsessive. I introduced myself, as I always did when there was a chance to get in front of a Sound Mixer. I don’t remember exactly what we talked about—probably cramming my whole life story into five minutes—but what stuck with me was simple, Geoff was a great guy.

Years later, another longtime friend, Sound Mixer Beau Baker, told me, “If you ever get the chance to work with Geoff Patterson, take it. He’s the greatest guy ever.” I tracked down Geoff’s number through the union and called him. He told me he had something coming up but had not made crew decisions yet. Time passed, and I hadn’t heard back, so I called again. Armed with Beau’s advice and my impression of Geoff, I knew I wanted to work with him. I rambled, I begged—not just for a job, but for the chance to work with him. I think he hired me just to shut me up. That was The One, a Jet Li action film. It was the first time in twenty years of doing this work that I realized how much fun making a movie could be. Geoff made it different.

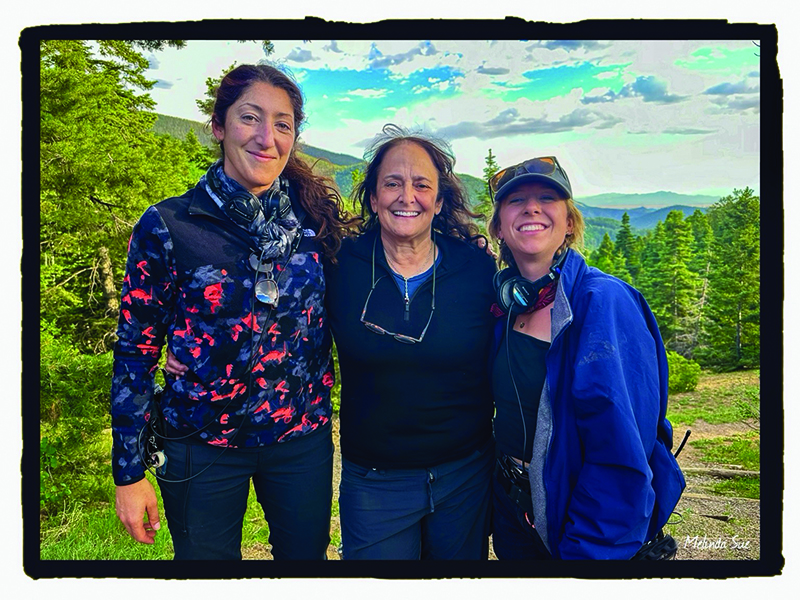

From that moment until I retired, I worked with Geoff on many shows. More importantly, we built a relationship that started with a chance meeting and grew into years of friendship. During the time I lived in Minnesota, Geoff opened his home to me in Los Angeles, whether we were working together or not. There were years we spent nearly every hour of the day together—working, carpooling, sharing a house. Through all that time, not once did Geoff ever treat me with disrespect. Not once, even under the pressures of a film set. For those who know him, you’ll agree, Geoff Patterson is a wonderful man. The kindness and grace you see on set is exactly who he is in life, twenty‑four hours a day, seven days a week.

Not only is Geoff a great guy, he was also a great Sound Mixer. With two Academy Award nominations and multiple Emmy and CAS Award nominations, I don’t think that he ever got the accolades he deserved. It seems that people in our business get recognition because they’ve worked on a number of high-profile projects throughout their career. Geoff made different decisions in his life. He didn’t want to leave his family to go on locations when his two boys were young, so he chose to stay and work in Los Angeles, turning down projects that would take him away. He chose a different path. He didn’t care about any recognition. It was more important for him to stay home so he could run his boys’ track club, and just be with them, than it was to accept movies that would force him to leave town.

Lee Orloff

I think it’s safe to say that most people in our sound community either know Lee or know of his reputation. I certainly knew who he was when he offered me the Boom Operator position on Pirates of the Caribbean 2 and 3. Quite honestly, it was kind of intimidating. My first day working with him involved flying down to the Bahamas and walking out to the dock to board the Black Pearl. I remember the first scene that we did together like it was yesterday. I was on the deck of the Black Pearl, and like most scenes, there’s a lot of people talking. This scene was no exception. But it timed out, and the sun was in the right position, and I was able to boom everything. After the rehearsal, I went down below deck where Lee positioned himself, and he asked me, “What do I need to know?” Rather than go into some long explanation, I simply said, “It’s gonna be great!” I think he wanted a little more out of me by the puzzled look on his face, but I just walked back up to the top deck and we did the scene. It worked out fine. The reason I tell the story is to this day we joke about it. Sometimes I just don’t want to talk that much if I think I have it, which isn’t necessarily the right approach, but for us it worked. Oddly enough, that first day began a twenty-plus-year relationship of trusting each other on a movie set.

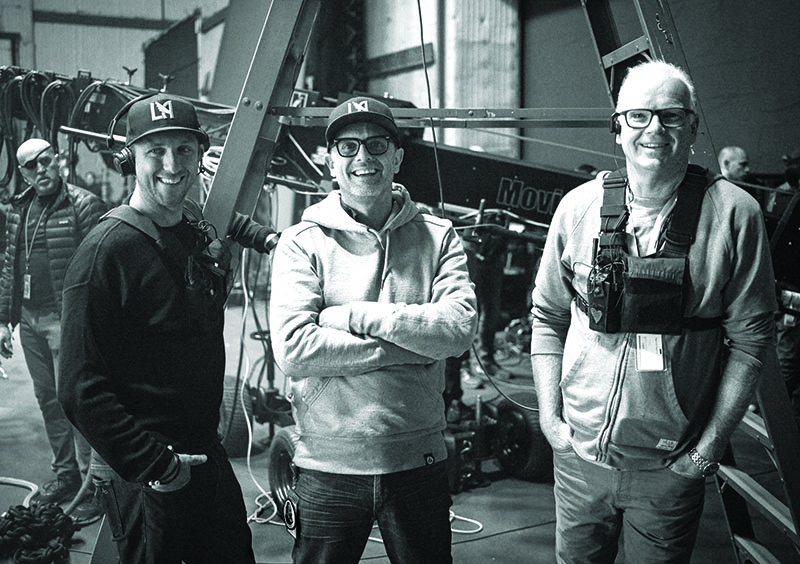

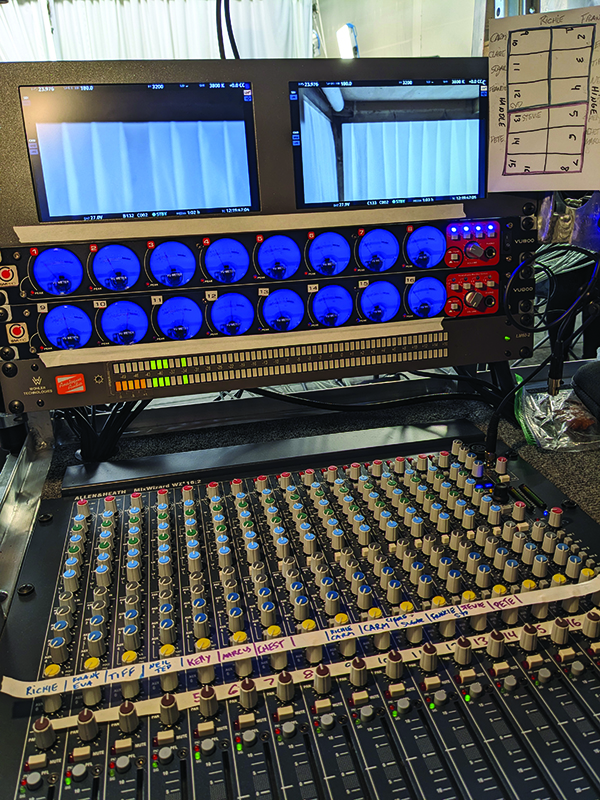

I think what everyone knows about Lee is, he is truly a great Sound Mixer. He is a rare breed with technical knowledge and execution. He can rebuild a Sonosax on the set while mixing five channels of dialog. I’m exaggerating of course, but you get the idea.

Lee had a knack. Lee could sniff out the most difficult movies that would be filmed in the most difficult conditions, working with folks that might be considered challenging to work with. No names of course. Lee didn’t try to steer away from those projects, he went after them, wholeheartedly, and embraced the challenge. I think it’s what made him feel alive. At the end of every day, I think he would reflect on the obstacles that we overcame. I have a photo of Lee that could not be more descriptive of how he approached every day. It’s him sitting, at his station, with a hardhat on, eating a cup of noodles. That’s the kind of guy he is. He brings his lunchpail to work every day, and just does the job. You would think that a guy that has seven Academy Award nominations, with one Oscar, six BAFTA nominations, and a Cinema Audio Society Career Achievement Award, might have a little arrogance about him. But not Lee. Not at all. I don’t think I’ve ever heard him talk about any of that stuff in all the years that I’ve known him. Not once. That’s one of the many things I appreciated about him. And I always respected his humility.

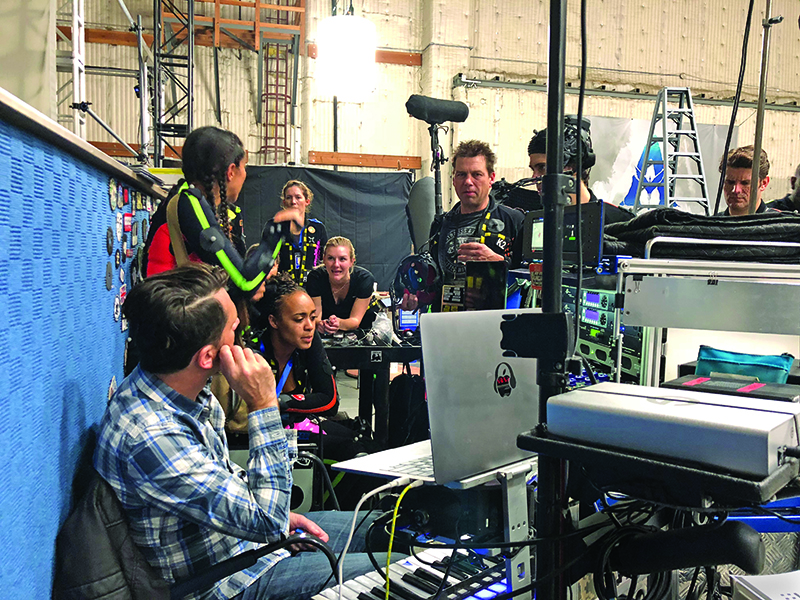

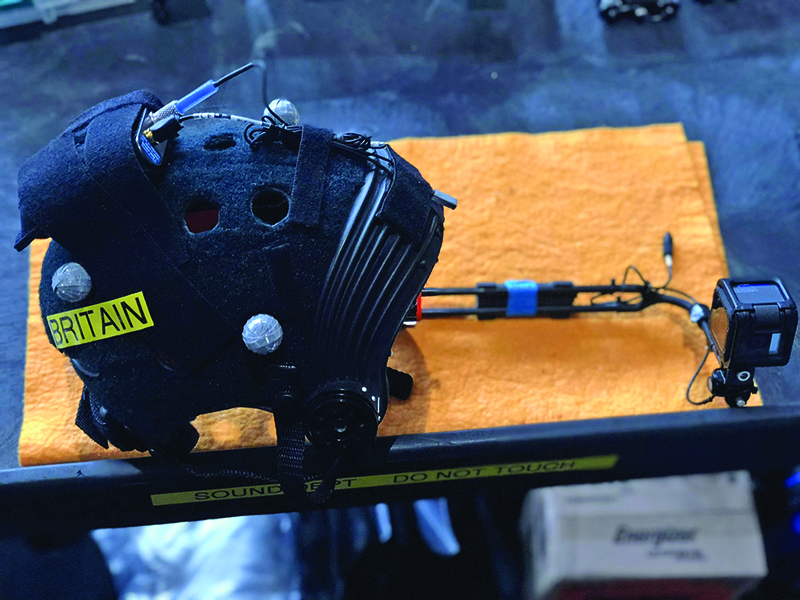

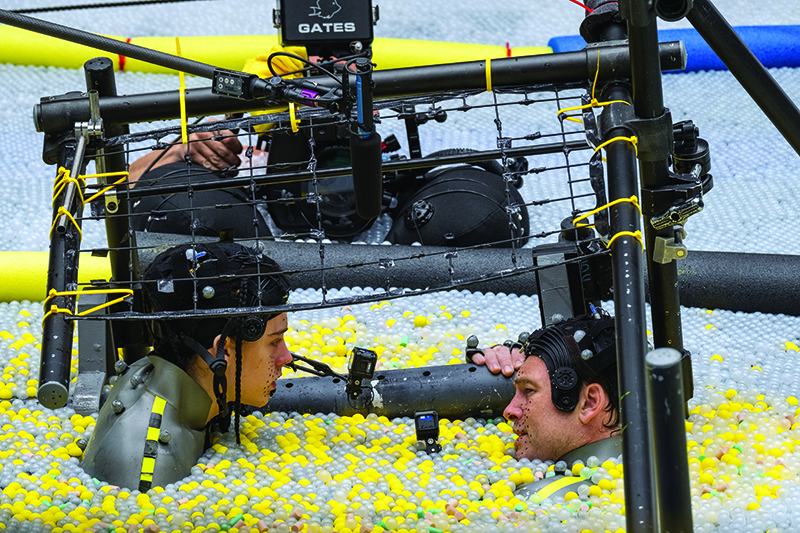

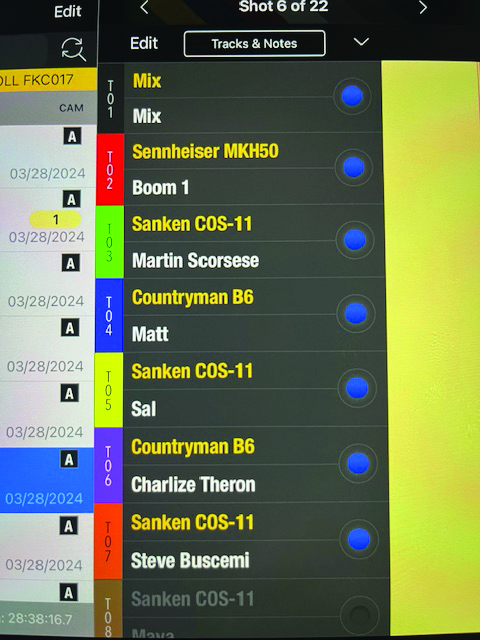

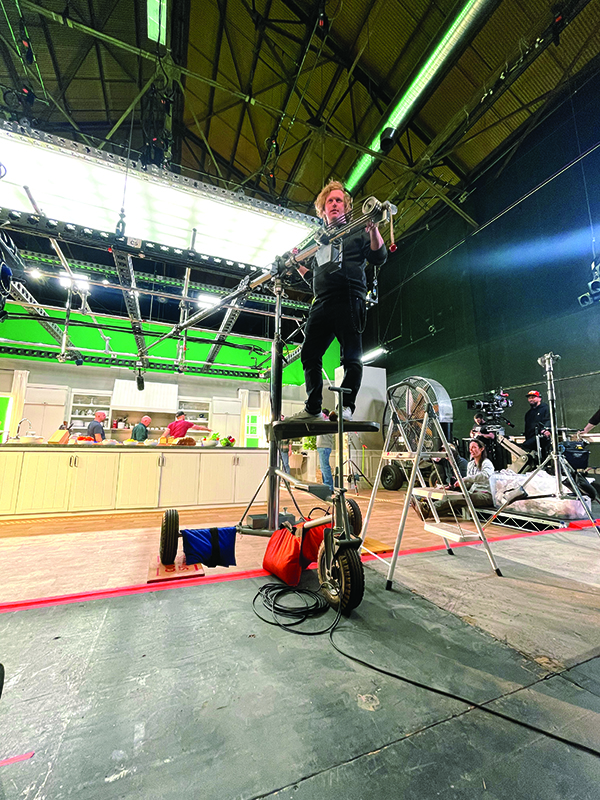

We really did a lot of difficult movies together. Pirates of the Caribbean 2, 3, and 4, The Lone Ranger, Knight and Day, Guardians of the Galaxy 2 and 3, Suicide Squad, Ferrari, Superman, and many others. Each offered their own unique challenges, and Lee always had a plan for everything. He was brilliant at looking at every situation in a unique way and figuring out a way to tackle things.

Now that I am retired, the people that are around me are not in our business, and I often get asked a few questions.

How did you get into the film business?

I had just graduated high school, and I was working at Carl’s Jr. I was probably adding the finishing touches on a superstar with cheese when the manager told me I had a phone call. It was my dad who is the head of the Transportation Department at CBS Studio Center. Even though I hadn’t asked him for a job, he told me I would start the next day as a laborer, Local 724. My call was 6 AM, and the first set I ever worked on in the film business was the original Muppet Movie. I stood there proudly with a push broom, and a shovel, and helped anybody that needed it. As I alluded to, I didn’t get anywhere without somebody I had met. In this case, one of our brothers of Local 695, Larry Ellena, hired me out of Local 724 and into 695 to work in sound transfer. Through a series of unfortunate events, caused by me, but out of the dust, I rose and got into production sound. Of course, I needed someone else for that as well. That was another brother in Local 695, and one of my best friends to this day, Tim Salmon.

Did you go to school for sound?

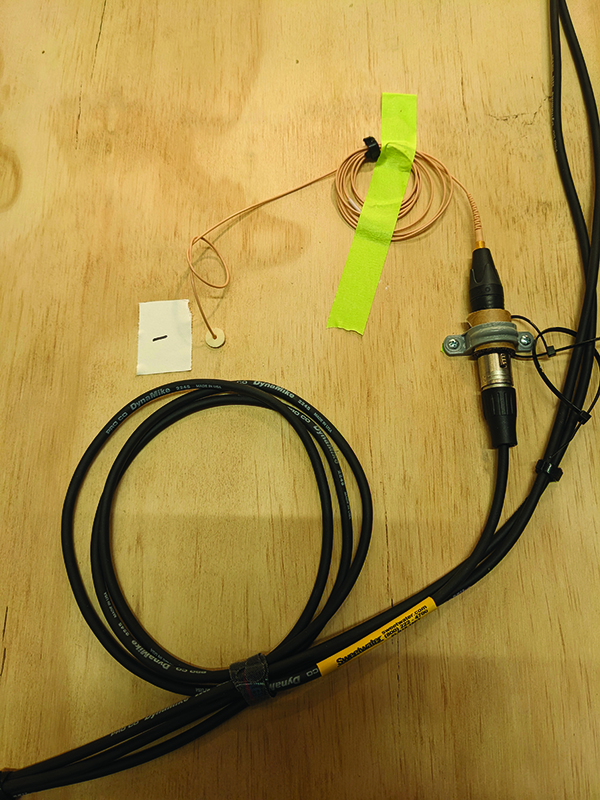

Not at all. Like many of us, it is the proverbial school of hard knocks. I learned by my failures, and did my best trying not to replicate them. I think it’s worth sharing my first day ever in production sound. I was sitting at home when my phone rang and it was a utility person working on a show called Max Headroom, with Joe Kenworthy. It was an emergency call to replace someone on Joe’s crew. I made my way down to MGM Studios and introduced myself. We were filming on a bus set, and I was asked to help set up a plant mic. I had no idea what they were talking about, I’m not exaggerating, I had no idea. I shouldn’t have taken the call because my experience was only in a transfer room. We got through the day, well at least I did, and needless to say, I wasn’t asked to return the next day. Having me on the set was like losing ten of your best men. If Joe reads this, he will have no idea what I’m talking about or who I am, because I don’t think we ever spoke.

My first real job was with Sound Mixer Dean Vernon and Boom Operator Ron Long. These guys were completely old school; everything was done on a Fisher Boom. They had been around so long, they really knew every trick in the book. I don’t think there was ever a Boom Operator as good as Ron Long. It goes back to that old saying, “He taught me everything I know, but not everything he knew.”

What was your favorite movie to work on?

My favorite film experience was Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. I had the privilege of working with the legendary Academy Award-winning Sound Mixer Art Rochester. It was the only film we made together, but it left a lasting impression. Art wasn’t just a great mixer, he was one of the most fascinating people I’ve ever met. His love of the outdoors and his stories about life beyond the set captivated me.

Art’s passion was a huge part of what made Master and Commander so special. When working with a director like Peter Weir, passion comes naturally. I had never worked for anyone like Peter before, and I never would again. The set was a full mock‑up of the British frigate HMS Surprise. Peter made it clear that every person mattered. He knew the names of every crew member, every background sailor, even the animals on board. At the final production meeting before filming began, Peter insisted that everyone attend. He shared his vision for the movie and told us that every job was integral to making something great. I’ll admit, I was skeptical at first, but it didn’t take long to realize he meant every word.

The entire project of Master and Commander was just incredible. From the time I arrived, and I saw the HMS Surprise sitting on its gimbal in the yet to be filled tank in Rosarito, Mexico, to boarding its deck and observing the meticulous attention to detail in the construction of that vessel. Once we began filming, the background arrived, adorned in their perfectly tailored wardrobe, climbing in the rattling as though we were in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. These were professional sailors who knew exactly what they were doing on that ship. Every move they made replicated what would happen if we were at sea in 1805, preparing to battle the French. At the very end, having the opportunity to travel to the Galapagos Islands to film the beautiful scenery, and creatures that are found nowhere else on earth. Every step of the way of that film was challenging but rewarding. I have never been so proud when I wrapped. I believe it was the only movie I didn’t want to end. I think no matter how good the experience is, we all want the job to finish, but Master and Commander was different.

Retirement

Retirement is very interesting. When we retire, there is no fanfare, no gold watch, no dried-out cake from Costco. We just rode off into the sunset, hoping we don’t fall off the horse. Trust me, I really enjoy retirement, but in a certain sense, it’s like hitting a brick wall going one hundred miles an hour. There’s no more call sheets, no more being asked to go into a grace period. I have to make my own breakfast burritos, and if I have a Fraturday, watching a Saturday sunrise while eating Thai food, it’s of my own choosing. I don’t stress out in traffic anymore. If I’m in the sun at one-hundred-degree temperatures, I’m most likely at a beach resort with an umbrella drink. Things are just different now.

In the end, the experience I treasure was never about the project itself, it was always about the people I shared it with. I mean everyone, not only the sound team, but every single person who steps onto the set. We are fortunate to work in a business filled with a wonderfully diverse group of people from different backgrounds, races, genders, religions, all coming together with one common purpose; to make a great film. That spirit of collaboration is what defines each and every project we do. I know I was lucky. I gave everything I had to the film business, and it returned the favor. It gave me all that I asked for. A good living, an amazing adventure, and great people like all of you. Forty-seven years well spent.

I’ll end with the words of the great philosopher, Ted Lasso: “Fairy tales do not start, nor do they end, at the dark forest. That’s only something that shows up smack dab in the middle of the story, but it will all work out. It may not work out how you think it will or how you hope it does. But believe me, it will all work out, exactly as it’s supposed to.”

And it did.