by Simon Hayes CAS AMPS

Production Sound as the Orchestra Pit

How live capture became the emotional engine of the film

I want to thank Jon M. Chu and Producers Marc Platt and David Nicksay for the extraordinary trust they placed in me and in our entire sound and music team. Their unwavering support for the live vocal process, and their belief that original performance was worth fighting for gave us the freedom to build the workflow this film needed. Wicked: For Good could only be made this way because Jon, Marc, and David backed us at every step, creatively and technically, and I am deeply grateful for that partnership.

On a stage musical, the musicians reside in the orchestra pit so as not to distract from the performers on stage and to support the cast in real time. The orchestra breathes with the performers, follows them when they pull on a phrase, gives them something to lean on when the emotion needs a foundation. On traditional musical films, sound and music were treated as separate entities. Music is seen as something that happens when the playback starts and production sound is thought of as the team that captures the dialog.

From the first day of prep on Wicked, and Wicked: For Good (both films were shot together), I wanted to completely remove that separation. There was going to be one integrated sound and music team, whose single job on set was to be the actors’ orchestra pit and to support Jon M. Chu’s storytelling, moment by moment, breath by breath.

That philosophy is how we ended up with the workflow; philosophy came first, the gear followed.

Building a Unified Sound & Music Department

One cohesive team, one heartbeat, one creative language

I noticed a separation between sound and music on my early musicals. Music took responsibility for prerecords and playback, Sound recorded the dialog, with booms and radio mics. You’d share a comms channel and work together on the transition point from dialog to playback, but, fundamentally, you were two different tribes.

That model made no sense at all, especially if you are dedicated to capturing live singing.

Over a number of films, I began to build on an idea that Sound & Music should be treated as the same department on the set and in prep as much as possible. This includes capturing any studio prerecords on the same boom mic and lavs that will be used for dialog capture on the set, alongside the music producer’s choice of vocal mic. This gives a wealth of choices to the Re-recording Mixer even if the project is not going to be live sung! If a project starts like this, it creates a cohesion that finds its way to Picture Editorial and ultimately, to Sound & Music Post and the mix stage.

On the last five musicals I have mixed, Arthur Fenn-Key, 1st AS, has boomed the prerecords and fitted lavs to the actors in the recording studio sending the feeds to the studio’s Pro Tools session.

On Wicked: For Good, our team crystallized around a few key people, many of whom I’d worked with before:

• As Production Sound Mixer, I am responsible for capturing dialog, live singing. and overseeing the entire on-set vocal sound and music workflow.

• Music Supervisor Maggie Rodford, who literally organized the mammoth task both creatively and technically of keeping us all in lock step from a musical standpoint. Maggie was there with me right from the beginning. We built the team together and were in constant communication many months before prep, discussing every nuance and intention of sound and music on the films. I am indebted to her as is our whole department.

• Josh Winslade, our on-set Pro Tools Music Editor, who lived in the middle of the playback world, shaping Greg Wells’s backing tracks, cuing music, and dropping in live elements on the fly.

• Benjamin Holder, Music Associate and Keyboard Player, who became the emotional heartbeat of the system whenever the actors needed freedom of tempo and dynamic.

• Arthur Fenn, Key, and Robin Johnson, my 1st Assistant Sound assistants, i.e., Boom Operators, who were the physical link between the actors and my cart.

• Natassja “Taz” Fairbanks, 2nd Assistant Sound, who became the quiet guardian of floors, leaves, puddles, and anything underfoot that could destroy a performance.

• Robin Baynton, Vocal Editor, who was getting our production tracks into his Pro Tools system and working on them on a day-to-day basis, as well as helping Myron Kerstein with the live vocals and music as we were shooting.

• Dom Ammendum, Music Producer, who was on set with us every single day as our conduit of Wicked musical knowledge and the creative guardian of Stephen Schwartz’s songs and score.

Beyond our immediate team, our work flowed directly into:

• Supervising Music Editor Jack Dolman

• Supervising Sound Editor Nancy Nugent-Title

• Re-recording Mixer Andy Nelson and Re-recording Mixer and Supervising Sound Editor John Marquis

And part of our wider team:

• Stephen Schwartz, Composer

• Steven Oremus, Executive Music Producer

• Greg Wells, Music Producer & Arranger

• John Powell, Score Composer

• Plus, Mike Knobloch of Universal Music, who is an incredible inspiration and support to me. Mike is such an advocate of the live sung musical and I cannot thank him enough.

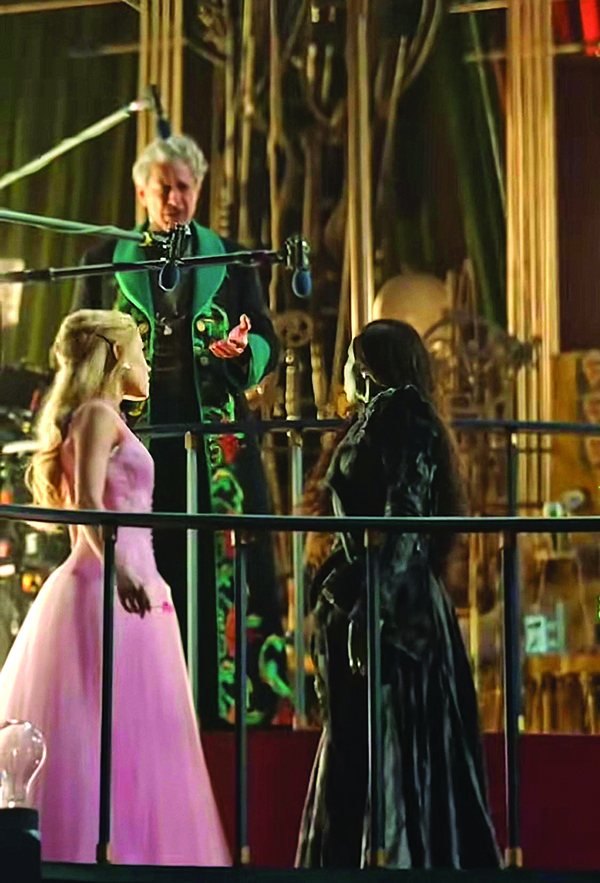

We were not separate departments handling different parts of a workflow. We were one chain, carrying a live performance from Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande standing on a balcony, all the way to an audience sitting in a cinema.

To make that chain work, we had to build a technical infrastructure that treated music playback, live keyboard, production sound, and IEM monitoring as one instrument. That is where the Pro Tools and production sound integration came in.

Pro Tools & Scorpio Integration: The Percussion Section of Our Pit

The rhythmic backbone, the timing grid, the mechanical precision that drove the entire workflow

We built a playback system that behaved like a hybrid between a recording studio and a concert tour, but that also fed directly into my thirty-two-track production recorder in a way that picture editorial could use from day one.

The heart of the music side was a custom playback and Pro Tools rig that Josh and I designed together. It lived on the same style production sound ‘euro’ cart that I use, so the carts are light enough for a single person to wheel around sets and are a two-person lift for staircases. Josh’s playback cart was built around:

• Pro Tools as the main timeline and engine for Greg Wells’s backing tracks

• A Prodigy MC and RME MADIface Pro for high-quality conversion and routing

• MADI and Dante paths between playback and my Sound Devices Scorpio

• Dedicated outputs for:

– Cast IEM’s

– 30kw of JBL on-set speakers where appropriate

– “Thumper” tracks for choreography-only takes

– Stems feeding back into my recorder

That rig was incredibly powerful. It had to behave like a studio in the morning, a concert rig in the afternoon, and a surgical editing tool in the middle of a scene, or even during a take if Jon decided to change the shape of a moment.

From Josh’s Pro Tools system, I took seven discrete stems back into my Scorpio ISO tracks:

1. Mono music

- Music left

- Music right

- Vocal only

- Mono timecode from music, so picture and sound could remain locked

- Sound effects only (embedded in the music where relevant)

- Ben’s live keyboard

I think of that live keyboard stem as the secret weapon. When Cynthia or Ari wanted to drive the tempo themselves rather than be driven by a backing track, Ben could give them exactly the kind of musical support they are used to in a rehearsal room or on stage, and we could still fold that into a fully timecoded, trackable, repeatable film workflow.

All seven of those stems landed as ISO tracks on my Scorpio, alongside the booms and radio mics. My production sound dailies contained the entire musical context of a scene, not just the vocals.

I built two key mix tracks on the Scorpio:

• Mix Track 1 was my vocal and dialog mix. This was exactly what I would want to hear as a Production Sound Mixer: the spoken lines and the sung lines presented as one continuous performance, with no music baked in.

• Mix Track 2 was a mono music mix derived from the Pro Tools stems at a gain that I felt sat correctly under the vocal for dailies and for Jon’s headphones.

For the Picture Editor, Myron Kerstein, this was essential. On most films, early Avid assemblies are built from production sound alone, and music has to be laboriously synced or mocked up later. On Wicked: For Good, Myron and Lara (1st AE) can cut a scene using my two mix tracks, and they immediately have:

• A clean, a cappella version of the vocal on one fader.

• A controllable music bed on another fader, already in sync and already at a unique dedicated level appropriate for vocal and dialog.

If they want to make a quick stereo version, they can reach up to the music left and right stems that are also in my recorder. If they want to elevate the cut for a studio screening, they can timecode lock to Josh’s full Pro Tools sessions later and build a 5.1 music layout. At no stage are they forced to become Dialog Editors, having to reverse-engineer my work before they can even decide if a scene plays.

The Live Keyboard: Our Secret Weapon—The Strings of Our Pit

The emotional bed, the responsive phrasing, the melodic freedom that let the actors breathe and perform

The moment we committed to recording every vocal live, we knew we would often have to replace the rigidity of a conventional playback track with something fluid enough to follow the actors but disciplined enough to hold the shape of a score that Stephen Schwartz had spent years refining. Jon wanted truth. He wanted live breath. He wanted the actors to act their way through the songs rather than deliver a perfect vocal inside a rigid tempo grid. And so, our department had to become, in the truest sense, an orchestra that could follow them.

This is where the keyboard became absolutely essential. From Day One, Music Associate Benjamin Holder stood at the centre of this system with a humility and musical sensitivity that still astonishes me. Ben wasn’t there to lead. His job was to be the safety net beneath Cynthia and Ari, a responsive accompanist capable of changing tempo, tone, intensity, and harmonic feel at the speed of emotion. When Cynthia inhaled, he was already there. When Ari hesitated, he held space for her. When either of them needed to stretch a phrase or soften a moment, he simply moved with them.

The keyboard became the emotional barometer of every take. When Cynthia stepped into a scene with a certain intensity, Ben matched her. When Ari needed space to land a line, he softened the harmonic movement beneath her. When Jeff Goldblum leaned into comedy and theatrical phrasing, Ben pivoted instantly to support the nuance of his delivery. And what made this so remarkable was that the actors never felt the presence of technology. They simply heard what felt like a musical extension of their own intention.

Ben’s playing fed directly into Josh’s Pro Tools session, locked to picture with timecode, and from there into my Sound Devices Scorpio as a dedicated stem. We also captured the MIDI output from Ben’s keyboard, a crucial detail because those MIDI files often became the foundation of the tempo maps that Jack Dolman and the music team later built from in post. That MIDI capture allowed Jack’s team to see precisely how Ben had followed the actors’ moment to moment, creating a truthful map of the emotional tempo before any orchestration was written.

The actors trusted their IEM’s and their ear mix, courtesy of Josh’s rig and my production feed that matched their emotional truth. Sometimes only keyboard, sometimes keyboard with Greg Wells’s backing track, and sometimes a full crossfade into the prerecorded playback track. It was seamless.

Behind the scenes, there was a complex technical ballet happening between Ben’s keyboard and Josh’s Pro Tools session in real time. Josh cued tracks, set up crossfades, updated bar counts, dropped markers, built edits, and monitored timecode. Josh had to feel where the take was going, anticipate where Ben might return to tempo, and manage the invisible transitions that allowed the performance to evolve naturally without compromising the later orchestration.

Ben often had a personal click of his own buried in his IEM to keep the performance loosely tethered to the underlying architecture that Stephen Schwartz, John Powell, and Jeff Atmajian would later need for orchestration and music adaptation.

There were moments when Ben quietly removed his click mid-take, choosing to follow Cynthia or Ari wherever they went emotionally. Those takes were breathtaking. Wild, free, honest. But whenever he could, Ben kept the click in his ears.

This ultimately is why the keyboard mattered so much. It allowed us to preserve the truth of performance in a genre that has historically relied on the safety of lip-sync. It allowed Cynthia, Ari, and Jeff to act their way through songs without feeling constrained by tempo grids or technical expectations.

Across the wider rig, we carried a huge array of stems. Mono music. Stereo playback. Vocal-only stems. Thumper feeds for chorus timing. The keyboard stem. MIDI. My production mix. And each of those mixes could be routed independently to different departments: lighting for cue timing, playback for monitoring, choreography for spatial alignment, Camera Operators for movement synchronisation. Every member of the crew was listening to a version of the moment that supported their job. This is why I say production sound became the orchestra and conductor: our mixes became the heartbeat of the entire film set.

With the four months of prep and year of shooting, that is exactly what the Sound & Music Department became, the support system, the quiet machinery behind the emotion. The instrument that made the impossible possible and allowed this film to be made the way Jon Chu always intended: truthfully, musically, and with the full emotional weight of live performance.

The IEM System: Making the Invisible Audible

To give the cast the kind of support a pit orchestra provides on stage, the IEM system had to be both powerful and invisible. Wicked: For Good wasn’t a concert film, so the presence of an in-ear monitor or an earwig had to disappear completely. Costume and Makeup were essential collaborators from Day One. Every IEM cable and shell was colour-matched for the individual actor. Cynthia had green IEM’s painted to match her exact Elphaba shade; Ari’s were blended to her skin and makeup tone. On wider shots, the IEM’s vanished entirely. On mid-shots and close-ups, VFX painted them out only where absolutely necessary. We worked with PureTone in the UK to create custom-moulded IEM’s and custom earwigs for our principal cast. That achieved two crucial things:

They fit deep and securely in the ear canal, so when Ari was swinging from a chandelier in “Popular” or when Cynthia was flying through the air in “Defying Gravity,” the units didn’t budge.

They protrude less, making VFX paint-out far easier—and on wider shots, often unnecessary.

Inside those IEM’s they heard:

- Ben Holder’s live keyboard

- Greg Wells’s backing track

- A blend of their own voice and their scene partner’s voice

- A version of my boom/lav production mix emphasised for emotional clarity rather than technical neutrality

From a signal perspective, we used two tiers of in-ear support:

• Full-range IEM’s (Sennheiser EW IEM system) for serious live singing—capable of carrying Greg’s full-bandwidth backing tracks, the live keyboard, and their personal vocal blend with proper bass extension.

- Earwigs for moments that required only timing cues or simple guide information—no full-range fidelity, no cable from pack to ear, extremely low profile and often requiring no VFX paint-out.

Every principal actor had a personal mix. Before a take, you’d see Arthur standing beside the actors saying, “Give us a level—just a line,” and Josh would tweak their vocal level in the IEM against either keyboard or track so that emotionally they were exactly where they needed to be. And when they reached for a note emotionally, everything in their ear should rise to meet it—invisibly.

Building a Technical System That Supported Creativity

None of this integration mattered if the technical system couldn’t handle it. Every part of the chain—from Ben’s keyboard, to Josh’s Pro Tools rig, to the MADI system, the Scorpio, the booms and lavs had to behave like one instrument

That required:

• Zero perceptible latency

• Absolute timecode accuracy

• Redundant routing paths

• Seven discrete music stems feeding dailies

• A playback rig that could keep up with rapid camera moves and location shifts

• A system stable enough that Josh could edit on the fly while I was capturing live vocals

This wasn’t a normal musical workflow. It was a hybrid of theatre, live broadcast, studio recording, and feature film production sound. And it only worked because every person in the chain understood not just their own role but how their choices affected everyone else.

Capturing the Ensemble: Thumper Tracks and Real Footfalls

The crowds of Oz are characters in their own right, and the ensemble numbers needed their own live strategy.

The problem with chorus work in musicals is that on set, you are dealing with:

Massive choreography and footfall

Mixed abilities as singers; some are world-class dancers first

A lot of potential set noise

We took a hybrid approach. We recorded ensembles live wherever it made sense, knowing that the production would also bring in incredible ensemble singers from the stage show to support and sweeten those vocals in Post. But I was determined that the physical sound of the set would remain real: the stomping, the desk slams, the movement of bodies in the space.

That is where the “thumper track” came in. We would take the sub-bass from Greg’s backing track, filter out everything above around 38 Hz, and play that back to the dancers. They would feel the rhythm from the low frequency energy that could later be removed completely with EQ and noise reduction.

Choreographer Chris Scott would count them in: “This one is just for sound. No voices. One, two, three…” and we would record pristine chorus footfalls, table slams, and body movement in tempo.

Monitoring Like a Film Mixer, Listening Like a Dialog Mixer

As we shot, almost everyone on the shooting floor wore headphones. Every camera movement and lighting cue was motivated by music. Everyone on the crew needed to hear, and music rarely came out of speakers unless we were shooting huge chorus numbers. What they heard was my dailies mix: live vocal from the booms and lavs, balanced against a mono music track. That way Jon, the Operators and Grips, Choreographers, and Producers could all feel the shape of the scene as it would roughly appear in the cut.

What I listened to was slightly different.

On the first take of a setup, I would listen in context, with music, and set a relationship between vocal and music track that I hoped to keep consistent for the scene, so that Myron’s dailies would have stable levels. Once I was confident that balance was right, I would switch to listening a cappella, with the music often out of my monitoring.

There are two reasons for this:

- Music hides problems. Clothing rustle, a noisy shoe, a generator that has mysteriously appeared behind set, a leaf crunch that looks lovely but sounds like a crisp packet. With music in my ears, those issues can sneak past; with only vocal, they stand out.

- I treat live singing as dialog from a production point of view. It demands the same forensic care. I want to hear breaths, mouth noise, the real acoustic of the space, and I want to know exactly what is under every syllable. That mindset carries through all the way to Andy and John on the dub stage. Andy does not treat “dialog” and “vocal” as separate species. For him, as for me, it is all performance.

Recording “For Good”—Leaves, Puddles, and a Six-Mic Duet

If Wicked: For Good had a single scene that embodied the entire philosophy of the film, it was the balcony sequence for “For Good.”

On paper, it is a simple idea: two friends saying goodbye. In practice, it is a delicate blend of dialog, freeform singing, tightly structured musical material, and camera choreography, all set on a balcony that needed to feel like a real autumn evening, not a soundstage.

Real Leaves, Real Puddles, Real Wind

Before we even began to talk about how we would record the vocals, we had to understand what Nathan Crowley’s production design and Jon’s visual language required.

Jon’s vision of Wicked and For Good was built around vast real sets. Nathan’s stunning designs were built by real craftspeople and artisans. They did not want a CGI balcony with digital leaves and simulated puddles.

Those elements are beautiful for the eye. For sound, they are treacherous.

Crunching leaves underfoot and water squelching in shoes are exactly the sort of mid-band transient noises that fight the same frequencies as the human voice. Add wind machines, and you have the classic recipe for a scene that “looks great but will all be ADR later.”

We were not prepared to accept that trade-off.

Working with the Special Effects team, led by Paul Corbould, we deployed the Silent Wind system that we had refined across the show. Instead of parking huge fans on the stage, we kept all the noisy machinery outside the soundstage and brought the airflow in through stage walls with runs of flexible twelve-inch tubing, each handled by an SFX technician who could aim and feather the airflow with great precision.

What we heard on the mics was not mechanical motor noise; it was a broad, smooth “shhh” of air movement and the sound of leaves shifting.

We adopted a very simple rule:

• Only put leaves where the camera can see them.

On a wide shot, you might see a carpet of leaves stretching to the back of frame. On the reverse, that area may not be visible. We became ruthless about clearing any part of the floor that was not in shot.

This is where Taz Fairbanks came into her own. Shot by shot, lens by lens, she would liaise with the camera team, look at the monitor, then quietly sweep leaves out of the zones that were off-camera, while SFX kept them alive in the areas that mattered visually.

The same was true for the puddles. Visually, they sell the idea that it has been raining, but water and shoes are not friends of live vocals. Every time the lens went tighter, Taz and the art and props teams would go in, mop out the puddles that were now out of frame, and leave only what was absolutely necessary in the composition.

You cannot say you care about original performance and then allow unnecessary noise sources to exist in parts of the set that the audience never even sees.

Beginning as Dialog, Behaving as Song

“For Good” does not start like a “musical number.” It begins like a conversation between two people on a balcony.

Visually, Jon and DP Alice Brooks approached the early part of the scene exactly as you would treat a dramatic dialog sequence. We were largely on Steadicam, floating with the actors as they walked and talked, with the camera weaving in to find their faces.

Technically, I treated the opening like dialog too, but with one crucial difference: I knew that at any moment, Ari or Cynthia had the freedom to step into singing at any given moment, and I had to be ready.

We were using Schoeps CMD 42 digital microphones with MK41 hypercardiod capsules on the booms, sending AES straight down cables to the cart. That gave us an incredibly clean, modern boom sound with all the transient detail we needed, and a consistent digital path right into the Scorpio. On the early beats of the scene, Arthur and Robin were routinely working as close as they could; twelve inches above the actors’ hairlines on wider framings, down to three inches above the hairline on tighter shots, always dancing around the Steadicam.

From a sound perspective, the most interesting thing about those opening passes is that the performances were not locked.

Cynthia and Ari made a creative decision to allow certain words, certain lines, to just slide into singing, depending on how they felt in the moment. On one take, a line might be spoken, on the next, it might soften or swell into melody.

To support that, both actors wore IEM’s from the start. They knew that if they felt compelled to sing a word or a phrase, Ben Holder would be there, following them on the keyboard. Sometimes he would only give them a single note or a tiny fragment of harmony, just enough to catch the emotional weight of what they were doing. But the key point is that his job was not to lead; it was to follow.

Technically, the workflow at this stage was:

• CMD 42’s providing our primary vocal capture.

• DPA 4061 lavaliers on each actor as backup and as an option for some angles.

• Ben’s keyboard feeding Pro Tools which in turn fed the IEM’s.

• My dailies mix presenting the scene to Jon as an integrated whole.

Creatively, the opening is already a piece of live sung cinema. We just have not formally “started the song” yet.

Day One: Crane Day, No Booms Allowed

Once we moved deeper into the body of “For Good,” Jon and Alice made a choice that would reshape my approach to the scene. They wanted to release the cameras from the balcony edge and let it swoop and drift around the space using two Technocranes.

The moves they designed were beautiful: big, sweeping passes that would start at the edge of the soundstage and sail in over the balcony, finding the actors in mid-shot and then retreating back out to reveal the world, and feel the song open up.

There is simply no safe harbor to place a pole that will not end up in the shot, and even if you manage one pass, the crane move will have changed on the next. Day One of “For Good” would be lavalier-only for the singing sections. We ran two DPA 4061 lavaliers on each actor, each feeding its own transmitter and ISO track.

There were two reasons for this:

• Technical redundancy. If we took an RF hit on one transmitter at a critical moment, we had a second, entirely separate capture of the same performance.

• Creative flexibility. We did not stack the mics on top of each other. We placed one on the left chest and one on the right. With a left and a right, one of those mics will always be favouring the direction of the voice.

Incredibly dynamic performances like Ari and Cynthia’s do not sit neatly in a grid. There are phrases where one of them sings a little softer, one syllable that falls away because of emotion or breath. With four lavs in total covering the duet, Robin can look at a word where, for instance, Cynthia drops slightly under Ari and ask: Which of the four mics has the best capture of that exact syllable in that exact head position?

This is what I mean when I say that choice is king for live vocals. You do not ask for more microphones because you are unsure. You ask for them because you are certain that the performance is unique and that it deserves to be sculpted from as many angles as possible.

The DPA’s sounded beautiful, and because of the double-mic strategy, I never had that creeping anxiety of “if something goes wrong here, we have nothing to fall back on.”

During the day, especially once we hit the harmonic duet toward the end of the song, it was clear that we were dealing with something very special. When Ari and Cynthia start to mesh their voices together on that balcony, you feel that they are not just singing lines; they are essentially becoming one instrument. From a mix perspective, that is wonderful and terrifying in equal measure.

Day Two: Extending the Balcony and Bringing the Booms Back

At the end of Day One, Jon looked at those crane passes and said something that changed the way we approached the rest of “For Good.” He was happy with the scale, but he wanted to lean further into the intimacy of the performance.

He wanted the audience to feel as if they were standing on the balcony with Elphaba and Glinda. To do that, he needed the camera to physically get closer and to be able to move around the actors in a fluid, human way.

The solution was to extend the balcony. That change had a knock-on effect for sound: Suddenly, we could bring both the booms back in.

On Day Two, we kept the two DPA 4061’s on each actor, exactly as before. But now, on top of that, Arthur and Robin Johnson came back into play with the CMD 42 booms.

Because the balcony extension gave everyone so much more space, the booms could be in the air above the Steadicam, often coming down to hairline distance in the tightest close-ups. In wide or moving shots, they might be at twelve inches; in the key emotional moments, they were almost in line with the actors’ foreheads.

What made this day special for me was watching Arthur and Robin turn the act of booming into choreography.

They did not simply stand “on their” actor all day. They were constantly trading responsibilities. Sometimes Arthur would be on Ari, sometimes on Cynthia. Sometimes they would swap mid-take as the geometry of the shot changed. Behind the cart, I was keeping meticulous notes of these swaps so that later, Robin and Nancy would know, for any given beat, which boom was favouring which performer.

All of this built toward the final duet section, where the girls are standing incredibly close to each other, nose to nose, singing harmonies that are already at the deepest emotional level without anyone adding reverb or score.

Initially, I considered simplifying the situation. With the actors that close, it is very tempting to say, “Let’s just put one central boom between them and let that take over.” A single mic would certainly have picked up both voices beautifully.

Instead, I asked Arthur and Robin to play their booms so that the capsules were an inch apart in the air, one very slightly favouring Ari, the other very slightly favouring Cynthia. The microphone mounts were almost touching!

The tracks we now had:

• Boom A: CMD 42, MK41, focussed a touch more to one actor

• Boom B: an identical chain, but with that tiny emphasis on the other actor

The reason that matters is that when the harmonies lock and the girls’ voices start to intertwine, there will always be phrases where one is fractionally softer or rolled off because of the angle of the head or the emotional delivery.

Combine that with the four DPA’s and you have six world-class microphones covering two world-class voices in the most important duet of the film.

“For Good” as One Performance: Nancy and Robin with a Singular Dialog and Vocal Editorial Collaboration

If you go right back to the start of “For Good,” it begins life as dialog with moments of spontaneous song. By the end, the two characters are in full vocal flight.

For editorial, that raises a philosophical question: Where does “dialog editing” stop and “music editing” begin?

On Wicked: For Good, the answer is that there is no dividing line, and on “For Good” in particular, that is where the partnership between Nancy Nugent-Title and Robin Baynton became something very special. They approached “For Good” as one continuous performance.

They worked together and treated the scene as a single piece of acting that just happens to move through different kinds of vocal delivery.

The result is that you can watch “For Good” and never once feel that the mix has “stepped onto a stage.” The words that are spoken and the notes that are sung feel like they were born in the same breath, in the same place.

From my perspective as the Production Mixer, this is the payoff for all the choices we made on set: double-miking, half-inch boom spacing, Silent Wind, leaves only in frame, puddles mopped as soon as they are not needed.

The Cost of Truth: Collaboration Versus Lip-Sync

When people ask why we bother to go to these lengths to capture live vocals, I often talk about the creative cost of ADR compared to the financial cost of VFX paint-out. With live vocals, you ask a lot more of the crew. You ask Special Effects to move their machinery outside and invent a unique Silent Wind system for the movie. You ask Art and Props to constantly lay and remove leaves and puddles. You ask Costume to find ways to hide two transmitters on each principal without compromising comfort or silhouette. You ask VFX to budget for the removal of visible mics and IEM’s, not as a last-minute fix but as a planned, creative choice to preserve performance.

You ask Camera to coordinate with you on every pass. You ask your Boom Operators to learn choreography as complex as the dance numbers. You ask your Second Assistant to live in a world where every leaf and every droplet of water is a potential threat to the mix.

All so that when Ari and Cynthia stand on that balcony and sing “Because I Knew You,” the voices you hear are what they gave you in the moment, not a clean, polished replica assembled later in an ADR booth.

There are two ways to spend money and effort in a musical:

• You can spend it on ADR and studio time, and accept the creative compromises that come with actors trying to reinhabit a moment they lived months earlier.

• Or you can spend it on VFX paint-out, quiet floors, Silent Wind, double-miking, extended balconies, and custom IEM’s to carry the original performance all the way to the screen.

On Wicked: For Good, we chose the second route.

The Keyboard, the Playback, and the Tears

Earlier, I talked about the way we wove live keyboard with playback across the film. On “For Good,” those decisions were laser-targeted to the emotional structure of the song.

I asked Ben Holder what he remembered about the breakdown, and his summary perfectly matches what we built:

• The beginning of “For Good” and the very end were largely driven by live keyboard. These are the sections where the tempo is most free, where the characters are searching for the words and the music follows their inner rhythm.

• The middle section, including the “And just to clear the air, I ask forgiveness” middle eight and the final big chorus, runs to playback. We were still recording everything live, with the full six-mic setup, but the backbone of the music was Greg’s track, locking the rhythm section in and allowing the song to expand in scale.

• After that last chorus, when the song drops back down into the softer “Because I knew you, I have been changed for good” alternation, we went back to live keyboard. The dynamic drops, the emotion peaks, and the accompaniment needed to be able to breathe with the actors as they cried and sang through those final lines.

That final section is burned into my memory from my position at the cart.

I have said before that when a performance is really happening, I am aware of my faders as an instrument. On those takes, when Ari and Cynthia were standing there with tears streaming down their faces, harmonising through the last “For Good,” it felt as if the whole crew were playing one piece of music together.

Ben was shaping the keyboard in real time to support their fragility. Josh was making sure there was no technical cliff edge when we changed from playback to live accompaniments. Arthur and Robin were holding those booms half an inch apart, breathing with the actors. Taz, the Art Department, Props, and SFX had created a world of leaves and puddles and wind that felt real but stayed quiet enough to let the song live. Costume had made sure the transmitters were exactly where they needed to be, and VFX had already signed up to remove whatever mics we had to place in shot. And I was sitting there, riding those six microphones as if they were one voice, making sure I did not clip, did not miss a head turn, did not allow a single crackle of leaf or splash of water to intrude at the wrong moment.

When people say “there was not a dry eye in the house,” it is normally hyperbole. On those days, on that balcony, it was simply true. I looked around after one of those takes and saw Grips, Sparks, Camera Assistants, everyone, just quietly wiping their faces.

That is why we do it live. That is why we build playback rigs that behave like an orchestra pit, and why we spend two days negotiating the exact placement of every leaf. Because when a performance like that happens, you only get one chance.

My job as a Production Sound Mixer is to be able to turn to Jon, to Cynthia, to Ari and say, with absolute honesty:

“I got it. It is all there. What you just did will live on that screen exactly as you gave it to us.”

On Wicked: For Good, and especially on “For Good,” I can say that. And I can also say we did it as one department—Sound & Music, the orchestra pit under the stage, playing in service of the story.