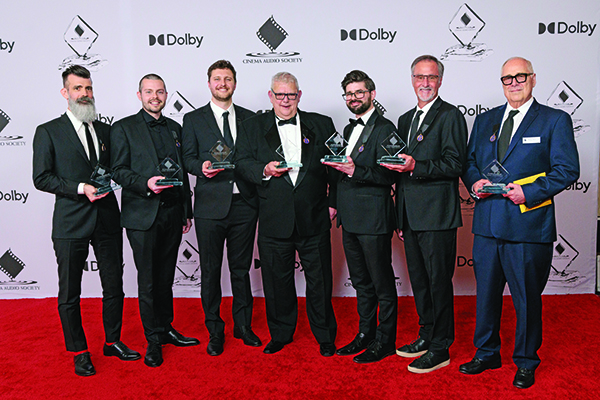

The awards for outstanding sound mixing in film went to:

MOTION PICTURES – LIVE-ACTION

A Complete Unknown

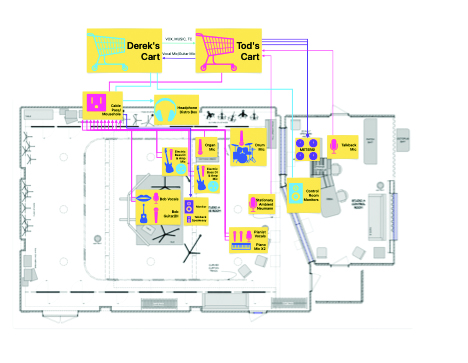

Production Sound Mixer – Tod A. Maitland CAS

Re-recording Mixer – Paul Massey CAS

Re-recording Mixer – David Giammarco CAS

Scoring Mixer – Nick Baxter

ADR Mixer – David Betancourt

Foley Mixer – Kevin Schultz

Additional Sound Team:

Jerry Yuen – Boom

Terence McCormack Maitland – Utility

Pro Tools Playback – Derek Pacuk

MOTION PICTURES – ANIMATED

The Wild Robot

Original Dialogue Mixer – Ken Gombos

Re-recording Mixer – Leff Lefferts

Re-recording Mixer – Gary A. Rizzo CAS

Scoring Mixer – Alan Meyerson CAS

Foley Mixer – Richard Duarte

MOTION PICTURES – DOCUMENTARY

Music by John Williams

Production Mixer – Noah Alexander

Re-recording Mixer – Christopher Barnett CAS

Re-recording Mixer – Roy Waldspurger

NON-THEATRICAL MOTION PICTURES or LIMITED SERIES

Masters of the Air: S01 E05 Part Five

Production Sound Mixer – Tim Fraser

Re-recording Mixer – Michael Minkler CAS

Re-recording Mixer – Duncan McRae

Re-recording Mixer – Shane Stoneback

Scoring Mixer – Thor Fienberg

ADR Mixer – Sean Moher

Foley Mixer – Randy K. Singer CAS

TELEVISION SERIES – ONE HOUR

Shōgun: S01 E05 “Broken to the Fist”

Production Sound Mixer – Michael Williamson CAS

Re-recording Mixer – Steve Pederson CAS

Re-recording Mixer – Greg P. Russell CAS

ADR Mixer – Takashi Akaku

Foley Mixer – Arno Stephanian CAS

Additional Sound Team: Don Brown – Boom Op

Darryl Marko – Boom Op

Jenna Gouchey – Sound Assistant

Rob Hanchar – 2nd Unit Mixer

Marin Mitchell – 2nd Unit Boom Op

Patou Lauwers – Unit Sound Assistant

TELEVISION SERIES – HALF HOUR

The Bear: S03 E03 “Doors”

Production Mixer – Scott D. Smith CAS

Re-recording Mixer – Steve “Major” Giammaria CAS

ADR Mixer – Patrick Christensen

ADR Mixer – Kendall Barron

Foley Mixer – Ryan Collison

Foley Mixer – Connor Nagy

Additional Sound Team: Joe Campbell – Boom Operator

Michael Capulli – Boom Operator, Nick Price – Utility

Eric LaCour – Utility, Sharon Frye – Utility, Uriah Brown – Sound Intern

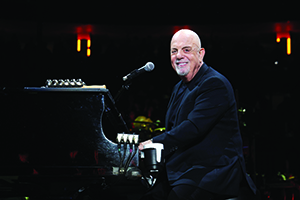

TELEVISION NON-FICTION, VARIETY or MUSIC – SERIES or SPECIALS

Beatles ’64

Re-recording Mixer – Josh Berger

Re-recording Mixer – Giles Marti

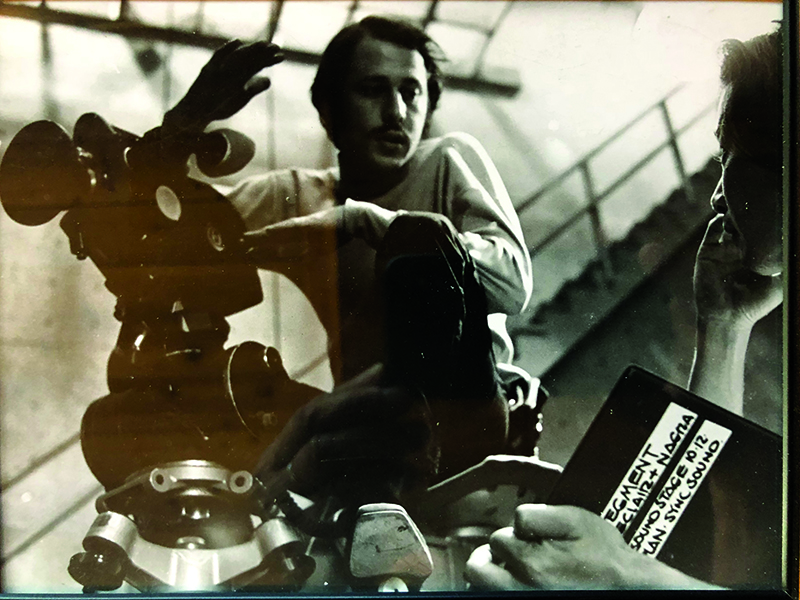

CAS FILMMAKER AWARD

Director Denis Villeneuve

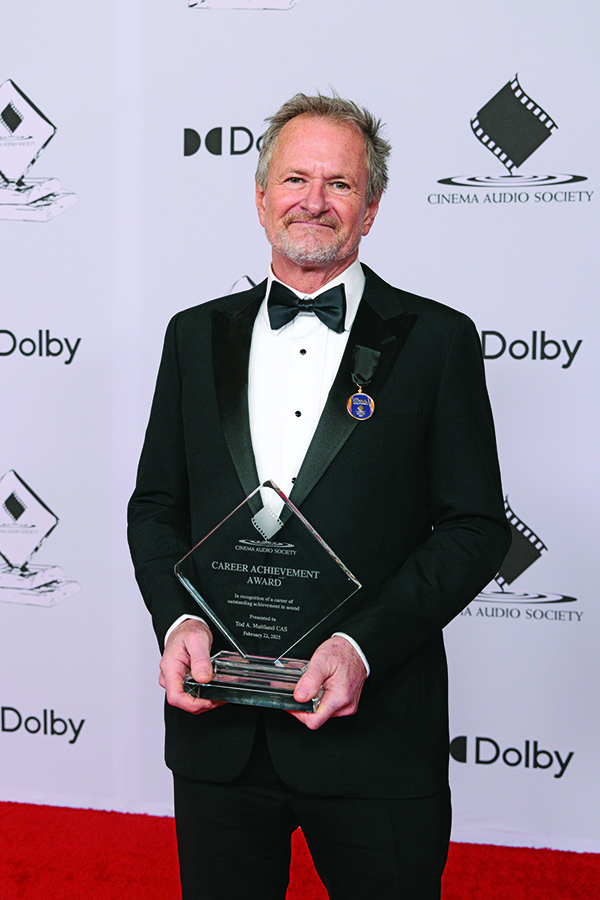

CAS CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD

Production Sound Mixer

Tod A. Maitland CAS

STUDENT RECOGNITION AWARD

Kat Frazier of Ohio University

Tejumoluwa Olarewaju

Savannah College of Art and Design

Guillermo Moya

Full Sail University

Aidan Jones

Savannah College of Art and Design

AMPS AWARDS

Dune: Part Two

Production Sound Mixer – Gareth John

Supervising Sound Editor – Richard King

Re-recording Mixer – Ron Bartlett

Re-recording Mixer – Doug Hemphill

Additional Sound Team:

Tom Harrison – Key 1st AS

Freya Clarke – 1st AS

Mátyás Tóth – 2nd AS

Jordan

Tarek Abu Asmar – 2nd AS

UAE

Jad El ASmar – 2nd AS

2nd Unit

Levente Udud – Sound Mixer

Balazs Varga – Technical Support

Fanny André – 1st AS

György Mihályi – 1st AS

L-R: Gareth John, Ron Bartlett

Photo: Kate Davis

BAFTA

Dune: Part Two

Production Sound Mixer – Gareth John

Supervising Sound Editor – Richard King

Re-recording Mixer – Ron Bartlett

Re-recording Mixer – Doug Hemphill

Photo: Dave Benett/BAFTA/Getty Images

OSCAR

Dune: Part Two

Production Sound Mixer – Gareth John

Supervising Sound Editor – Richard King

Re-recording Mixer – Ron Bartlett

Re-recording Mixer – Doug Hemphill

Gareth John, Richard King, and Ron Bartlett pose

backstage with the Oscar® for sound.

Photo: Etienne Laurent/The Academy/©A.M.P.A.S.