A Tribute to Stefan Kudelski and the Nagra Recorder

by Scott D. Smith, CAS

Long considered the “gold standard” for location sound, the Nagra recorders established a level of technical superiority and reliability that to this day is unmatched by almost any other audio recorder (with the possible exception of the Stellavox recorders, designed by former Nagra engineer Georges Quellet).

Long considered the “gold standard” for location sound, the Nagra recorders established a level of technical superiority and reliability that to this day is unmatched by almost any other audio recorder (with the possible exception of the Stellavox recorders, designed by former Nagra engineer Georges Quellet).

With the death of Stefan Kudelski in January of this year, this would seem an appropriate time to look at the history of the Nagra recorders and the man responsible for their huge success.

The Early Years

It should probably come as no surprise that Stefan Kudelski would be destined for great works. Born in Warsaw, Poland on February 27 of 1929 to Tadeusz and Ewa Kudelski, it would become clear to those around him early on that he possessed a level of intelligence and ambition exhibited by few other young men his age. His father had studied architecture at Lvov Polytechnics, but later went into chemical engineering. His mother was an anthropologist. Despite this, his childhood years were far from idyllic. With the imminent Nazi attack on Poland in September of 1939, at the tender age of 10, Kudelski and his family fled Warsaw, first to Romania, then to Hungary, and finally to France. He resumed his high school education at the Collège Florimont in Geneva, and later studied electrical engineering at the Ecole Polytechnique in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Like most successful endeavors, Kudelski did not originally come to the idea to create a portable tape recorder directly. His initial interest was sparked by the terribly inefficient work he saw being done at a machine shop in Geneva, where each piece was turned by hand. Realizing that much of this repeatable work could be done by automation, he set about designing what would have been one of the first CNC machine tools. However, he lacked a method to record and store the data necessary to control the motors, and began to look at magnetic recording as an possible medium for data storage.

After dismantling an old recorder to study its design, Kudelski then set about designing a new recorder from scratch. This recorder would be destined to become the Nagra I. However, as the son of a poor refugee family, he was unable to interest anyone in his CNC machine tool project, so he turned his focus to designing a recorder suitable for broadcast use.

Working from his apartment in Prilly, he managed to scrap together enough money to design a prototype machine. It was an instant success, and he sold his first machine for the sum of 1,000 CHF. (While this only amounted to about $228 USD in 1952, it was still a significant amount of money for the young Kudelski). This initial sale was followed by orders from both Radio Lausanne and Radio Geneva.

In May of 1952, on the heels of interest from some well-respected European reporters, he receives an order for six Nagra 1’s from Radio Luxembourg, which convinced Kudelski that he is on the right path. It was at this time that Kudelski left the Ecole Polytechnique and pursued development of the Nagra full time. (Years later, he would receive an “honoris causa” degree from the Ecole Polytechnique, in recognition of his work in developing the Nagra recorder.)

By the end of 1953, Kudelski had established manufacturing operations at a house in Prilly (west of Lausanne), and employed a staff of 11. Toward the end of 1954, improvements were made to the machine (now called the Nagra II), with printed circuit boards being implemented for the audio electronics. The orders continue to roll in, virtually all from word-of-mouth, and by the end of 1956, the staff numbers 17. Despite this success, Kudelski recognizes that there are still improvements that need to be made, especially in the area of the drive mechanism. He continues development of the machine, but opts for a ground-up redesign, as opposed the incremental changes between the Nagra I and II. The result is the Nagra III, introduced in 1958.

The Nagra III Makes Its Debut

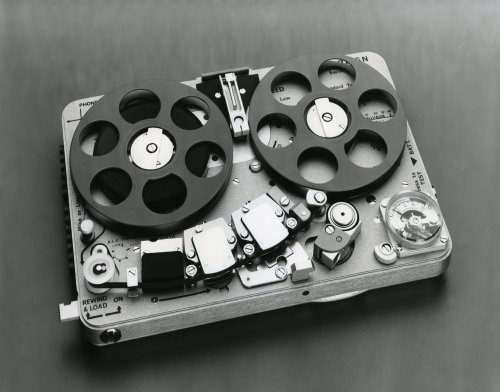

The design of the Nagra III marked a significant departure from the Nagra II. Gone was the spring-wound drive mechanism, replaced by an extremely sophisticated servo-drive DC motor. Also absent was the tube-based amplifier circuitry. In its place was a series of modules, each encased in metal, which contain the individual components of the machine. It also sported a peak reading meter (the “Modulometer”), which set it apart from most of the other recording equipment of the period, which still relied on VU meters. It was designed for rugged operation conditions, and could be powered from 12 standard “D” cell batteries.

Acceptance of the Nagra III was almost instantaneous. 240 machines were built in 1958, and in 1959, the Italian radio network RAI (Radio Audizioni Italiane) ordered 100 machines to cover the Olympic Games in Rome, paying cash in advance. With this rapid expansion, larger premises are acquired in Paudex (near Lausanne). Since the Nagra III relied heavily on custom machined parts, a significant investment in machine tooling, along with skilled machinists to run them, was required to keep pace with orders that were now coming in from networks around the world, including the BBC, ABC, CBS, NBC and others. By 1960, there were more than 50 employees working in Switzerland, and a network of worldwide sales agents was established to support the sale and service of the machines.

Acceptance of the Nagra III was almost instantaneous. 240 machines were built in 1958, and in 1959, the Italian radio network RAI (Radio Audizioni Italiane) ordered 100 machines to cover the Olympic Games in Rome, paying cash in advance. With this rapid expansion, larger premises are acquired in Paudex (near Lausanne). Since the Nagra III relied heavily on custom machined parts, a significant investment in machine tooling, along with skilled machinists to run them, was required to keep pace with orders that were now coming in from networks around the world, including the BBC, ABC, CBS, NBC and others. By 1960, there were more than 50 employees working in Switzerland, and a network of worldwide sales agents was established to support the sale and service of the machines.

Nagra Enters the Film Business

The application of portable sound recording to the film industry was not lost on Kudelski or his agents. In 1959, French director Marcel Camus used a Nagra II to record part of the sound on the feature production of Black Orpheus, shot on location in Brazil. Sensing that this could be a burgeoning market, Kudelski quickly set about designing a version of the Nagra III that could utilize a pilot system for synchronous filming (referred to as the PILOTTON system).

This early version of this system was based on technology initially developed in 1952 by Telefunken and German Television, which consisted of a single center channel pilot track about .5 mm wide. However, it did not have HF bias applied to it, which caused the distortion to be rather high, and bled into the audio track. Realizing that a better solution was needed, Kudelski invented the Neopilot system to replace the PILOTTON system. This design consisted of two narrow tracks, recorded out of phase with each other, which resulted in the signal being cancelled out when reproduced by a full-track head. The addition of HF bias helped reduce distortion, which resulted in minimal interference to the program audio.

A companion synchronizer (the SLP) was developed at about the same time, which provided a method to resolve synchronous recordings on the Nagra III. The design of the DC servo motor system provided for an elegant approach to this task, making the AC motor drive systems of the day look archaic in comparison.

The first of the Nagra III’s equipped with the new Neopilot system were delivered in 1962, resulting in a huge increase in sales. Lead times for the Nagra III now grew to 6–8 months, requiring yet more space for production. Also, there were restrictions placed on business by the Swiss government in regards to how many workers could be hired, which hampered the growth of the company.

In 1964, additional office and production space is rented in Renens, with further premises acquired in 1965 in Malley. By the end of 1965, the decision was made to purchase a factory in Neuchâtel. Finally, a huge tract of land is purchased in Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, which allowed for the construction of a dedicated factory.

Nagra IV Debuts

By 1967, the sale of the 10,000th Nagra III is celebrated, and in 1969, the company moves into their new facilities in Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne. 1969 also brought the introduction of the Nagra IV recorder, which marked yet another significant improvement in analog recording technology. While the basic transport design mimicked that of the Nagra III, the new machine now used much more reliable silicon transistors and sported two mike inputs. The pilot system was also improved, with the flux level on tape being standardized, regardless of the voltage present at the pilot input. The signal was also filtered which significantly reduced the amount of noise that could bleed through into the audio track. Approximately 2,510 of the new machines were built in 1969.

Not content to leave well enough alone, one year later, Kudelski introduces the Nagra 4.2L recorder. While the 4.2L offered a few improvements over the IV, they were not as significant as the changes seen between the model III and IV. If some industry observers were of the opinion that Kudelski had begun to slow down further development of analog recorders, they were significantly underestimating his ambitions…

If One Channel Is Good, Why Not Two?

Seeing further opportunities in the sale of machines to the broadcast and film markets, in 1971 Kudelski introduces a stereo version of the Nagra 4.2, called the IV-S. Built on the same platform as the 4.2, the machines offered many of the same features, but with two channels of recording in the same footprint as the mono recorder. It also marks the introduction of a new pilot system, called NagraSync FM, which records a FM modulated pilot signal at 13.5 kHz between the two audio tracks. This allows for synchronous recordings, without having to reduce the width of audio tracks, and neatly solves the problem faced by trying to use the older Neopilot system for twochannel recording. It also allows for a limited bandwidth commentary track to be recorded on the same channel, which aids in slating for production situations where a standard “clapper” slate can’t be used, without interfering with the program being recorded. While stereo recorders were certainly nothing new at this point, all the commercially available machines were bulky AC–operated recorders, giving Kudelski yet another significant entry into the audio recorder market.

1971 also saw the introduction of the unique SNN recorder, a miniature recording using 1/8” wide tape, but in a reel-to-reel configuration as opposed to a cassette. Like its predecessors, it also had the ability to do synchronous recording. Although Kudelski had begun development work on the SNN about a decade earlier, he waited until 1971 to bring it to market. This year would also mark the introduction of equipment destined for applications outside of the traditional film and broadcast arena.

Diversification

Whether driven by the need to invent or recognizing that the market for portable audio recorders would eventually become saturated, it was about this time that Kudelski begins to design and manufacture equipment destined for applications outside of the traditional film broadcast market. While he had designed a recorder for military applications as early as 1967 (called “Crevette”), 1971 would mark a significant departure in the direction of the company.

Fresh off the heels of the Nagra SNN and IV-S recorders, in 1972 Kudelski introduced the Nagra IV-SJ, a two channel instrumentation recorder aimed at scientific and industrial markets. Recognizing the application of the SNN recorder for law enforcement use, Kudelski also introduced the SNS, which was a half-track version of the SNN recorder. Recognizing the need for a more economical ¼” mono recorder for broadcast, in 1974 Kudelski introduced the Nagra IS, originally designed to be a single-speed mono recorder aimed at reporters. With a footprint and weight that was almost half that of the 4-Series recorders, this machine gained rapid acceptance by broadcasters who were looking for a high-quality, economical recorder. Like other Nagra products, variations of the basic recorder were soon to appear, which could provide Neopilot sync for film use, as well as two-speed operation. Two year later, the Nagra E was introduced, which was a further simplification of the IS recorder.

Despite the simplification of these products, both maintained the unique trademark characteristics of Kudelski’s design approach, and would never be mistaken for some mass-market cassette recorder.

Just the FAX Ma’am

While Kudelski was known worldwide for his unique audio design talents, somewhat less well known was his keen interest as both a sailor and aviation buff. In fact, Kudelski established “Air Nagra” in the 1960s, which operated a few Cessna twin-engine planes, used primarily to transport businessmen in the local area. Ever aware of the opportunity to bring a new product to market, in 1977 Kudelski would introduce the “NAGRAFAX,” a unique portable weather facsimile machine aimed at the maritime market. While the military had a similar system in use, the NAGRAFAX was aimed at the commercial and private yacht market, and also saw use in airports, ski resorts and coast guard stations. This product would mark Kudelski’s first departure from recording equipment.

1977 saw the introduction of yet another instrumentation recorder, the Nagra TI, which offered four channels of recording (as opposed to the two channels of the Nagra IV-SJ). It also boasted a unique dualcapstan transport, which minimized disturbances in the tape path, a critical design component when the recorders were employed in military operations. This transport would become the basis for the Nagra TA recorder introduced in 1981. Essentially, a two-channel analog version of the TI recorder, the Nagra TA had the unique ability to chase timecode in forward and reverse, and was specifically aimed at the telecine post market.

While the T Audio recorder boasted the most sophisticated transport design of any of the Nagra analog audio recorders, its complex logic circuits caused many users to shy away from it, except for telecine applications, where it had no rival. Despite this, it is still highly prized among audiophiles for its stellar tape-handling features.

Nagra and Ampex—Strange Bedfellows

The year 1983 would see an unlikely alliance take place, with Nagra and Ampex embarking on a joint venture to introduce a portable 1” Type-C video recorder aimed at the broadcast market. While Sony already had a small 1” video recorder on the market, in predicable fashion, the design efforts of Kudelski raised the bar significantly. Employing a lightweight transport and surface mount devices, the new recorder (dubbed the VPR-5) brought a level of sophistication to the broadcast video recorder market that has never been seen since. While the VPR-5 enjoyed a brief period of popularity (with 100 machines ordered for use at the 1986 Mexico World Cup), the everchanging “format wars” brought a premature end to its use.

Nagra and the Cold War

In yet another somewhat unlikely alliance, soon after the introduction of the VPR-5, Nagra joined with the Honeywell Corporation with the intent to produce a highly specialized recorder designed expressly for military use. However, this venture, which utilized all of Nagra’s R&D operations, never brought a product to market. The project was quickly abandoned after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The only remnant of the effort is a prototype recorder called the “RTU.” This would be the last project that Stefan Kudelski would be engaged with directly in an engineering capacity.

Despite this misstep, much was learned during the development of the RTU, and in 1992 Nagra introduced the Nagra D, a unique (and proprietary) four-channel digital recorder aimed at the film and music recording market. While the Nagra D gained some adherents, by this time Nagra had unfortunately begun to lose its dominance in film sound to DAT technology, which had begun to make inroads in the market while they were still distracted by the Honeywell venture. (In fact, Nagra never did produce a DAT recorder, moving directly from the Nagra D open-reel digital recorder to the introduction of the ARES-C tapeless digital recorder in 1995.)

Despite losing some market share in traditional film sound recording to new players, Kudelski continues to design and innovate. In 1997, they introduced a line of high-end audiophile components, starting with the PL-P vacuum tube preamplifier, and later incorporating the VPA mono-block tube power amplifier, as well as the MPA 250-watt MOSFET power amplifier.

Even further afield from the original focus of the company was establishment of a division devoted to pay-TV set-top boxes for CANAL+ in 1989. This would turn into a very successful growth operation for the company, and continues to be the main business of the firm.

Nagra Today

In 2002, Nagra introduced the Nagra V hard drive recorder, which was intended as the replacement for the Nagra 4 series analog recorders. However, despite the excellent design, by this time Nagra had some of its footing in the film recording market, overshadowed by the development of DAT recording in the 1980s, and the introduction of the Deva hard drive recorder in 1997. Nonetheless, Nagra still enjoys a significant share of the broadcast journalism market with products such as the ARES series solid-state recorders. Currently operated as a separate entity located in Romanel under the moniker of Audio Technology Switzerland, the firm continues to pursue the film recording market, with the introduction of the Nagra VI hard drive/CF card recorder in 2008. Stefan Kudelski’s son, André Kudelski, continues as CEO and Chairman of the firm.

Despite the changes in technology that have taken place in the intervening years since the introduction of the first Nagra recorder, every sound mixer “of a certain age” I’ve spoken with can still recall the first time they used a Nagra recorder. Likewise, the stylistic contributions made to the film business by Kudelski’s introduction of the Nagra are immeasurable. Films such as D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back would have simply been impossible to do without the aid of lightweight cameras and recorders. The entire French New Wave movement, led by directors such as Francois Truffaut and Jean Luc Godard would arguably not even have existed without the aid of the Nagra recorder and Éclair camera. Thank you Mr. Kudelski for your marvelous invention.

The author wishes to thank Omar Milano for generously sharing the transcript of an interview he conducted with Mr. Kudelski. I am also grateful for the opportunity to have accepted the Wings Award on behalf of Mr. Kudelski at the Polish Film Festival in America in 2008. It was an honor.

© 2013 Scott D. Smith, CAS

Editors: We will present other articles in coming issues to explore the accomplishments of Stefan Kudelski. We invite members to submit stories and anecdotes of their experiences with the man and his recorders. Please send your anecdotes to: nagra@local695.com