by Julian Howarth & Tony Johnson

Julian Howarth

Seven years in the making, across two continents and with sound departments in the United States and New Zealand, this film was one huge undertaking for everyone involved. I headed up the set in the U.S. and Production Sound Mixer Tony Johnson (TJ) covered all things in New Zealand.

Ideas, methodology, equipment and a lot of sweat were shared throughout this process. I have asked that TJ join me in the writing of this as we have shared everything else during our time on this film, so why not? We filmed both The Way of Water and Fire and Ash during this time.

The plan was for all performance capture to take place in the U.S., at Manhattan Beach Studios, and then, once completed, the film would move to NZ to add the live-action components. In theory, the two would then combine seamlessly on screen.

Most scenes involving a human component were filmed twice, once on the Perf Cap Stage in the Manhattan Beach Studios, and then again on the live-action set built on The Stone Street Studios Wellington, New Zealand. Digital and physical sets had to match in scale and how they were lit. The human actors had to interact with Na’vi that were digitally rendered into the camera as a live image. Ryan Champney, our Virtual Production Supervisor, oversaw this process with elegance and command. His assistance and knowledge guided my every move throughout filming.

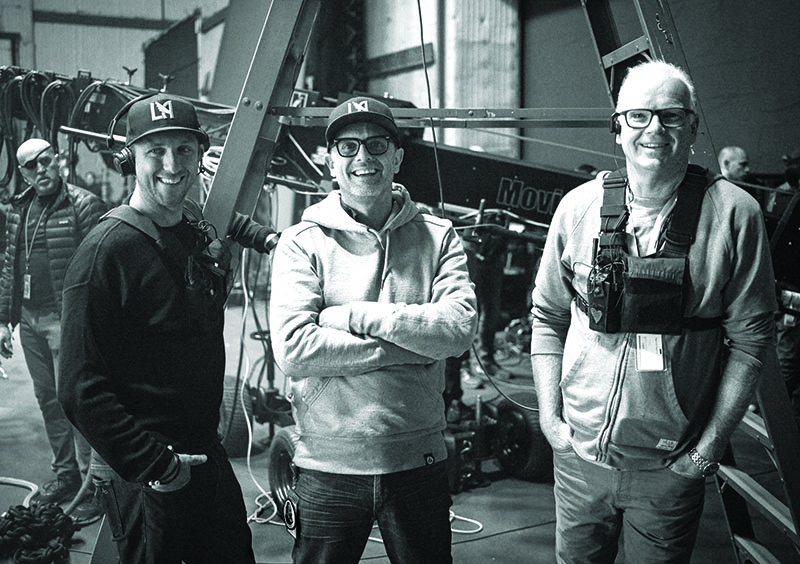

None of what I will describe would have been possible without my team. Ben Greaves’ (1st AS) contribution cannot be overstated. His problem solving, work ethic, and attention to detail made this entire collaboration possible. He has worked alongside me for so long now, we have a shorthand and way to work. He is my closest friend and ally.

We had many other team members, Kayla Croft, Scott Solan, Yohannes Skoda, Zach Wrobel, Tim Salmon, Jamie Gambell and Iris Von Hase, playing parts in utility, additional boom and comms. All of them brought their A-game and again without them we would not have been able to navigate this herculean task.

(L-R) Oona Chaplin, Devereaux Chumrau, Alicia Vela Bailey, Courtney Chen, Kevin Henderson, Jamie Landau, and Kevin Dorman

As a Production Sound Mixer, I understand that sound is not merely an addition to the visual experience—it’s a critical component that can transform a simple scene into a captivating narrative. The production of Avatar: Fire and Ash exemplified this. Throughout the filming process, our team implemented various techniques to ensure that every auditory element complemented the film’s immersive experience on set, as well as in the final product. In the world of filmmaking, production sound plays an instrumental role in crafting the final product, often going unnoticed by audiences but essential for fully engaging them in a story. The philosophy was simple: capture truth in the moment. Not just dialog, but the emotion behind it. Not just sound, but story.

This was a theatrical experience on a performance capture stage.

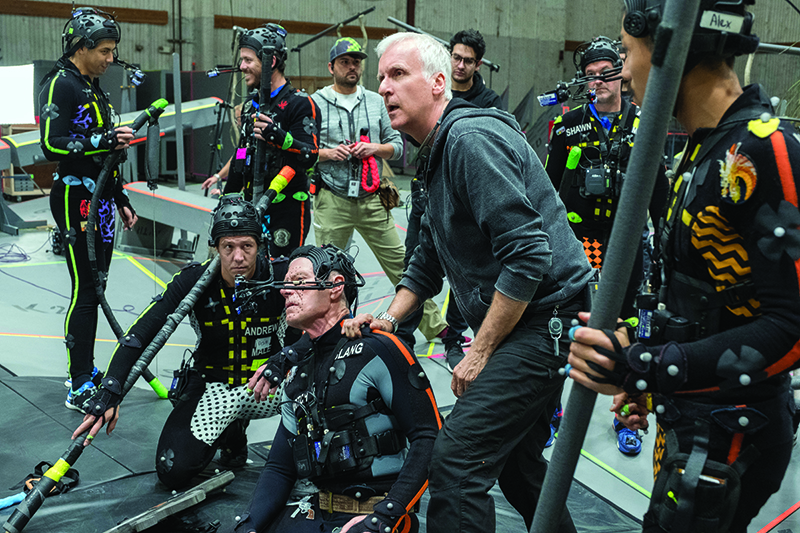

When filming on a performance capture stage, multiple cast members and background actors inhabit the same space, often interacting in complex ways. Capturing sound becomes a delicate balancing act of technology and artistry. From the outset, I knew this was going to be a unique experience—bigger, deeper, and more demanding than anything I’d ever worked on.

Jim wanted every breath, every reaction, every word—improvised or scripted—captured in real time. The scale of the sound team’s responsibility reshaped my understanding of what production sound could be. Each scene was played and directed like in theater, everyone talked. With the versatility of performance capture and the nature of Jim’s direction, it could be everyone’s close-up during one single take.

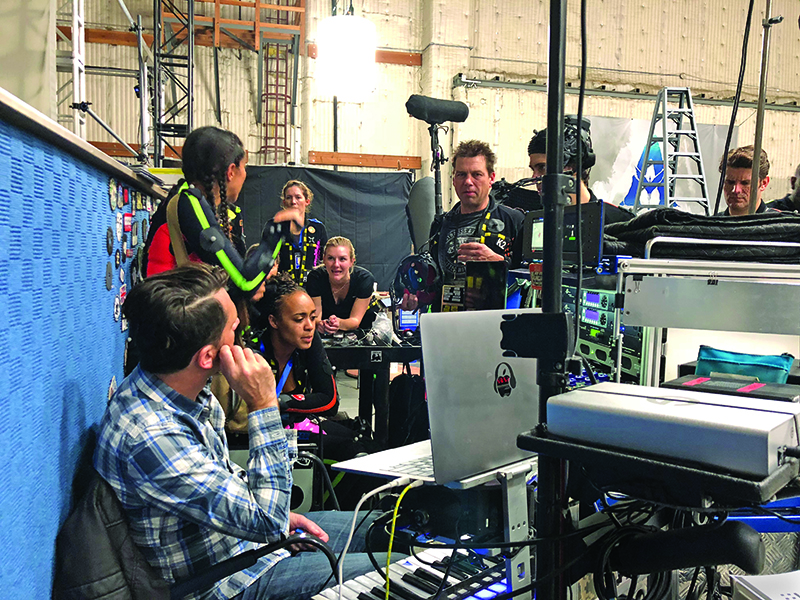

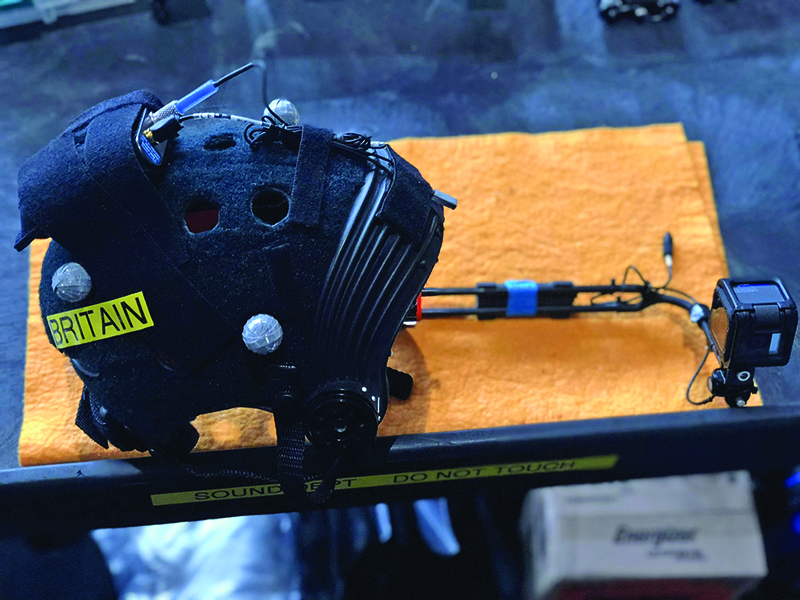

Every actor wore a helmet that holds the face camera, and we affixed DPA 4071 microphones onto each helmet. We used around fifty in total, and rigged every helmet beforehand. The mics were placed on the camera arm to the side of the mouth ensuring the elimination of any plosives that could affect the resulting performance and a corresponding transmitter connected at the offset. I was using Lectrosonics transmitters but swiftly changed to the Astral system as the NEXUS control protocol made changes simple and quick. The range of dynamics in the performances demanded versatility and the simplicity of gain structure that the Astral system gave us, its 32-bit float system made this possible with little or no interruption to the actors on stage. Every time an actor entered the Performance Capture Stage, we assigned a TX and changed metadata to correspond to their track. Editorial had to cope with an extraordinary number of tracks, and they needed this metadata to be exact and precise. With twenty actors in any scene at a time, we had one mix track for editorial purposes, two booms and then twenty ISO’s relating to each actor. The final twenty-fourth track was used as reference for any playback (music or FX) we had.

On average, we had around fourteen witness cameras that filmed every nuance and expression so that Jim could review immediately after each take. Video playback was undertaken by Shahrouz Nooshinfar and Dan Moore who I provided with mix tracks to go alongside the video matrix they created for Jim to review. All our systems, virtual and live, had to sync up with each other. We spent at least thirty minutes at the start of each day running sync tests to ensure that happened.

Ambient FX and musical cues were piped in live, either through stage speakers or personal earpieces. Actors heard the world they were meant to inhabit, and their responses became more visceral. With Assistant Editor Ben Murphy, I developed real-time soundscapes played through Pro Tools, running on a MacBook Pro and Focusrite 4i4 interface. Audio throughout was via Dante to the main cart.

It wasn’t just noise, it was narrative. Such effects help actors react instinctively, allowing their performances versatility and reactive to a world enhanced by our playback. For instance, the sound of a menacing helicopter hovering overhead can shift the energy of a scene, enabling actors to channel the environment into their portrayals organically.

For specific cues, like a sudden explosion, beeps from machines, breeching Tulkun, gunfire, etc., I used Ableton Live to trigger these effects. The use of live sound effects on set further enhanced the performance quality and gave real-time reactions to real-time sonic events; much better than an AD shouting BANG!

Jim was always five steps ahead and to keep up we had to be prepared for everything at any time. Playback, earpieces, rapid cast, and environment changes. We are there to service Jim’s vision, and we could never rest on our laurels thinking we had the day covered. Something new and challenging would always present itself and we had to be ready to meet those challenges. We had to stay sharp, prepared for anything. There could be no second chances. Sound had to be clean, immediate, and seamless.

Beyond dialog, we recorded entire musical sequences: tribal songs, dances, ceremonial drums all performed live. These were captured with help from Simon Franglen, Composer and Dick Bernstein, Music Editor. Earpiece playback ensured clean vocal takes. Performers like Zoe Saldaña, Kate Winslet, and Oona Chaplin delivered haunting, powerful renditions. It was honest and raw. While recording to my Cantar, audio was sent via Dante to the Pro Tools rig to record side by side.

When we moved into the water work, things got really interesting. We had two tanks: one small, circular one for singular performances and testing, and the main stage tank, which was 90x40x20 ft (27.4x12x6 m), holding around nine hundred thousand gallons of water. It was so big that operations had to be conducted from a flight deck at the surface and a bridge that would span the sides. The water environments were dynamic—wave machines, adjustable floors, even a water turbine system that could simulate a river with current up to five knots. It could be a beach, a swamp, a river, the reef shallows, the back of a Tulkun or out in the deep ocean. Anything Jim could dream up.

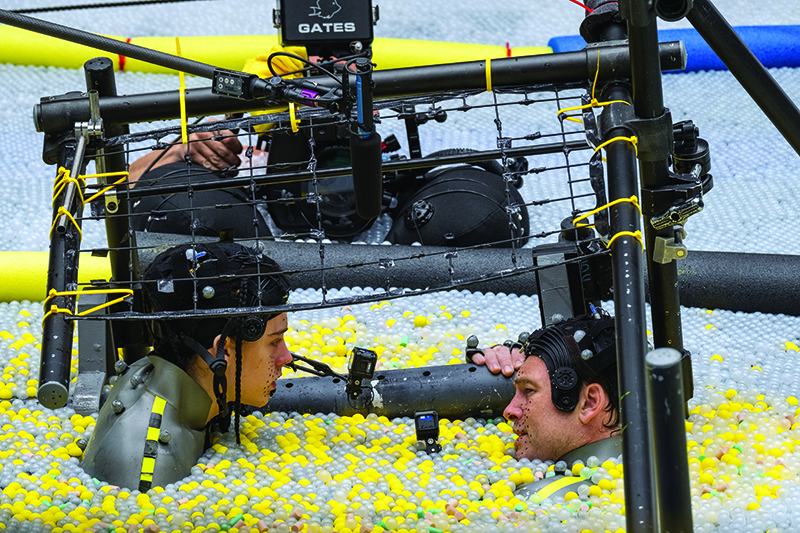

Performance capture in water is an entirely different science. Reflective surfaces disrupt optical tracking and bubbles confuse capture cameras. The solution? Thousands of translucent plastic balls to break the water surface while allowing light through. The problem was they made a LOT of noise. How would we solve this? We always have a couple of boom mics near the surface but as with the stage volume, and the nature of the performances, we really needed a mic on each helmet. Signal-to-noise ratios would always determine what the best method was.

We mounted Lectrosonics WM transmitters on the helmets, with antennas carefully positioned above the waterline. Even at shallow submersion, water kills RF signal, so mic and transmitter placement became a fine art. For underwater action with no dialog, we used an Ambient Soundfish ASF-1 Hydrophone which captured sound effects but also used it to monitor the underwater comms too. If there was ever an issue with the comms, we would know immediately and could fix it.

The real challenge is depth. At thirty feet, even waterproof lavaliers buckle under pressure. The diaphragm collapses, just like a human eardrum. We couldn’t risk losing the moment when a character bursts to the surface, gasping, those moments carry the emotional core of a scene.

We innovated adding a secondary diaphragm, a latex membrane to absorb pressure and shield the capsule. Placement had to be perfect to prevent turning the helmet microphonic, so Ben constantly made small modifications to ensure everything worked as we needed. The Lectrosonics WM transmitters were also tested to their limits in terms of the depth they were taken to and the punishment they endured. They performed way beyond the limits of what they were designed for.

For delicate surface scenes, ADR was off the table. Jim was adamant. “We’re using production sound.” The plastic balls were too noisy. I spent quite some time trying to find a solution to this issue, and it came to me from my son, who was playing with his NERF gun at the time. The projectiles were foam balls. When one hit me in the head, I had my Eureka moment, they were soft, silent, and exactly the right size. I decided to take them to work to test out. They degraded quickly in chlorinated water, so we decided to only use them for specific and intimate moments. It took time to set up when we used them but the difference in dialog quality was everything. I was in constant contact with Gwen Whittle, Supervising Sound Editor, throughout the whole process, and she did incredible work cleaning up what we recorded, and you hear the results in the film.

We also developed waterproof mic cases for live underwater recording—depth proof and timecode stamped. Live-action diving masks allowed us to hard line to the surface or record onboard. After each take, we’d swap the packs, off-load the SD cards, and send audio directly to editorial. The whole process, from water to QTAKE to Avid, took under two minutes. It was tight, intense coordination across departments. Everyone knew what needed to happen; everyone delivered.

Sound and communications on the tank served many purposes. We had speakers surrounding the tank, including underwater and floating units. Jim could speak directly to actors in real time so that he could give notes and adjust moods. During the tank work, Jim would wear a PTT mic. The speaker system served as VOG for instructions, but also as a means of playback for music and atmos. We used immersive audio environments to set scenes: swamp ambiences, open ocean. We played music cues for festivals or underwater dances. Simon and Dick were, again, there with us, ready to adapt to anything Jim wanted. All playback was controlled through our Pro Tools rig.

The comms system was also piggybacked to our dive supervision and safety team. They had to perform countdowns for breath holds, communications to underwater rigging and safety teams and should the situation arise (which it didn’t, thank goodness), coordinate rescue procedures.

The Avatar family was our fortress. It protected us, uplifted us, and challenged us to go further than we thought possible. The scale was massive. The expectations even bigger. Working on Avatar felt less like making a film and more like building a world with a family. To make something of this scale work, you have to be completely integrated with other departments: Editorial, Virtual Production, Video Playback, Environment Design, Production Design, Motion Builder (the system that controls all virtual aspects), Props, Costumes, and more. We relied on each other constantly, syncing our efforts to bring Jim’s vision to life. That kind of collaboration creates bonds that go deeper than the usual set relationships. It becomes something personal, every team member worked tirelessly to support each other at work and at home.

The family attitude is what made this film, cast, and crew alike. Over the years, I watched the younger cast grow into remarkable adults. We shared birthdays, breakthroughs, and plenty of long, exhausting days. I grew to love this Avatar family of mine.

Producer Jon Landau embodied this spirit. He was always there, listening, encouraging, and setting the tone. He made the big machine human. I’ll never forget when filming had paused during the pandemic in the U.S., and everyone was scattered, I got a call. “Julian, it’s Jon. Are you okay? How’s your family? Do you need anything?” He didn’t have to call but he did. That’s who he was. A leader not just with vision, but with heart. Jon passed away in July 2024. I miss him dearly, but in every frame, I still feel his presence.

John Refoua and David Brenner, two brilliant Editors, passed during this journey. They shaped the world of Pandora in more ways than most people will ever know. They were artists. They were friends.

Finally, what stays with me is the people.Their integrity, their spirit, their belief in the story we were telling. And that, in the end, is what sound really captures—not just what was said, but what was felt.

Tony Johnson

As Julian was completing the performance capture work in Los Angeles in 2019, I flew over to pick his brain and establish what I needed to prep for the live-action shoot in New Zealand.

They were filming tests on Spider (Jack Champion) in Manhattan Beach, and it was a good time to get a sign-off on the placement of Spider’s lavalier mic. Spider was bare-chested for the entire shoot, so the dreadlocked wig was the only place suitable. We had costume and hair help make a space for the Zaxcom ZMT3 in the back of the wig which was hidden by the dreadlocks. We then threaded a DPA 6061 through a dreadlock at the side of his head and that never changed for the entire shoot. It was a great win and the hair helped as a wind cover as well.

When we filmed the human actors on Pandora, they all wore oxygen masks with prop oxygen packs on their waists. There was a tube connecting to the mask so with Jim’s blessing, we would thread a lav up through the tube and bring it out through the rubber shroud around the mask, it was seen on camera. However, the glass lens of the mask was going to be added in VFX later, so it was easy to paint out the lav too. The Zaxcom ZMT4 transmitters went into the oxygen packs which were hollowed out for our benefit and were just big enough to house the TX. I could also get Zaxnet reception through the pack, which was great as I had full gain control from my desk.

This became a go-to as we had thirty lavs wired into oxygen masks for the duration. It was then easy to just plug a TX in and go. Katie Paterson was 2nd AS and she was in charge of managing this process, working with Prop Mask Head Richard Thurston. It was an ongoing upgrade to when we started in 2019; then we were using ZMT3’s and a mixture of B6 and DPA 6061’s. From 2022 on, we went to ZMT4’s and all DPA 6061’s. Funny to have a job last so long that technology upgrades with you on the way.

After the first Avatar, Jim wanted a better way for having accurate eyelines between humans and Na’vi characters in the same scene, something other than the tennis ball on a pole method. It needed to be a way where the Na’vi and humans could walk and talk, and move around, while maintaining an accurate eyeline, remembering the Na’vi are more than nine feet tall.

What came next was an ingenious eyeline system comprising of a four-axis cable cam with a wire tower and motor on four corners of the set. Where a camera would traditionally be mounted, instead, we had a tablet for the image of the Na’vi character, and a small battery-powered Bose speaker and a Lectrosonics LR receiver. Editorial would make up the clip of a character from performance capture, such as Stephen Lang’s Quaritch, that Julian had recorded, and was transmitted to the tablet. The sound was routed through my desk and transmitted to the LR and speaker. Jim did not want earwigs as he wanted the dialog to come from the same place as the characters’ image. I mixed the playback and live-action dialog while the actors would look at the image of Quaritch on the tablet. The cable cam movement would allow the actors to see Quaritch as he walked and interact with him all at the correct height. The cable cam had electric motors on the four bases and fortunately, the noise was something post could remove. The Bose speaker was perfect as it projected the sound in an omnidirectional way which meant the actors could hear the dialog from anywhere on the set.

The audio clips included breaths and effort as well, as the dialog. This would often clash with the live-action dialog, so I had to drop it out. This meant I had to have the playback track routed to the right-hand side of my headphones, pre-fader so I could know when to fade the extraneous sounds out. I had to trust that I had the lavs, booms, and any external issues sorted before we shot, as my monitoring was compromised. A big shout-out to my 1st AS, Corrin Ellingford, who did every shoot day with me over a five-year period on A2 and 3. His contribution was immense.

My crew setup for Avatar was like no other. We realized early on we could not have a traditional four-person crew because we only used one Boom Operator on most setups. I needed a 1st AS beside Jim Cameron and Maria Battle-Cambell, our 1st AD all the time, for the flow of information and any last-minute changes. The sets were huge, and I was a long way away from the action.

Sam Spicer was our main Boom Operator, and on one very memorable occasion, he arranged for a cherry picker to take him out over the Matador boat on a giant motion base to get the boom right over Scoresby’s head for the pivotal scene. Scoresby was dowsed in water seconds before we went for a take which consisted of a bucket of water being tipped over him. This rendered the lavs useless and with the pressure of the situation and what was at stake to get the shot, this moment stayed with me and reinforced my ethic of teamwork and never giving up!

A huge thanks to the New Zealand sound crew: 1st AS Corrin Ellingford, 2nd AS Katie Paterson, Boom Operator Sam Spicer, and Sound Interns Benny Jennings and Hayden Washington Smith. Second Unit was handled by Mixers Chris Hiles and Steve Harris. We had up to six people in our department on any given day.

For the live-action underwater shoot, we took Julian’s lead from his underwater experience, and used Countryman B3’s inside the masks. We had Ocean Technology Hi Use connectors for all underwater audio cabling and it was 100% reliable. We also used Julian’s method of putting latex over the capsule even though it was in a mask as the pressure at five meters (sixteen feet) down would be too much otherwise.

One of my most memorable experiences on Avatar was when we had Jemaine Clement’s (Garvin) underwater having a conversation with Scoresby, who we had shot previously on the ship. The original idea was someone would read the off-camera lines through a VOG to the underwater speaker. At the last minute, Jim wanted to use Scoresby’s dialog from the scene he had in the Avid on set. I was given the file minutes before a take to download to the Ableton, so I could have each line on a separate key and play them on Jim’s cue underwater to Garvin. The idea of playing dialog from a keyboard to an underwater speaker so Jemaine could perform the scene five meters below surface, reminded me of how cool my job is.

On Saturday, July 6, 2024, while the crew was prepping the Motion Base shoot, the mood turned very heavy as we were called into a huddle where it was announced that Jon Landau had passed. We knew he was unwell, but the outpouring of grief and emotion was all laid bare. We had lost our guide, the man everyone loved. Jon was an incredible person and leader for the Avatar family, and it was acutely felt in Wellington, New Zealand, where he spent so much time. Jon was known widely around the city as he became a big part of the community.

During the pandemic, with all of the local food truck holders in the city out of work, Jon employed them to provide our second meal at the studios. They would have several hundred hungry crew to feed and stay in business, just one of the many things he did here in NZ that will always be remembered.