by Scott D. Smith CAS

The challenges of managing kitchen chaos

Back in 2021, I received a call from a Unit Manager whom I had previously worked with, inquiring if I wanted to do a pilot for a little FX show that was based on running a take-out sandwich shop. “Sure,” I said, without really thinking of what might be waiting for us. I had done other shows which involved restaurant and kitchen sets. I mean, how difficult could it be? Little did I imagine what it would morph into four seasons of a top-rated TV show that would go on to win multiple Emmy awards for the cast and crew, along with some highly unusual challenges presented to the production sound crew.

Back row L-R: Michael Capulli (Boom), Nick Ray Harris (Mixer), Nicholas Price (Utility), Joe Campbell (Boom), Uriah Brown (Utility). Front row L-R: Katie Campos (Playback), Sharon Frye (Utility), Scott D. Smith (Mixer)

The Show

The Bear began life as a fast–paced family drama revolving around the travails of running a Chicago-based sandwich shop, which had come into the possession of a pair of cousins (played by Jeremy Allen White and Ebon Moss-Bachrach). It was immediately clear these two characters did not see eye-to-eye when it came to running a restaurant, resulting in frequent clashes, involving shouting matches, kitchenware getting tossed around, and general mayhem. Right away that meant we couldn’t use our usual approach to recording dramatic dialog. Overlapping dialog, kitchen chaos, and a dynamic range that would go from a whisper to shouting within a single shot were going to be the norm. Oh, and multiple cameras, with few rehearsals…

The Set

The kitchen set used for the pilot was an actual restaurant kitchen that had been shuttered, located in a commercial building on the north side of Chicago. Since we were free from the constraints of an operating kitchen, we were mostly able to control the noise in the immediate kitchen area and adjacent front-of-house. However, the producers’ plan was to have a kitchen that was actually functional, which presented a few problems. To begin with, actors would be shuttling skillets, pots & pans, utensils, and plates all over the set. Secondly, commercial stoves and ovens were operating in the scenes. Ventilation exhaust fans had to be working, which is essentially the equivalent of a Pratt & Whitney turbojet engine running three feet above the actors. And then there was all the shiny stainless steel surrounding the entire set, with practical lighting to boot. A boom operator’s nightmare…

Of course, wireless mics don’t work too well in an environment that blocks RF, not to mention all the multipath issues caused by RF bouncing off multiple steel surfaces. Additionally, the decision had been made to use much of the existing practical kitchen lighting (all on SCR dimmers), which further trashed what little RF bandwidth we had left to operate in (Note: Chicago is an RF hellhole).

So, armed with nothing more than a stack of wireless mics, a seasoned Boom Operator (Jason Johnston) and a prayer, we jumped in. Thankfully, when the show was cut, the editors managed to avoid the worst of the problems that plagued us. That, along with some masterful work by Dialogue Editor Evan Benjamin and Re-recording Mixer Steve “Major” Giammaria, led to a finely honed pilot.

wide shot

underside

Season 1

The world of television pilots is a fickle one. Dozens of TV pilots are pitched to the networks every season, but most never go before the cameras. Of the few that do, fewer still get green-lit for a full season. I had no reason to think that a show involving a restaurant and feuding cousins would ignite much interest on the part of the viewers.

So, I was surprised to receive another call from the same unit manager in November of 2021, asking if I would be interested in doing a full season of the show. Having already experienced the pitfalls of the pilot, I was a bit more wary when it came to doing a full season. Where would we be shooting? Was it going to be all practical sets again? How many cameras? How many actors? The only firm answer was in regard to the restaurant set, which is based in part on an actual sandwich shop called Mr. Beef, located in the River North section of Chicago. I was assured this would be built as a stage set at Cinespace Studios in Chicago. What wasn’t mentioned was that it would be an exact replica of the restaurant itself. Same kitchen, front entry area, same counter, same practical lights, and same working neon signs.

In other words, the show set would present identical constraints and issues we had encountered during the pilot. The only major concession was that the exhaust fan required for stove ventilation would be moved to the roof area of the stage but would not be a variable speed fan. With the cooperation of the SFX department, however, we were able to convince the powers-that-be to install a system which was higher air intake and lower in velocity than what would typically be used in a commercial kitchen. While not completely silent, it did at least reduce the noise to a level that was manageable for many scenes.

What we didn’t anticipate was the plan to shoot one episode (EP 7 “Review”) in a single continuous 18-minute take, which contained multiple complications for every department. Thanks to some incredible boom work on the part of my crew, we made it through, with virtually no ADR.

RF Constraints

Like some other major metropolitan areas in the post-repack era, Chicago is a nightmare when it comes to the UHF spectrum. When looking at the region in its entirety, the band from 470mHz up to 604mHz is occupied by UHF TV channels with a signal strength that varies from lakefront to the suburbs. The only band left is a small slice of 470mHz, which at best will allow about eight channels of wireless, depending on modulation. Further, when working on the stages, we share the spectrum with three other shows shooting in the same stage building, making RF coordination a real challenge.

To overcome these obstacles, we move whatever non-critical systems (IFB’s, coms, etc.) we can to frequencies which won’t cause intermod issues with the primary talent and boom wires. We employ both digital and analog systems, so it’s crucial to keep on top of differences in modulation schemes.

When moving to various locations around the city and suburbs, wireless assignments need to be changed to accommodate the spectrum available, so it’s not unusual to have to re-tune a dozen or more channels of wireless to avoid problems in a given geographic area.

In addition to RF spectrum issues, there were complications caused by the stage lighting system controllers, along with two neon signs, part of the design at the original location used for the show. The signs were a frequent source of wideband RF noise and EMI. Despite attempts at reducing the noise caused by the high-voltage transformer, it was virtually impossible to contain the RF spray generated by the signs themselves. In situations where the signs needed to be left on, iZotope was our friend. To aid the post crew in working around these issues, we recorded samples of just the interference (minus any set noise), providing a clean signature track that could hopefully be used to cancel the interference in the actual dialog tracks.

Season 2

When it was announced that the show would be picked up for a second season, this gave us the opportunity to address a few of the issues that had plagued us during Season 1. This included a better multiple-antenna RF system, installed in and around the stage set, which aided us in covering scenes that moved from the kitchen to front-of-house and back again. We were also able to arrange for the electrical department to set up a separate set of controls for all the refrigeration equipment on set, which is frequently used to store actual prop food during shooting. All the food seen on the show is edible; its preparation is supervised by the Showrunner’s sister, Coco Storer, whose experience working in high-end kitchens inspires some of the storylines.

We were also able to finesse the placement of mics on some of the talent, mostly to accommodate both aprons and “street clothing” costumes. In a few instances, mics were placed in the actors’ hair to avoid situations where the mics might be completely blocked.

Episode 1 of Season 2 starts off with a bang (literally), as the staff of “The Original Beef” take hammers and crowbars to the set. Yes, they are actually doing the real demolition of the set, which we initially thought would be filmed as an insert shot separate from the dialog. Another surprise…

And, as in the first season, the finale of Season 2 features yet another continuous take which takes us from the kitchen to the front-of-house, and back again. The episode ends with Carmy being accidentally locked in the walk-in refrigerator on opening night of the restaurant.

Season 3

Season 3 of the show (“Tomorrow”) as aired, is a montage set to music which serves as a recap of Carmy’s life up until now. Primarily backed by a needle-drop music track, interspersed with snippets of dialog, we track Carmy’s torturous beginnings during his apprenticeship at the French Laundry restaurant, up until the present-day realities of a kitchen cleanup. Overall, this season is much quieter than the two previous seasons.

Befitting the general emotional tone of the season, there are also scenes filmed at a Michelin-starred Chicago restaurant (“Ever”), operated by Chef Curtis Duffy. This restaurant incorporates some of the best sound treatment I’ve ever encountered for a front-of-house dining area. With absolutely nothing that would clue the average diner as to how the room was treated, I had to look very carefully at the walls and ceiling areas to figure out how the architect and builders had treated the surfaces. At the end, I remarked to Chef Duffy, “I would eat here based on the acoustics alone, even if the food was terrible.” I wish every location where we shoot could be as good as that one.

Season 3 ends with a farewell dinner, marking the closing of Ever, where Carmy is reunited with his former colleagues, along with the hateful chef (David Fields) who we’ve seen previously. The episode ends as a cliffhanger, with many unresolved questions facing Carmy, including whether the restaurant will survive.

Most problematic from a sound standpoint was Episode 3 (“Doors”), which featured a number of scenes that were guaranteed to ignite PTSD for anyone who has ever worked in a restaurant. Dishes stacked up in the sink, orders gone wrong, someone’s hand being cut with a utility knife, shouting matches and physical altercations. With frequent overlapping dialog, this episode was guaranteed to have the Dialogue Editor order up a 100-tablet bottle of Xanax.

Season 4

Season 4 of The Bear opens with an episode (“Groundhog”) similar in tone to that of Season 3, with a flashback sequence that takes us to Carmy’s time with his brother, Mikey. Subsequently, we see snippets of The Chicago Tribune restaurant review that ended Season 3, which leads to a lot of soul-searching on the part of Carmy and the staff.

The generally quiet and introspective tone of the season doesn’t last for long, however.

16 Actors Under a Table? No Problem…

One particularly challenging scene for sound takes place in Episode 7 of the season. This episode revolves around a reception for the wedding of Richie’s ex-wife, Tiffany, to her new beau, Frank. It also features nearly every member of the Berzatto family. Predictably, this results in some moments of high drama. Midway through the episode, we see Richie and Tiffany’s young daughter crawling underneath a huge table of food and drink, in an attempt to escape the impending “stepfather-daughter” dance with Frank. Richie soon follows and does his best to assuage her fears. Before long, most of the Berzatto family and a few other guests are under the table in a free-for-all group therapy session focused on the fears of each of the characters.

The scene presented unique hurdles for the Sound Department. While we could employ the usual approach of slapping a lav mic on each of the actors, we knew that the actors would be jostling around under the table, crouched over, with wardrobe selections that were sure to be the enemy of good sound. And while we might be able to get a boom mic underneath the actors on close-ups, wide shots would show the entire floor and underside of the table. There were no easy options here.

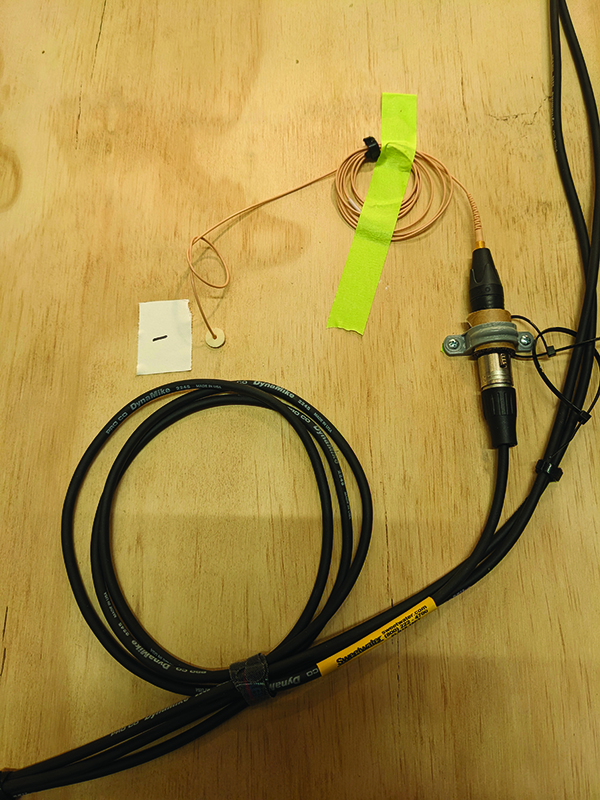

The only solution was to figure out a way to employ mics hidden on the underside of the table, which was composed of ¾ inch plywood, and aged down with a light faux stain finish. The standard approach of PZM mics attached under the surface was going to be a non-starter, even if they were recessed to be flush with the underside of the table. In addition, there was the issue of actors and objects bumping into the table, which would be transmitted into the plywood and subsequently picked up by the mics. Hardly an ideal scenario for dialog recording.

After considering all the options, the only approach that seemed workable was to employ small mics embedded in the underside of the table. Fortunately, for the scenes that took place with the actors under the table, the tabletop itself would not be seen on camera (Insider scoop: The tabletop shown in the reception scenes was a second table laden with the usual food and drink set dressing).

The next problem was to figure out how to hide the mics from camera view, as well as isolating them from any vibration that might be induced from the plywood surface. The most straightforward approach was to drill holes in the table surface and insert small diameter lavalier mics with foam to isolate them from the plywood. The art department was not particularly enthralled with this approach, but after we assembled a mock-up of the table with mics and foam in place, and aged to match the wood surface, they relented.

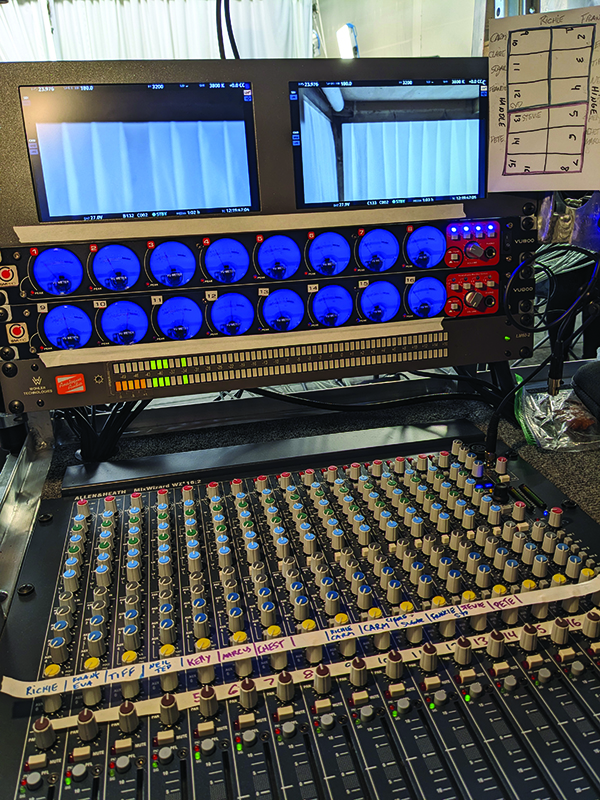

So, now we had sixteen more mics to deal with, in addition to lav mics on the actors and a boom mic. Since the actors would move around during the scene, we only had a rough idea of what mic(s) might pick up their dialog for any given part of the scene. The only answer for this was an additional 16-channel mixer, with a separate mix track consisting of just the zone mics for the Picture Editors to work with.

In the end, we maxed the channel capabilities on the Sound Devices Scorpio recorder that we employ for most of our stage work, with all the mics isolated, and two mix tracks. Needless to say, the Dialogue Editor (Evan Benjamin) was rather astonished when he received thirty-two channels, which was well in excess of even the most complicated scenes we had done to date. Soundminer was his friend in helping to sort out all the tracks, along with a plot of the table showing mic positions as a roadmap.

One Actor, Five Mics

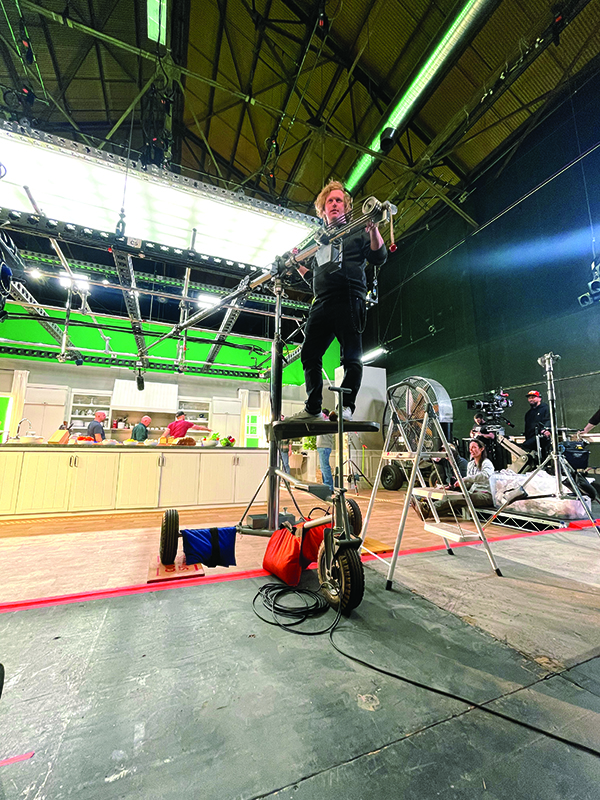

This was not to be the end of pain for Season 4, however. Next up was Episode 8 (“Green”), which includes a mysterious dream sequence with Sydney acting as the chipper host of a cooking show that quickly takes a turn into a kitchen nightmare. This includes wind and water flooding the set, cabinets banging open and shut, and general mayhem, all of which were actual on-set effects, as opposed to CGI. Given the improvisational nature of the dialog, the goal was to get as useable a track as possible.

It’s not easy to overcome the noise from a Ritter fan six feet away from set, combined with rain FX, hydraulics, and other assorted noise. But since the set was portrayed as a TV cooking show set, we were able to convince the director that a studio mic boom would be something that would typically be found in this scenario. Consequently, we had the advantage of using a Fisher boom AND include it as part of the set dressing. However, as this was to be a one-take shot, we didn’t want to risk it to a single mic. So, in addition to a Sennheiser MKH-415 on a Fisher Model 2, we also had a mic on the actress, two mics rigged above the table, and a mic hidden in the tabletop. Somehow, the post sound crew was able to extract something usable from all these sources, without resorting to ADR.

The Bear is definitely not your typical run-of-the mill episodic TV show. Major challenges for both the production and post-production sound team are routine.

Many thanks to my crew for some stellar work over the run of the show.

Joe Campbell – Boom Operator

Michael Capulli – Boom Operator

Nicholas Price – Utility

Sharon Frye – Utility

Eric LaCour – Utility

Nick Ray Harris – Boom and Additional Mixer

Uriah Brown – Utility

Nick Fabellai – Utility

Blake Scheller – Utility

Mikey Wilson – Utility

Tim Edson – Utility

Jason Johnston – Boom (Pilot)

Carly Perkins – Utility (Pilot)